Split CP: Finiteness projection

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

332-9

الجزء والصفحة:

332-9

1-2-2023

1-2-2023

2620

2620

Split CP: Finiteness projection

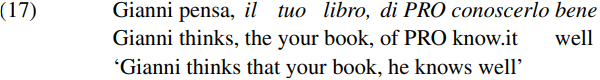

We argued that above TP there may be not just a single CP projection but rather at least three different types of projection – namely a Force Phrase, a Topic Phrase and a Focus Phrase (the latter two being found only in clauses containing focused or tropicalized constituents). However, Rizzi argues that below FocP (and above TP) there is a fourth functional projection which he terms FinP/Finiteness Phrase, whose head Fin constituent serves the function of marking a clause as finite or non-finite. He argues that Fin is the position occupied by prepositional particles like di ‘of’ which introduce infinitival control clauses in languages like Italian in structures such as (17) below:

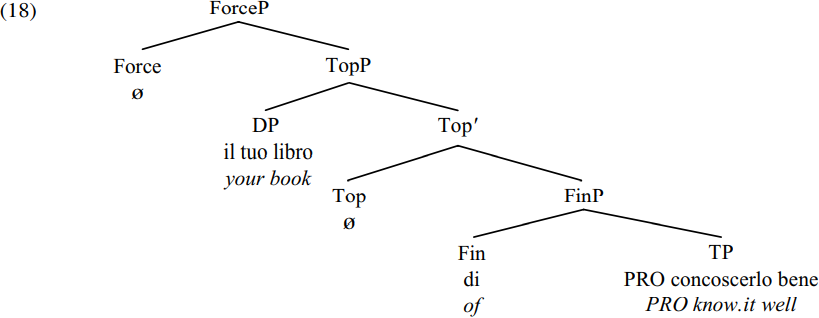

Rizzi maintains that the italicized clause which is the complement of pensa ‘thinks’ in (17) has the simplified structure (18) below:

Under his analysis, il tuo libro ‘the your book’ is a topic and di ‘of’ is a Fin head which marks its clause as non-finite (more specifically, as infinitival). Moreover, Rizzi maintains that the Fin head di ‘of’ assigns null case to the PRO subject of its clause (an account of null case assignment in keeping with our account, but not with the Chomskyan account given).

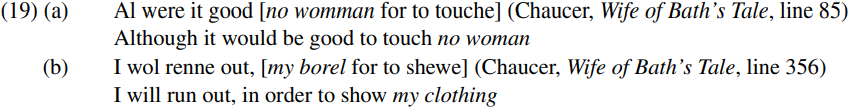

While present-day English has no overt counterpart of infinitival particles like Italian di in control clauses, it may be that for served essentially the same function in Middle English control infinitives such as those bracketed below:

In (19a,b) the italicized expression is the direct object of the verb at the end of the line, but has been focalized/tropicalized and thereby ends up positioned in front of for. This is consistent with the possibility that for occupies the same Fin position in Middle English as di in Modern Italian, and that the italicized complements in (19a,b) move into specifier position within a higher Focus Phrase/Topic Phrase projection. Since the for infinitive complement in (19) has a null subject rather than an overt accusative subject, we can suppose that it is intransitive in the relevant use.

In (19a,b) the italicized expression is the direct object of the verb at the end of the line, but has been focalized/tropicalized and thereby ends up positioned in front of for. This is consistent with the possibility that for occupies the same Fin position in Middle English as di in Modern Italian, and that the italicized complements in (19a,b) move into specifier position within a higher Focus Phrase/Topic Phrase projection. Since the for infinitive complement in (19) has a null subject rather than an overt accusative subject, we can suppose that it is intransitive in the relevant use.

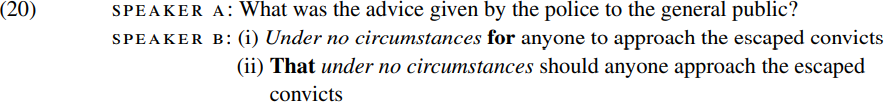

An interesting possibility raised by this analysis is that for in overt-subject infinitives in present-day English also functions as a non-finite Fin head – though an obligatorily transitive one. In this regard, consider the two different replies given by speaker B below:

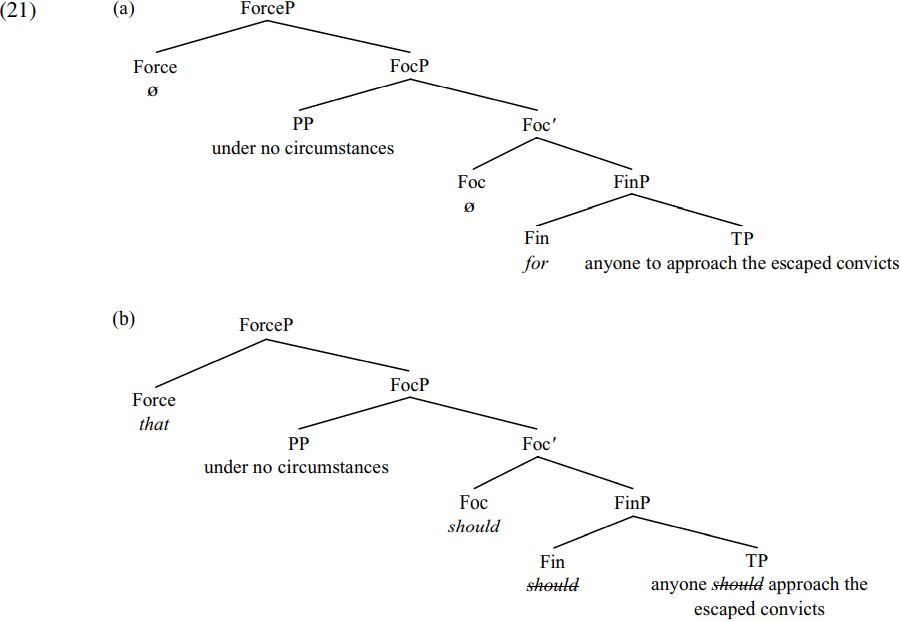

What is particularly interesting about speaker B’s replies in (20) is that the focused prepositional phrase under no circumstances precedes the complementizer for in (20Bi), but follows the complementizer that in (20Bii). This suggests that for occupies the head Fin position of FinP, but that occupies the head Force position of ForceP. On this view, the two answers given by speaker B would have the respective skeletal structures shown in (21a,b) below:

What is particularly interesting about speaker B’s replies in (20) is that the focused prepositional phrase under no circumstances precedes the complementizer for in (20Bi), but follows the complementizer that in (20Bii). This suggests that for occupies the head Fin position of FinP, but that occupies the head Force position of ForceP. On this view, the two answers given by speaker B would have the respective skeletal structures shown in (21a,b) below:

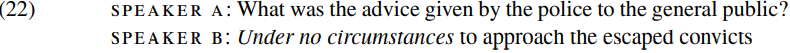

If Foc is a strong head in finite (though not infinitival) clauses, it follows that the auxiliary should in (21b) will raise from the head T position of TP into the head Foc position of FocP; and if we assume the Head Movement Constraint, it also follows that should must move first to Fin before moving into Foc. We can suppose that the reply given by speaker B in (22) below:

If Foc is a strong head in finite (though not infinitival) clauses, it follows that the auxiliary should in (21b) will raise from the head T position of TP into the head Foc position of FocP; and if we assume the Head Movement Constraint, it also follows that should must move first to Fin before moving into Foc. We can suppose that the reply given by speaker B in (22) below:

has essentially the same structure as that shown in (21a), save that in place of the overt Fin head for we have a null Fin head, and that in place of the overt subject anyone we have a null PRO subject. In addition, if Foc is only a strong head in finite clauses, the Fin head remains in situ rather than raising to Foc.

The overall gist of Rizzi’s split CP hypothesis is that in structures containing a tropicalized and/or focalized constituent, CP splits into a number of different projections. In a clause containing both a tropicalized and a focalized constituent, CP splits into four separate projections – namely a Force Phrase, Topic Phrase, Focus Phrase and Finiteness Phrase. In a sentence containing a tropicalized but no focalized constituent, CP splits into three separate projections – namely into a Force Phrase, Topic Phrase and Finiteness Phrase. In a sentence containing a focalized but no tropicalized constituent, CP again splits into three projections – namely into a Force Phrase, Focus Phrase and Finiteness Phrase. However, in a structure containing no focalized or tropicalized constituents, Rizzi posits that Force and Finiteness features are syncretized (i.e. collapsed) onto a single head, with the result that CP does not split in this case: in other words, rather than being realized on two different heads, the relevant force and finiteness features are realized on a single head corresponding to the traditional C constituent (so that C is in effect a composite force/finiteness head). In simple terms, what this means is that C only splits into multiple projections in structures containing a tropicalized and/or focalized constituent.

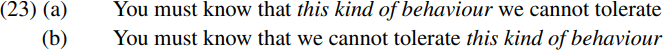

We can illustrate the conditions under which CP does (or does not) split in terms of the syntax of the that-clauses in (23) below:

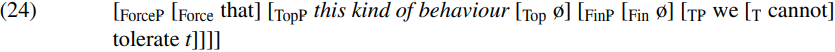

In (23a) the object this kind of behavior has been tropicalized, so forcing CP to split into three projections (ForceP, TopP and FinP) as shown in simplified form in (24) below:

By contrast, in (23b) there is no tropicalized or focalized constituent, hence CP does not split into multiple projections. Accordingly, only a single C constituent is projected which carries both finiteness and force features, as in (25) below (where DEC is a declarative force feature and FIN is a finiteness feature):

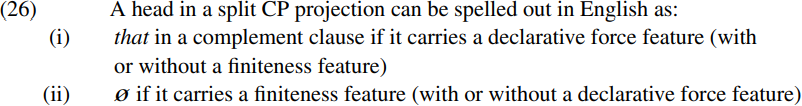

Rizzi posits that (in finite clauses) the relevant types of head are spelled out in the manner shown informally in (26) below:

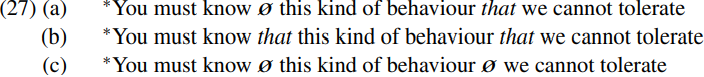

It follows from (26) that the Force head in (24) can be spelled out as that but not as ø, and that Fin can be spelled out as ø but not as that, so accounting for the ungrammaticality of:

(Irrelevantly, (27c) is grammatical if written with a colon between know and this kind of behavior and read as two separate sentences.) It also means that the syncretized (force/finiteness) C constituent in (25) can either be spelled out as that in accordance with (26i), or be given a null spellout in accordance with (26ii) as in (28) below:

In other words, Rizzi’s analysis provides a principled account of the (overt/null) spellout of finite declarative complementizers in English (though see Sobin 2002 for complications). (Complementizer spellout may be different in other languages – see e.g. Alexopoulou and Kolliakou 2002 on Greek.)

Before leaving the split CP analysis, an important technical complication should be pointed out (highlighted in relation to wh-movement). If we adopt Chomsky’s Phase Impenetrability Condition/PIC (under which the complement of a phase head is impenetrable to an external probe) and if we assume that not only CPs but also transitive VPs are phases, it follows that topicalization or focalization of the complement of a transitive verb will mean that the object must first move to the edge of the verb phrase before moving to the clause periphery. For the time being we set this issue aside here, returning to it because Chomsky’s work on phases assumes that verb phrases are analyzed as split projections in the manner outlined below.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة