Feature valuation

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

284-8

الجزء والصفحة:

284-8

28-1-2023

28-1-2023

1860

1860

Feature valuation

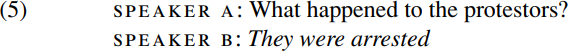

Let’s think through rather more carefully what it means to say that case is systematically related to agreement, and what the mechanism is by which case and agreement operate. To illustrate our discussion, consider the derivation of a simple passive such as that produced by speaker B below:

Here, discourse factors determine that a third-person-plural pronoun is required in order to refer back to the third-person-plural expression the protestors, and that a past-tense auxiliary is required because the event described took place in the past. So (as it were) the person/number features of they and the past-tense feature of were are determined in advance, before the items enter the derivation. By contrast the case feature assigned to they and the person/number features assigned to were are determined via an agreement operation in the course of the derivation: e.g. if the subject had been the singular pronoun one, the auxiliary would have been third person singular via agreement with one (as in One was arrested); and if THEY had been used as the object of a transitive verb (as in The police arrested them), it would have surfaced in the accusative form them rather than the nominative form they.

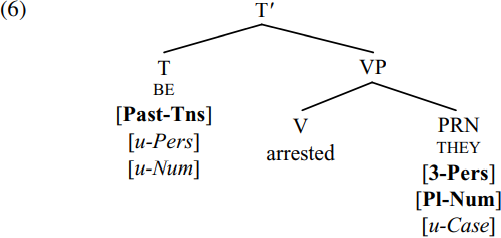

Generalizing at this point, let’s suppose that noun and pronoun expressions like THEY enter the syntax with their (person and number)  -features already valued, but their case feature as yet unvalued. (The notation THEY is used here to provide a case-independent characterization of the word which is variously spelled out as they/them/their depending on the case assigned to it in the syntax.) Using a transparent feature notation, let’s say that THEY enters the derivation carrying the features [3-Pers, Pl-Num, u-Case], where Pers = person, Pl = plural, Num = number, and u = unvalued. Similarly, let’s suppose that finite T constituents (like the tense auxiliary BE) enter the derivation with their tense feature already valued, but their person and number

-features already valued, but their case feature as yet unvalued. (The notation THEY is used here to provide a case-independent characterization of the word which is variously spelled out as they/them/their depending on the case assigned to it in the syntax.) Using a transparent feature notation, let’s say that THEY enters the derivation carrying the features [3-Pers, Pl-Num, u-Case], where Pers = person, Pl = plural, Num = number, and u = unvalued. Similarly, let’s suppose that finite T constituents (like the tense auxiliary BE) enter the derivation with their tense feature already valued, but their person and number  -features as yet unvalued (because they are going to be valued via agreement with a nominal goal). This means that BE enters the derivation carrying the features [Past-Tns, u-Pers, u-Num]. In the light of these assumptions, let’s see how the derivation of (5B) proceeds.

-features as yet unvalued (because they are going to be valued via agreement with a nominal goal). This means that BE enters the derivation carrying the features [Past-Tns, u-Pers, u-Num]. In the light of these assumptions, let’s see how the derivation of (5B) proceeds.

The pronoun THEY is the thematic complement of the passive verb arrested and so merges with it to form the VP arrested THEY. This is in turn merged with the tense auxiliary BE, forming the structure (6) below (where already-valued features are shown in bold, and unvalued features in italics):

Given Pesetsky’s Earliness Principle, T-agreement will apply at this point. Let’s suppose that agreement in such structures involves a c-command relation between a probe and a goal in which unvalued  -features on the probe are valued by the goal, and an unvalued case feature on the goal is valued by the probe. (In Chomsky’s use of these terms, it is the unvalued person/number features which serve as the probe rather than the item BE itself, but this is a distinction which we shall overlook throughout, in order to simplify exposition.) Since [T BE] is the highest head in the structure (6), it serves as a probe which searches for a c-commanded goal with an unvalued case feature, and locates the pronoun they. Accordingly, an agreement relation is established between the probe BE and the goal THEY. One reflex of this agreement relation is that the unvalued person and number features carried by the probe BE are valued by the goal THEY. Valuation here involves a Feature-Copying operation which we can sketch in general terms as follows (where

-features on the probe are valued by the goal, and an unvalued case feature on the goal is valued by the probe. (In Chomsky’s use of these terms, it is the unvalued person/number features which serve as the probe rather than the item BE itself, but this is a distinction which we shall overlook throughout, in order to simplify exposition.) Since [T BE] is the highest head in the structure (6), it serves as a probe which searches for a c-commanded goal with an unvalued case feature, and locates the pronoun they. Accordingly, an agreement relation is established between the probe BE and the goal THEY. One reflex of this agreement relation is that the unvalued person and number features carried by the probe BE are valued by the goal THEY. Valuation here involves a Feature-Copying operation which we can sketch in general terms as follows (where  and ß are two different constituents contained within the same structure, and where one is a probe and the other a goal):

and ß are two different constituents contained within the same structure, and where one is a probe and the other a goal):

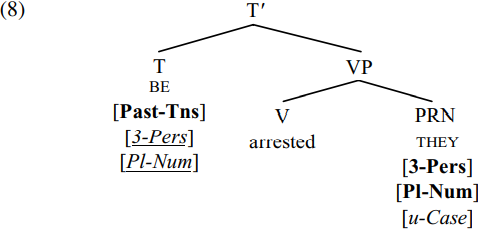

In consequence of the Feature-Copying operation (7), the values of the person/ number features of THEY are copied onto BE, so that the unvalued person and number features [u-Pers, u-Num] on be in (6) are assigned the [3-Pers, Pl-Num] values carried by THEY – as shown in (8) below, where the underlined features are those which have been valued via the Feature-Copying operation (7):

In consequence of the Feature-Copying operation (7), the values of the person/ number features of THEY are copied onto BE, so that the unvalued person and number features [u-Pers, u-Num] on be in (6) are assigned the [3-Pers, Pl-Num] values carried by THEY – as shown in (8) below, where the underlined features are those which have been valued via the Feature-Copying operation (7):

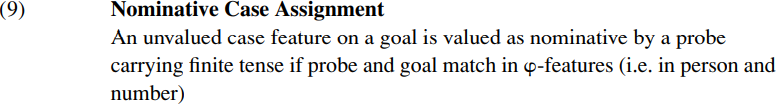

A second reflex of the agreement relation between BE and THEY is that the unvalued case feature [u-Case] carried by the goal THEY is valued by the probe BE. Since only auxiliaries with finite (present/past) tense have nominative subjects (and not e.g. infinitival auxiliaries), we can suppose that it is the finite tense features of the probe which are responsible for assigning nominative case to the goal. Accordingly, we can posit that nominative case assignment involves the kind of operation sketched informally below:

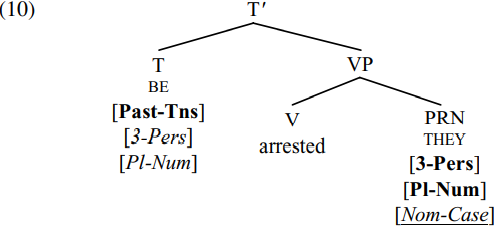

Since the person/number features of the probe BE match those of the goal THEY in (8), and since BE carries finite tense (by virtue of its [Past-Tns] feature), the unvalued case feature on THEY is valued as nominative, resulting in the structure shown in (10) below (where the underlined feature is the one valued as nominative in accordance with (9) above):

Since all the features carried by BE are now valued, BE can ultimately be spelled out in the phonology as the third-person-plural past-tense form were. Likewise, since all the features carried by THEY are also valued, they can ultimately be spelled out as the third-person-plural nominative form they. However, the derivation in (8) is not yet terminated: the [EPP] feature of T will subsequently trigger A-movement of they to become the structural subject of were, and the resulting TP they were arrested they will then be merged with a null declarative complementizer to form the structure ø they were arrested they: but since our immediate concern is with case and agreement, we skip over these details here.

Although we have given an essentially Chomskyan account of nominative case-marking in (9) and will continue to use it, a theoretically more elegant account would be to make use of Pesetsky and Torrego’s assumption that nominative case is a manifestation of a tense feature on T. On this alternative view, the [u-Case] feature on THEY in (8) would be replaced by a [u-Tense] feature which is valued as [Past-Tense] by the Feature-Copying operation in (7), with any (present- or past-) tensed form of the pronoun being spelled out as they. This solution is more elegant in two respects. Firstly, it eliminates the need for a Nominative Case Assignment operation, since nominative case assignment becomes a tense-copying operation which is simply a particular instance of the Feature-Copying operation in (7). Secondly, it avoids a potential violation of a UG principle which Chomsky terms the Inclusiveness Condition and which he says (1999, p. 2) ‘bars introduction of new elements (features) in the course of a derivation’. Under the analysis sketched in (8), THEY enters the derivation with an unvalued case feature which is then assigned the value nominative via agreement with a T constituent which has person, tense and number features. So it would seem that the value nominative is introduced into the derivation via a case-valuation operation like (9), leading to a potential violation of the Inclusiveness Condition. By contrast, under the alternative tense-copying analysis of nominative case, no new feature value is introduced into the derivation: instead, the existing [Past] value for the [Tns] feature on T is copied onto the subject.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة