Long-distance passivisation

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

264-7

الجزء والصفحة:

264-7

25-1-2023

25-1-2023

1755

1755

Long-distance passivisation

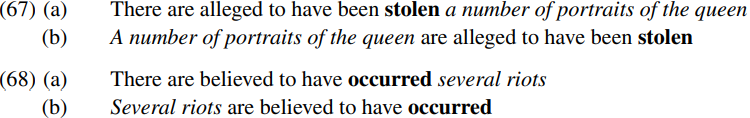

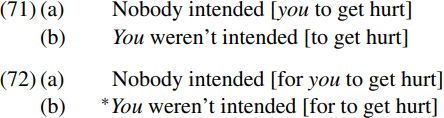

Thus far, the instances of passivisation which we have looked at have been clause-internal in the sense that they have involved movement from complement to subject position within the same clause/TP. However, passivisation can also apply across certain types of clause boundary – as can be illustrated in relation to structures such as (67) and (68) below:

It seems clear that the italicized expression in each case is the thematic complement of the bold-printed verb in the infinitive clause, so that a number of portraits of the queen is the thematic complement of the passive verb stolen in (67), and several riots is the thematic complement of the unaccusative verb occurred in (68). In (67a) and (68a), the italicized argument remains in situ as the complement of the bold-printed verb; but in (67b) and (68b) the italicized argument moves to become the structural subject of the auxiliary are. Let’s look rather more closely at the derivation of sentences like (68a) on the one hand and (68b) on the other.

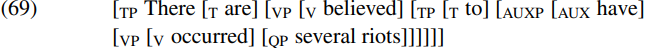

(68a) is derived as follows. The quantifier several merges with the noun riots to form the QP several riots. This QP merges with (and is θ-marked by) the unaccusative verb occurred to form the VP occurred several riots. The resulting VP merges with the perfect auxiliary have to form the AUXP have occurred several riots. This in turn merges with the infinitival tense particle to, so forming the TP to have occurred several riots. The resulting TP merges with the passive verb believed to form the VP believed to have occurred several riots. This then merges with the auxiliary are to form the T-bar are believed to have occurred several riots. A finite T like are has an [EPP] feature requiring it to have a specifier, and one way of satisfying this requirement is for expletive there to be merged in spec-TP, forming the TP shown in (69) below (simplified by not showing intermediate projections, and by not showing the internal structure of the QP several riots):

However, an alternative way of satisfying the [EPP] requirement for are to have a structural subject is for the closest nominal expression it c-commands (namely, several riots) to passivize (i.e. undergo A-movement) and thereby move into spec-TP, as shown by the dotted arrow in (70) below (where t is a trace copy of the moved QP several riots):

The kind of passivisation operation shown by the dotted arrow in (70) is sometimes termed long-distance passivisation, since it involves moving an argument out of a lower TP into the specifier position in a higher TP. Since operations which move a nominal into spec-TP are instances of A-movement, long-distance passivisation is yet another instance of the familiar A-movement operation. The TPs in (69,70) will subsequently be merged with a null complementiser marking the declarative force of the sentence, so deriving the overall structure associated with (68a,b).

The kind of passivisation operation shown by the dotted arrow in (70) is sometimes termed long-distance passivisation, since it involves moving an argument out of a lower TP into the specifier position in a higher TP. Since operations which move a nominal into spec-TP are instances of A-movement, long-distance passivisation is yet another instance of the familiar A-movement operation. The TPs in (69,70) will subsequently be merged with a null complementiser marking the declarative force of the sentence, so deriving the overall structure associated with (68a,b).

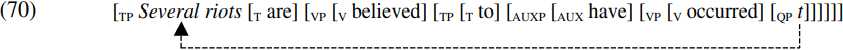

A key assumption made in (69, 70) is that the to-infinitive complement of the verb believed is a TP and not a CP. This is in line with our assumption that believe is an ECM verb when used with an infinitival complement, and that its complement is a defective clause (lacking the CP layer found in canonical clauses) and hence a TP. Recall that we have independent evidence from contrasts such as the following:

that an (italicized) expression contained within a TP complement like that bracketed in (71) can passivize, but an expression contained within a CP complement like that bracketed in (72) cannot. Consequently, the fact that several riots can passivize in (70) suggests that the to-infinitive complement of believed must be a TP, not a CP.

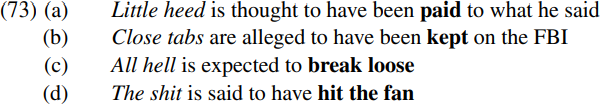

Evidence that we need to posit a long-distance passivisation operation comes from the fact that idiomatic nominals can undergo long-distance passivisation, as in the following examples:

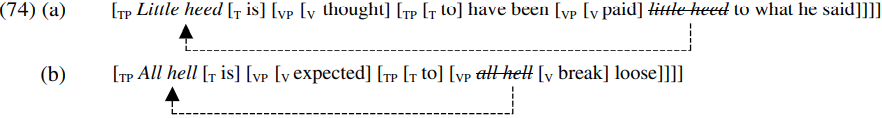

The italicized idiomatic nominals are normally used as the complement of the bold-printed verbs in (73a,b) and as the subject of the bold-printed expressions in (73c,d). So how do they come to be used as the subject of a higher passive clause in sentences like (73)? The answer is that they undergo long-distance passivisation. Note, incidentally, that sentences like (73c,d) suggest that long-distance passivisation can move subjects as well as objects. This is because (in conformity with the Attract Closest Principle), passivisation involves movement of the closest nominal which the relevant tense auxiliary c-commands. In a clause like (73a) in which the verb paid projects a complement but no subject, the auxiliary will trigger preposing of the complement little heed on the TP cycle because this is the closest nominal c-commanded by the auxiliary is – the relevant movement being shown in skeletal form in (74a) below; by contrast, in a clause like (73c) in which the verb break projects a subject all hell, the auxiliary is will trigger passivisation of all hell because this is the closest nominal c-commanded by is – as shown in (74b) below:

Although we have referred to the movement operation involved in structures like (74) as long-distance passivisation, it is in fact our familiar A-movement operation by which T attracts the closest nominal expression which it c-commands to move to spec-TP. (An incidental detail to note is that the TPs in (74) are subsequently merged with a null complementizer marking the declarative force of the sentence.)

Although we have referred to the movement operation involved in structures like (74) as long-distance passivisation, it is in fact our familiar A-movement operation by which T attracts the closest nominal expression which it c-commands to move to spec-TP. (An incidental detail to note is that the TPs in (74) are subsequently merged with a null complementizer marking the declarative force of the sentence.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة