Agreement and A-movement

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

307-8

الجزء والصفحة:

307-8

30-1-2023

30-1-2023

1709

1709

Agreement and A-movement

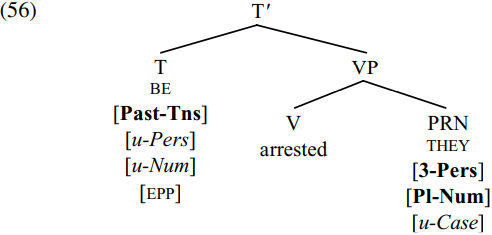

So far, we have seen that agreement plays an important role not only in valuing the  -features of T but also in valuing the case features of nominals. Chomsky (1998, 1999, 2001) goes further and suggests that agreement also plays an important role in A-movement operations. To see why, let’s return to consider the derivation of our earlier sentence (5B) They were arrested. Assume that the derivation proceeds as sketched earlier, with THEY being merged as the thematic complement of arrested, and the resulting VP in turn being merged with the tense auxiliary BE to form the structure (56) below:

-features of T but also in valuing the case features of nominals. Chomsky (1998, 1999, 2001) goes further and suggests that agreement also plays an important role in A-movement operations. To see why, let’s return to consider the derivation of our earlier sentence (5B) They were arrested. Assume that the derivation proceeds as sketched earlier, with THEY being merged as the thematic complement of arrested, and the resulting VP in turn being merged with the tense auxiliary BE to form the structure (56) below:

In (56), [T BE]is an active probe (by virtue of its uninterpretable person and number features) and has an uninterpretable [EPP] feature. It therefore searches for active nominal goals which can value and delete its person/number features, locating the pronoun THEY (which is active by virtue of its uninterpretable case feature and which has person and number features which match those of BE).

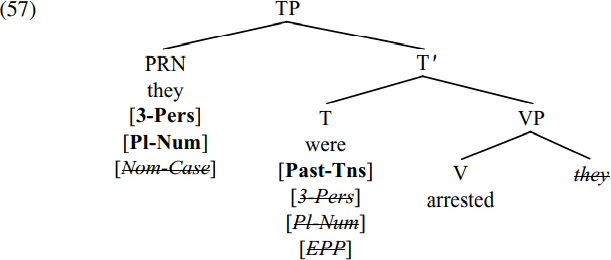

Since the matching goal THEY is a definite pronoun, the [EPP] feature of [T BE] cannot be deleted by merging an expletive in spec-TP, but rather can only be deleted by movement of the goal to spec-TP, in accordance with (45iii): accordingly, THEY moves to become the specifier of BE, thereby deleting the uninterpretable [EPP] feature of BE. Assuming that Feature-Copying, Nominative Case Assignment and Feature-Deletion work as before, the structure which is formed at the end of the TP cycle will be that shown below:

(To avoid excessive visual clutter, the trace copy of they left behind in VP-complement position is shown here simply as they, but is in fact an identical copy of they, containing the same features as they.) The TP in (57) will subsequently be merged with a null declarative-force C, so terminating the syntactic derivation. Since all uninterpretable features have been deleted, the derivation converges – i.e. results in a syntactic structure which can subsequently be mapped into well-formed phonetic and semantic representations.

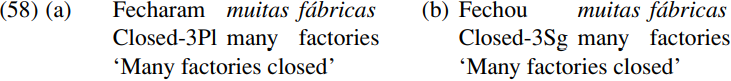

A key assumption underlying the analysis sketched here is that T triggers movement of a nominal goal with which it agrees in person and number. Interesting empirical support for this claim comes from European Portuguese. Costa (2001) notes that in colloquial Portuguese, an intransitive verb used in an unaccusative structure like that below can be either third person singular or third person plural if used with an in-situ postverbal argument as in (58) below:

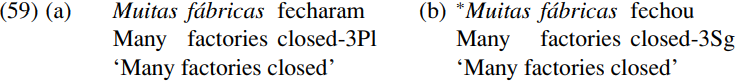

However, the postverbal argument (which originates as the complement of the verb) can only move in front of the verb into spec-TP if the verb (or, more accurately, the associated T-constituent) agrees with the subject in both person and number: cf.

This suggests that movement of the italicized nominal from VP-complement position to spec-TP is dependent on full person/number agreement between T and the nominal which it attracts. Costa follows Belletti (1988) in positing that in agreementless sentences like (58b), the postverbal argument is assigned partitive case by the verb (which, in a language in which nouns have a limited case morphology will surface in a form homophonous with the accusative); assignment of case to the complement makes it inactive, and so ineligible to undergo T-agreement – with the result that T surfaces in the agreementless default (third-person-singular) form. It may be that we find a related phenomenon in English sentence pairs such as:

In (60a) the italicized pronoun expression follows the verb be, is not assigned nominative case, does not trigger T-agreement and is not raised to spec-TP; by contrast in (60b) the italicized nominal is assigned nominative case, triggers T-agreement, and is moved to spec-TP. Accordingly, sentences like (60) provide empirical support for Chomsky’s claim that there is a close association between case, agreement and A-movement.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة