VP shells in resultative, double-object and object-control structures

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

344-9

الجزء والصفحة:

344-9

2023-02-04

2023-02-04

2400

2400

VP shells in resultative, double-object and object-control structures

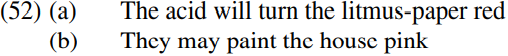

The VP shell analysis outlined above can be extended from predicates like load which have both nominal and prepositional complements to so-called resultative predicates which have both nominal and adjectival complements – i.e. to structures such as those below:

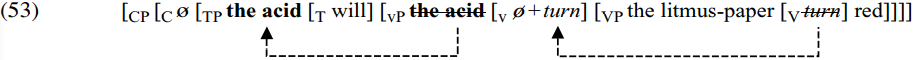

In (52a), the verb turn originates in the head V position of VP, with the DP the litmus-paper as its subject and the adjective red as its complement (precisely as in The litmus-paper will turn red); turn then raises to adjoin to a strong causative light verb ø heading vP; the subject of this light verb (the DP the acid) in turn raises from spec-vP to spec-TP, and the resulting TP merges with a null declarative complementizer – as shown informally in (53) below:

(For alternative analyses of resultative structures like (52), see Keyser and Roeper 1992; Carrier and Randall 1992; and Oya 2002.)

We can extend the vP shell analysis still further, to take in double-object structures. such as:

For example, we could suggest that (54a) has the structure (55) below (with arrows indicating movements which take place in the course of the derivation):

That is, get originates as the head V of VP (with the teacher as its subject and a present as its complement, much as in The teacher will get a present), and then raises up to adjoin to the strong causative light verb ø heading vP; the subject they in turn originates in spec-vP (and has the thematic role of AGENT argument of the null causative light verb ø), and subsequently raises to spec-TP. (For a range of alternative analyses of the double-object construction, see Larson 1988; 1990; Johnson 1991; Bowers 1993; and Pesetsky 1995.)

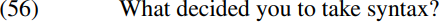

The VP shell analysis outlined above also provides us with an interesting solution to the problems posed by so-called object-control predicates. In this connection, consider the syntax of the infinitive structure in (56) below:

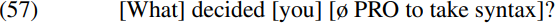

For reasons given below, decide functions as a three-place predicate in this use, taking what as its subject, you as its object, and the clause to take syntax as a further complement. If we suppose that the infinitive complement to take syntax has a PRO subject (and is a CP headed by a null complementiser ø), (56) will have the skeletal structure (57) below (simplified e.g. by ignoring traces: the three arguments of decide are bracketed):

Since PRO is controlled by the object you, the verb decide (in such uses) is an object-control predicate.

There are a number of reasons for thinking that the verb decide in sentences like (56) is indeed a three-place object-control predicate, and that you is the object of decide (rather than the subject of to take syntax). Thus, (56) can be paraphrased (albeit a little clumsily) as:

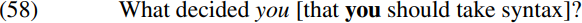

We can then say that you in (57) corresponds to the italicized object you in (58), and the PRO subject in (57) corresponds to the bold-printed you subject of the complement clause in (58). Moreover, the verb decide imposes pragmatic restrictions on the choice of expression following it (which must be a rational, mind-possessing entity – not an irrational, mindless entity like the exam):

This suggests that the relevant expression must be an argument of decide. Furthermore, the expression following decide cannot be an expletive pronoun such as there:

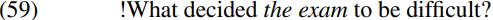

A plausible conclusion to draw from observations such as these is that the (pro)nominal following decide is an (object) argument of decide in sentences such as (56), and serves as the controller of a PRO subject in the following to infinitive. However, this means that decide has two complements in structures such as (56) – the pronoun you and the control infinitive to take syntax. Within a binary-branching framework, we clearly can’t assume that the V-bar headed by decide in (56) has a ternary-branching structure like:

However, we can avoid a structure like (61) if we suppose that (56) has a structure more akin to that of:

but differing from (62) in that in place of the overt causative verb make is an affixal causative light verb ø, with the verb decide raising to adjoin to the light verb as in (63) below:

The wh-pronoun what moves from spec-vP to spec-TP by A-movement, and then from spec-TP to spec-CP by A-bar movement. There is no T-to-C movement here for reasons which should be familiar (where we saw that questions with a wh-subject do not trigger auxiliary inversion). Instead, the past-tense affix (Tns) in T which carries person/number/tense features is lowered onto the light-verb complex ø+decide, which is ultimately spelled out as the past-tense form decided.

The light-verb analysis in (63) offers two main advantages over the analysis in (61). Firstly, (63) is consistent with the view that the merger operation by which phrases are formed is binary; and secondly, (63) enables us to attain a more unitary theory of control under which the controller of PRO is always a subject/specifier, never an object (since PRO in (63) is controlled by you, and you is the subject of the VP which was originally headed by the verb decide). This second result is a welcome one, since the verb decide clearly functions as a subject-control verb in structures such as:

where the PRO subject of to take syntax is controlled by the thematic subject of decided (i.e. by who).

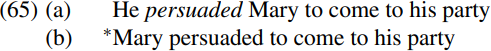

Although the verb decide can be used both as a so-called object-control predicate in sentences like What decided you to take syntax? and as a subject-control predicate in sentences like Who decided to take syntax?, most object-control predicates (like persuade) have no subject-control counterpart – as we see from (65) below:

This means that the analysis of sentences like (65a) will involve a greater level of abstraction, since it involves claiming that persuade originates in the head V position of VP and that Mary is the thematic subject of persuade (so that persuade originates in the same position as decide in (63) above, and Mary in the same position as you). We will also have to say that persuade is an obligatorily transitive affixal verb which must adjoin to the kind of abstract light verb which we find in structures like (63) – so accounting for the ungrammaticality of structures like (65b). (For further discussion of so-called object-control verbs, see Bowers 1993; for an analysis of the control verb promise, see Larson 1991.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة