Transitive light verbs and accusative case assignment

We saw that nominative and null case are assigned to a goal by a matching  -complete probe (the probe being a finite T for nominative case, and a non-finite control T for null case); however, we had nothing to say about accusative case assignment. If UG principles determine that all structural case assignment involves assignment of case to a goal by a

-complete probe (the probe being a finite T for nominative case, and a non-finite control T for null case); however, we had nothing to say about accusative case assignment. If UG principles determine that all structural case assignment involves assignment of case to a goal by a  -complete matching probe, we can hypothesize that accusative case is likewise assigned to a goal by a

-complete matching probe, we can hypothesize that accusative case is likewise assigned to a goal by a  -complete probe which matches the goal in respect of its person and number features. But what could be the probe responsible for assignment of accusative case to (say) the accusative complement them in a transitive sentence such as that below?

-complete probe which matches the goal in respect of its person and number features. But what could be the probe responsible for assignment of accusative case to (say) the accusative complement them in a transitive sentence such as that below?

Chomsky in recent work has suggested an answer along the lines of (92) below:

Let’s further suppose that:

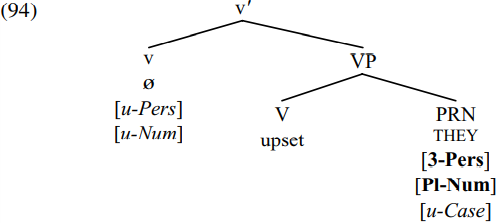

In the light of (92) and (93), consider how the derivation of (91) proceeds.

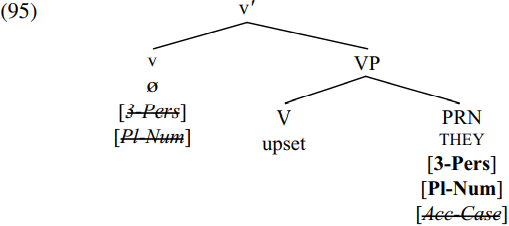

The verb upset is merged with its complement THEY to form the VP upset THEY (capital letters being used to denote an abstract lexical item whose precise phonetic spellout as they/them/their has not yet been determined): the pronoun carries interpretable third-person, plural-number features and an uninterpretable (and unvalued) case feature. The resulting VP is then merged with a null transitive light verb which (since case assignment requires probe and goal to match in  -features) will carry unvalued and uninterpretable person/number features, so forming the v-bar below (with interpretable features shown in bold and uninterpretable features in italics):

-features) will carry unvalued and uninterpretable person/number features, so forming the v-bar below (with interpretable features shown in bold and uninterpretable features in italics):

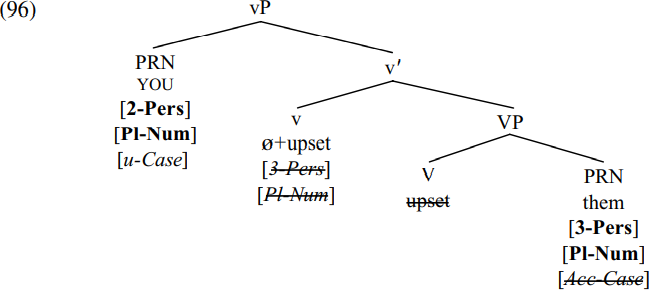

The null light verb probes and identifies THEY as the only active goal which carries an uninterpretable case feature. The goal THEY values (and, being  - complete, deletes) the person/number

- complete, deletes) the person/number  -features of the light-verb probe (these will ultimately have a null spellout, like the light verb itself). Conversely, the transitive light verb values the unvalued case feature of THEY as accusative in accordance with (92) (so that THEY is ultimately spelled out as them) and (by virtue of being

-features of the light-verb probe (these will ultimately have a null spellout, like the light verb itself). Conversely, the transitive light verb values the unvalued case feature of THEY as accusative in accordance with (92) (so that THEY is ultimately spelled out as them) and (by virtue of being  -complete) deletes it, so deriving:

-complete) deletes it, so deriving:

The null light verb is affixal, and so will trigger raising of the verb upset from V to v. Since the (causative) light verb in (95) is transitive, it projects an AGENT external argument. The relevant external argument is YOU in (91), and (if it refers to more than one individual) this enters the derivation with interpretable second-person and plural-number features, but an unvalued case-feature, so forming the vP (96) below:

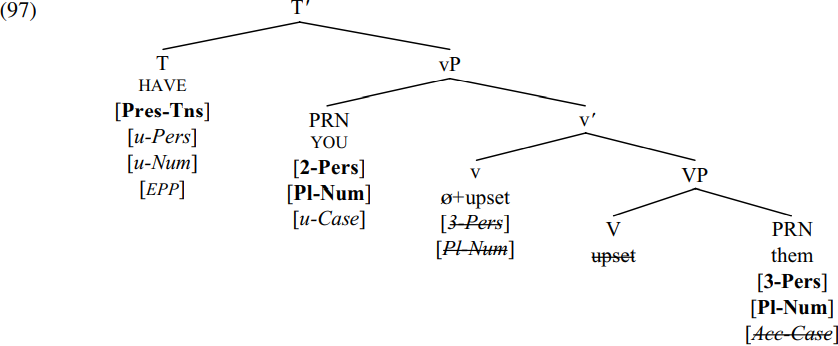

The vP thereby formed is merged with a null finite T containing the perfect auxiliary HAVE, which has an interpretable present-tense feature, uninterpretable (and unvalued)  -features, and an uninterpretable [EPP] feature. Merging T with its vP complement derives:

-features, and an uninterpretable [EPP] feature. Merging T with its vP complement derives:

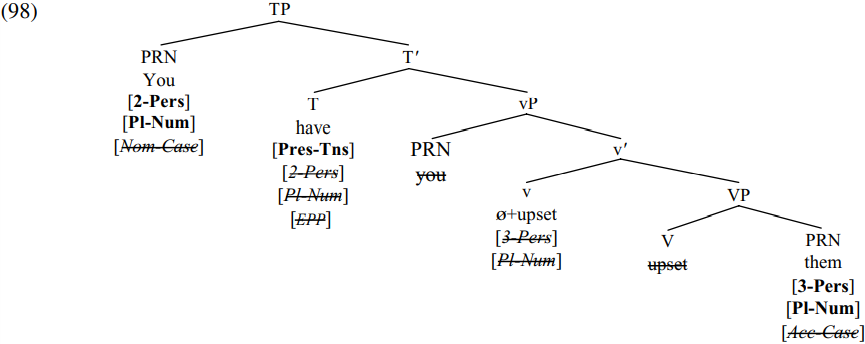

[T HAVE] then probes and locates the pronoun YOU as the only active goal with an unvalued case feature which it c-commands. This results in the pronoun valuing and deleting the person/number features of the auxiliary, and conversely in the auxiliary valuing the case feature of the pronoun as nominative, and deleting it: hence the items HAVE and YOU are spelled out as HAVE and YOU at PF. The [EPP] feature of T triggers raising of the pronoun you from spec-vP to spec-TP (thereby deleting the [EPP] feature on T), deriving the structure (98) below:

The resulting structure is then merged with a null declarative complementizer to derive the CP structure associated with (91) You have upset them. (On accusative case assignment in double-object structures like give someone something, see Goodall 1999.)

An interesting question arising from the assumption that the objects of transitive verbs are assigned accusative case by a light verb which projects an external argument is whether this analysis can be extended to the case-marking of (italicized) accusative subjects of the (bracketed) infinitival TPs in ECM/Exceptional Case-Marking structures like those below:

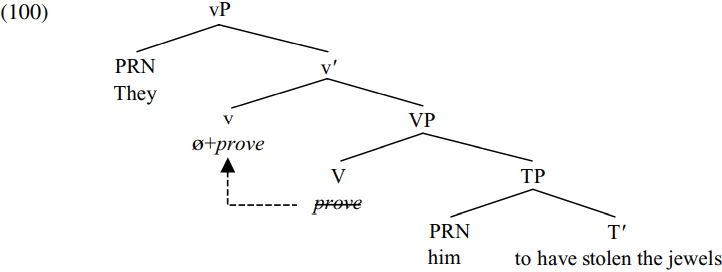

At first sight, the answer would appear to be straightforward. After all, if the italicized subject occupies spec-TP position within the bracketed TP complement, and if the bold-printed ECM verb originates as the head of a VP which is the complement of a transitive light verb and subsequently raises to adjoin to the light verb (in the manner shown by the dotted arrow below), (99a) will have the structure shown in (100) below at the end of the main-clause vP cycle (simplified by not showing the internal structure of T-bar):

Since the light verb ø which occupies the head v position within vP is transitive (by virtue of having an external argument, namely they), and since it c-commands the infinitive subject him, it can assign accusative case to him with concomitant  -feature matching (i.e. the light verb will contain unvalued person and number features which are valued by those of him; like the light verb itself, these will ultimately have a null phonetic spellout).

-feature matching (i.e. the light verb will contain unvalued person and number features which are valued by those of him; like the light verb itself, these will ultimately have a null phonetic spellout).

However, an important question raised by the above analysis is how we account for the position of the italicized adverbial and prepositional expressions in ECM structures such as the following:

In sentences like (101), the italicized adverbial/prepositional expression is positioned inside the bracketed infinitive complement, and yet is construed as modifying the (bold-printed) transitive verb which lies outside the bracketed complement clause. How can we account for this seeming paradox? To make our discussion more concrete, let’s consider how to derive (101a).

If we assume that the adverb conclusively (by virtue of modifying the verb prove) originates as an adjunct to the V-bar headed by prove, the problem we face is accounting for how both the verb prove and the DP the witness end up in front of the adverb conclusively. Movement of the verb prove in front of conclusively is no problem if we suppose that verbs move from the head V position in VP to adjoin to a null light verb, and thereby come to occupy the head v position of vP. But how does the infinitival subject the witness come to be positioned above the adverb conclusively, but below the verb prove?

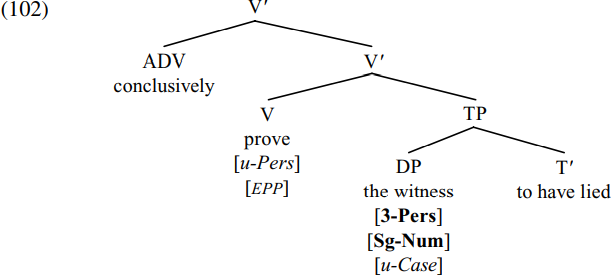

One possibility is that an ECM verb like prove (like infinitival to in raising structures) has an [EPP] feature and an unvalued person feature which together require the closest matching nominal expression which they c-command to be moved to the outer edge of VP. Given this assumption, the relevant part of the derivation of (101a) will proceed as follows. The verb prove merges with the infinitival TP the witness to have lied (whose structure we ignore here, in order to simplify exposition) to form the V-bar prove the witness to have lied, and the adverb conclusively merges with this V-bar to form the even larger V-bar conclusively prove the witness to have lied. Let’s suppose that the witness has valued (third-)person and (singular-)number features, and an unvalued and uninterpretable case feature, so that at this stage we have formed the V-bar shown in simplified form below:

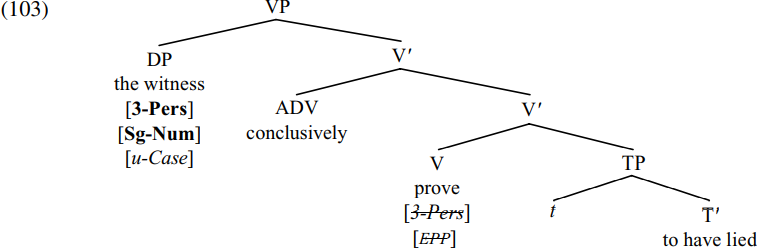

The uninterpretable person feature on the verb prove serves as a probe which picks out the closest active goal with a matching person feature, locating the DP the witness, which is active by virtue of its uninterpretable case feature: since the DP the witness is  -complete, it values and deletes the person feature on the verb prove. The [EPP] feature of prove triggers movement of the witness to the outer edge of the relevant V-projection (and is thereafter deleted), so that the witness becomes the specifier of the V-bar in (102), forming the VP (103) below:

-complete, it values and deletes the person feature on the verb prove. The [EPP] feature of prove triggers movement of the witness to the outer edge of the relevant V-projection (and is thereafter deleted), so that the witness becomes the specifier of the V-bar in (102), forming the VP (103) below:

Because the verb prove is not  -complete (by virtue of carrying only person and not number), it does not value or delete the case feature on the DP the witness, so that the latter remains active.

-complete (by virtue of carrying only person and not number), it does not value or delete the case feature on the DP the witness, so that the latter remains active.

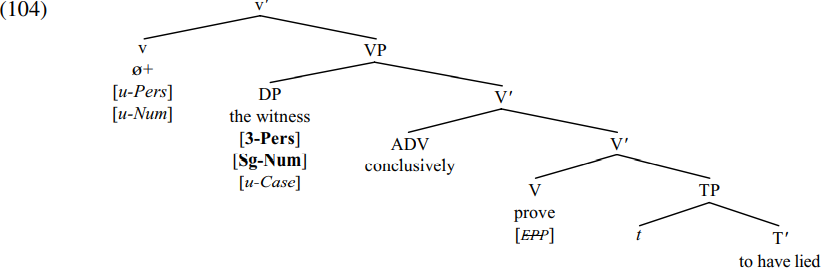

The VP in (103) is then merged as the complement of a null (affixal) light-verb. The light verb is transitive (since it has the external argument the DA), and transitive light verbs carry a complete set of unvalued  -features, so that merging the relevant light verb with (103) above will form (104) below:

-features, so that merging the relevant light verb with (103) above will form (104) below:

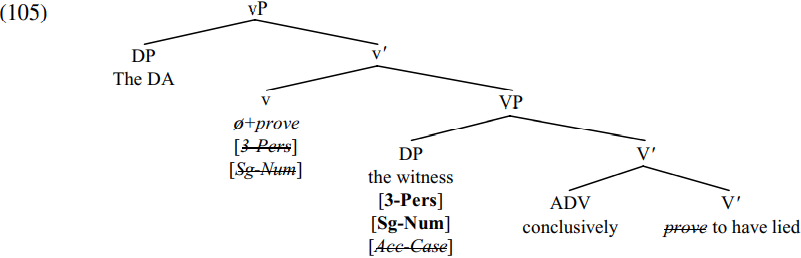

At this point, the light verb (active by virtue of its uninterpretable  -features) serves as a probe and searches for an active matching nominal goal which it c-commands, locating the witness (which is active by virtue of its uninterpretable case feature). The light verb values the unvalued case feature of the witness as accusative in accordance with (92), and deletes it. The DP the witness in turn values and deletes the unvalued person and number features of the light verb. Since the light verb is affixal in nature (indicated by the + sign in ø+), it triggers raising of the verb prove to adjoin to the light verb. Since the light verb is transitive, it also projects an external argument (in this case, the DA) in spec-vP. Thus, at the end of the vP cycle, we have the structure shown in (105) below (simplified by showing only features of the light verb ø and the DP the witness, and by omitting a number of traces and other empty categories):

-features) serves as a probe and searches for an active matching nominal goal which it c-commands, locating the witness (which is active by virtue of its uninterpretable case feature). The light verb values the unvalued case feature of the witness as accusative in accordance with (92), and deletes it. The DP the witness in turn values and deletes the unvalued person and number features of the light verb. Since the light verb is affixal in nature (indicated by the + sign in ø+), it triggers raising of the verb prove to adjoin to the light verb. Since the light verb is transitive, it also projects an external argument (in this case, the DA) in spec-vP. Thus, at the end of the vP cycle, we have the structure shown in (105) below (simplified by showing only features of the light verb ø and the DP the witness, and by omitting a number of traces and other empty categories):

Subsequently, the resulting vP is merged as the complement of [T will], which serves as a probe valuing (as nominative) and deleting the uninterpretable case feature on the DA (not shown here); the [EPP] feature and unvalued person/number features of will trigger movement of the DA to become the specifier of the TP headed by will. Merging the resulting TP with a null declarative complementizer derives the structure associated with (101a) The DA will prove the witness conclusively to have lied.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة