Evidence for a further projection in transitive verb phrases

The account of the syntax of ECM subjects provides a way of capturing the intuition (defended in Postal 1974 and Lasnik and Saito 1991) that the subject of an ECM infinitive raises to become the object of the ECM verb. The raised subject the witness in (102)–(105) becomes the highest constituent within the inner VP core in which the ECM verb prove originates (as in L´opez 2001); and since direct objects are the highest internal arguments within VP, this amounts to claiming that the infinitive subject is raised up to become the direct object of the verb prove.

However, some of the assumptions underlying this analysis seem questionable. For example, the assumption that a lexical verb like prove can have an [EPP] feature which triggers raising of the subject of its infinitive complement to become an internal argument of prove seems problematic from three standpoints. Firstly, [EPP] is a feature canonically associated with functional categories like T and C, and not with substantive (lexical) categories like V. Secondly, an internal argument of a verb is theta-marked by the verb, and yet the raised nominal the witness in a structure like (105) is not theta-marked by the ECM verb prove (but rather is a thematic argument of the verb lied). Thirdly, the verb prove starts out as a predicate with a single internal argument (a clausal complement), but ends up with two internal arguments – an accusative object and a clausal complement. This violates the Projection Principle suggested in earlier work by Chomsky (1981, p. 29) – a principle which requires that the properties of lexical items (including the kinds of arguments they permit) should remain constant throughout the derivation.

A further questionable aspect of the ECM analysis is the assumption that adverbs adjoin to intermediate projections. This is problematic in two respects. Firstly, other grammatical operations like movement seem ‘blind’ to intermediate projections, so that no intermediate projection can be a goal for movement (in the sense that no intermediate projection can undergo movement) or a target for movement (in the sense that no movement operation adjoins a moved constituent to an intermediate projection): on the contrary, only a head or a maximal projection can be a goal or target for movement. If movement cannot involve intermediate projections, we might assume that adjunction cannot either. Moreover, the assumption that adverbs can adjoin to intermediate projections seems to conflict with a principle suggested by Chomsky (1998, p. 49) to the effect that the selectional properties of a head must be satisfied before any other constituent can be introduced into the projection containing the head. Since a head selects its arguments, this suggests that a head must merge with its arguments before any material can be adjoined to the relevant projection – or in simpler terms, it suggests that adverbs can adjoin only to maximal projections, and not to intermediate projections. But if this is so, an analysis of ECM structures like that in (105) is untenable, because it presupposes that an adverb like conclusively can be adjoined to an intermediate V-bar projection of the verb prove.

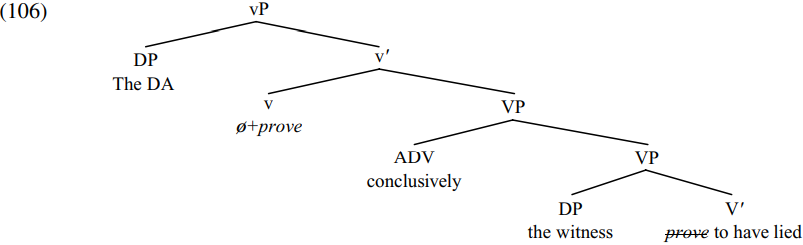

However, the dilemma we face is that if we suppose that adverbs like conclusively adjoin only to maximal projections like VP, it follows that conclusively must adjoin to the VP in (105), so that in place of (105) we will have the structure shown in simplified form in (106) below:

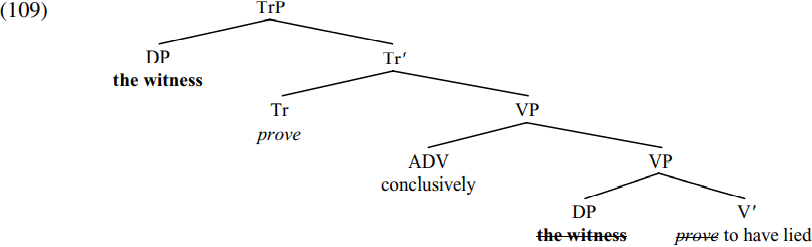

The twin problems posed by a structure like (106) are that on the one hand it wrongly predicts that (107a) below is grammatical, and that on the other it wrongly predicts that (107b) is ungrammatical:

How can we get round this problem without abandoning the claim that adverbs adjoin to maximal (and not intermediate) projections?

A solution advocated in Koizumi (1993, 1995) is to suppose that transitive verb phrases can be split into three projections rather than (as we have assumed so far) two, with an additional AgrOP (Object Agreement Projection) positioned between VP and vP. Work in the same era (dating back to Pollock 1989) similarly supposed that TP could be split into separate TP and AgrSP (Subject Agreement Projection) constituents: see Radford (1997a) for discussion of earlier work on Agr projections in English. However, after surveying the evidence for positing projections of abstract Agr(eement) heads, Chomsky (1995, p. 377) concludes that ‘It seems reasonable to conjecture that Agr does not exist.’ One objection which he voices to Agr heads is that they cannot be assigned any interpretation at the semantics interface, and hence will cause the derivation to crash.

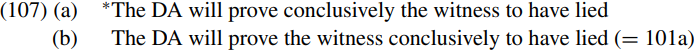

Mindful of Chomsky’s objections, Bowers (2002) proposes an alternative triple-projection account of the structure of transitive clauses in which located between vP and VP is a projection of a functional head which encodes an interpretable Transitivity property: he labels this head Tr, and assumes that it projects into a TrP ‘Transitivity Phrase’. Bowers further supposes that Tr carries a set of (object-agreement)  -features, and that it also has an [EPP] feature. On this view, (107b) will be derived as follows. The derivation proceeds in familiar ways until we reach the stage where the verb prove merges with its TP complement the witness to have lied to form the VP prove the witness to have lied. The adverb conclusively is then adjoined to this VP, expanding it into an even larger VP constituent. The resulting VP is then merged with a Tr(ansitivity) head which carries an interpretable transitivity feature (below shown crudely as [+Trans]), together with uninterpretable person/number/EPP features, so deriving (108) below:

-features, and that it also has an [EPP] feature. On this view, (107b) will be derived as follows. The derivation proceeds in familiar ways until we reach the stage where the verb prove merges with its TP complement the witness to have lied to form the VP prove the witness to have lied. The adverb conclusively is then adjoined to this VP, expanding it into an even larger VP constituent. The resulting VP is then merged with a Tr(ansitivity) head which carries an interpretable transitivity feature (below shown crudely as [+Trans]), together with uninterpretable person/number/EPP features, so deriving (108) below:

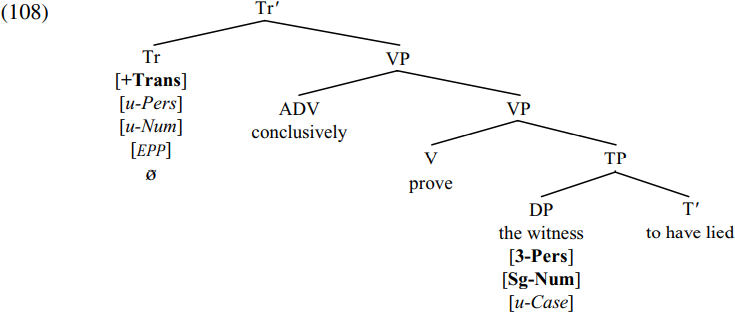

The Tr head is strong, and so triggers raising of the verb prove from V to Tr. Tr is also active for agreement and case-marking by virtue of its uninterpretable person/number features, and so probes and locates the witness as the only active goal within its domain. Agreement between the two leads to valuation of the person/number features of Tr and to valuation of the case feature of the witness as accusative; the uninterpretable features on probe and goal are also deleted once valued, since both probe and goal are  -complete. (An interesting possibility which we will not explore further here is that accusative case is in fact an uninterpretable transitivity feature which is valued by the transitivity feature on Tr – in much the same way as nominative case may be an uninterpretable tense feature which is valued by the interpretable tense feature on T) Since Tr has an [EPP] feature, it triggers raising of the witness to spec-TrP (thereby deleting its [EPP] feature), so deriving the structure shown in simplified form in (109) below:

-complete. (An interesting possibility which we will not explore further here is that accusative case is in fact an uninterpretable transitivity feature which is valued by the transitivity feature on Tr – in much the same way as nominative case may be an uninterpretable tense feature which is valued by the interpretable tense feature on T) Since Tr has an [EPP] feature, it triggers raising of the witness to spec-TrP (thereby deleting its [EPP] feature), so deriving the structure shown in simplified form in (109) below:

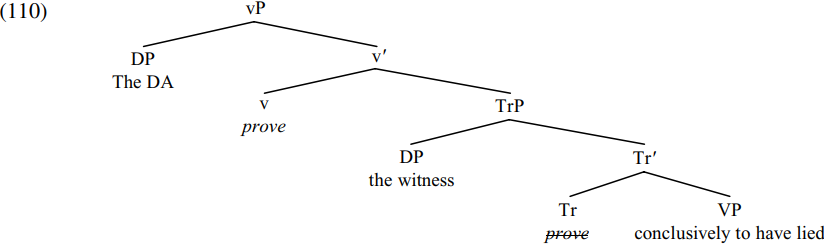

The resulting TrP is then merged with an agentive light verb (whose external argument is the AGENT the DA). The light verb is strong, so triggers raising of the verb prove from Tr to v, thereby forming the vP shown in simplified form below:

The derivation then continues in familiar ways, ultimately deriving (107b) The DA will prove the witness conclusively to have lied. This revised analysis of ECM structures is consistent with the twin assumptions that (i) adverbs adjoin only to maximal projections, and (ii) only functional heads (like Tr, T and C) can have an [EPP] feature.

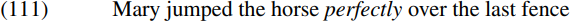

However, these twin assumptions require us to rethink our earlier vP/VP analysis of simple transitive clauses. To see why, consider sentence (47a) above, repeated below:

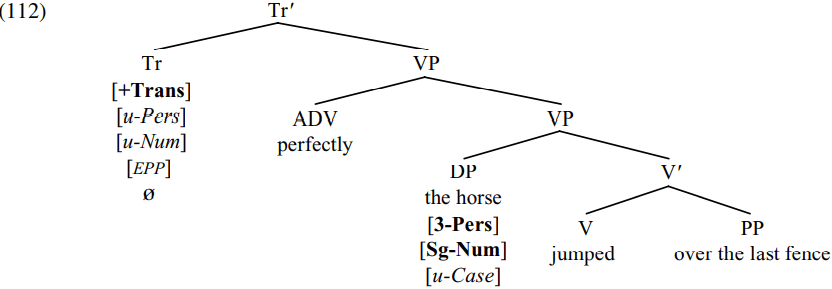

In the light of our revised assumptions, this will now be derived as follows. The verb jumped merges with its complement over the last fence and its specifier the horse to form the VP the horse jumped over the last fence. The VP-adverb perfectly adjoins to this VP, so forming the even larger VP perfectly the horse jumped over the last fence. The resulting VP is then merged with a Tr(ansitivity) head which carries an interpretable transitivity feature, uninterpretable person/number  -features and an interpretable [EPP] feature, so forming the structure shown in simplified form below:

-features and an interpretable [EPP] feature, so forming the structure shown in simplified form below:

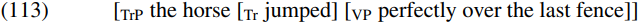

The Tr head is strong, and consequently triggers raising of the verb jumped from V to Tr. Agreement between the Tr head and the DP the horse values (and deletes) the person/number features of Tr and values (as accusative) and deletes the case feature of the horse. The [EPP] feature of Tr triggers movement of the horse to spec-TrP, so deriving the overt structure shown in skeletal form in (113) below:

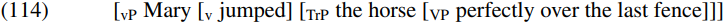

The resulting TrP is then merged with an agentive light verb (whose external argument is the AGENT Mary). The light verb is strong, so triggers raising of the verb jumped from Tr to v, thereby forming the overt structure shown in highly simplified form below:

The resulting vP will then be merged with a past-tense T constituent, with Mary raising to spec-TP. Merging the resulting TP with a null declarative complementizer will derive the syntactic structure associated with (111) Mary jumped the horse perfectly over the last fence.

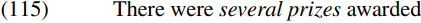

If we follow Bowers (2002) in supposing that passive VPs also contain a TrP projection, we can offer an interesting account of the position of the italicized indefinite nominal in passives such as:

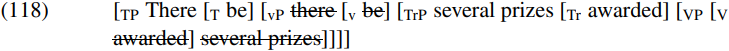

The (passive) verb award(ed) merges with its complement several prizes to form the VP awarded several prizes. This VP merges with a Tr head which (by virtue of being strong) triggers movement of the verb awarded from V to Tr and (by virtue of its [EPP] feature) triggers raising of the complement several prizes to become the specifier of the transitivity head Tr, so deriving the structure shown in skeletal form below:

This is then merged with a light verb containing the passive auxiliary be. Since be is a non-thematic verb which projects no external argument, expletive there can be merged in spec-vP, so deriving:

The resulting vP is then merged with a finite T constituent which agrees with both there and several prizes (assigning nominative case to the latter), triggers raising of be from v to T, and also triggers raising of there from spec-vP to spec-TP, so ultimately deriving:

The resulting TP is then merged with a null declarative complementizer, and BE is spelled out as were in the PF component. (See Chomsky 1999 for an alternative account of sentences like (115) in which the preverbal position of several prizes is claimed to be the result of a PF movement process.)

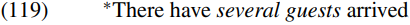

While passives like (115) allow the complement to be positioned preverbally, unaccusatives do not – as we see from the ungrammaticality of:

One way of accounting for this contrast is to suppose (following Bowers 2002) that passive verb phrases are vP+TrP+VP structures which contain a TrP projection which can house a preposed complement, whereas unaccusative verb phrases are simple vP+VP structures which (by virtue of lacking TrP) contain no landing site for a preposed complement.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة