Grammatical categories

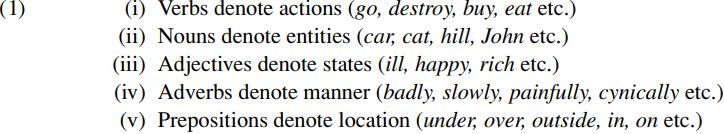

In §1.2, we noted that words are assigned to grammatical categories in traditional grammar on the basis of their shared semantic, morphological and syntactic properties. The kind of semantic criteria (sometimes called ‘notional’ criteria) used to categorise words in traditional grammar are illustrated in much-simplified form below:

However, semantically based criteria for identifying categories must be used with care: for example, assassination denotes an action but is a noun, not a verb; illness denotes a state but is a noun, not an adjective; in fast food, the word fast denotes the manner in which the food is prepared but is an adjective, not an adverb; and Cambridge denotes a location but is a noun, not a preposition.

The morphological criteria for categorizing words concern their inflectional and derivational properties. Inflectional properties relate to different forms of the same word (e.g. the plural form of a noun like cat is formed by adding the plural inflection -s to give the form cats); derivational properties relate to the processes by which a word can be used to form a different kind of word by the addition of an affix of some kind (e.g. by adding the suffix -ness to the adjective sad we can form the noun sadness). Although English has a highly impoverished system of inflectional morphology, there are nonetheless two major categories of word which have distinctive inflectional properties – namely nouns and verbs. We can identify the class of nouns in terms of the fact that they generally inflect for number, and thus have distinct singular and plural forms – cf. pairs such as dog/dogs, man/men, ox/oxen etc. Accordingly, we can differentiate a noun like fool from an adjective like foolish by virtue of the fact that only (regular, countable) nouns like fool – not adjectives like foolish – can carry the noun plural inflection -s:

There are several complications which should be pointed out, however. One is the existence of irregular nouns like sheep which are invariable and hence have a common singular/plural form (cf. one sheep, two sheep). A second is that some nouns are intrinsically singular (and so have no plural form) by virtue of their meaning: only those nouns (called count/countable nouns) which denote entities which can be counted have a plural form (e.g. chair – cf. one chair, two chairs); some nouns denote an uncountable mass and for this reason are called mass/uncountable/non-count nouns, and so cannot be pluralized (e.g. furniture – hence the ungrammaticality of ∗one furniture, ∗two furnitures). A third is that some nouns (like scissors and trousers) have a plural form but no countable singular form. A fourth complication is posed by noun expressions which contain more than one noun; only the head noun in such expressions can be pluralized, not any preceding noun used as a modifier of the head noun: thus, in expressions such as car doors, policy decisions, skate boards, horse boxes, trouser presses, coat hangers etc. the second noun is the head and can be pluralized, whereas the first noun is a modifier and so cannot be pluralized.

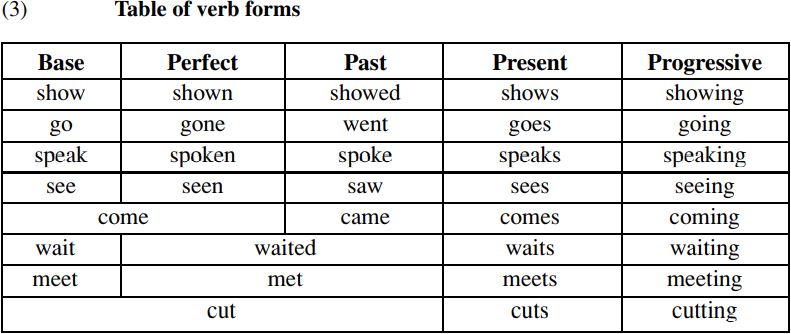

In much the same way, we can identify verbs by their inflectional morphology in English. In addition to their uninflected base form (= the citation form under which they are listed in dictionaries), verbs typically have up to four different inflected forms, formed by adding one of four inflections to the appropriate stem form: the relevant inflections are the perfect/passive participle suffix -n, the past-tense suffix -d, the third-person-singular present-tense suffix -s, and the progressive participle/gerund suffix -ing. Like most morphological criteria, however, this one is complicated by the irregular and impoverished nature of English inflectional morphology; for example, many verbs have irregular past or perfect forms, and in some cases either or both of these forms may not in fact be distinct from the (uninflected) base form, so that a single form may serve two or three functions (thereby neutralizing or syncretizing the relevant distinctions), as the table (3) below illustrates:

(The largest class of verbs in English are regular verbs which have the morphological characteristics of wait, and so have past, perfect and passive forms ending in the suffix -d.) The picture becomes even more complicated if we take into account the verb be, which has eight distinct forms (viz. the base form be, the perfect form been, the progressive form being, the past forms was/were, and the present forms am/are/is). The most regular verb suffix in English is -ing, which can be attached to the base form of almost any verb (though a handful of defective verbs like beware are exceptions).

The obvious implication of our discussion of nouns and verbs here is that it would not be possible to provide a systematic account of English inflectional morphology unless we were to posit that words belong to grammatical categories, and that a specific type of inflection attaches only to a specific category of word. The same is also true if we wish to provide an adequate account of derivational morphology in English (i.e. the processes by which words are derived from other words): this is because particular derivational affixes can only be attached to words belonging to particular categories. For example, the negative prefixes un-and in- can be attached to adjectives to form a corresponding negative adjective (as in pairs such as happy/unhappy and flexible/inflexible) but not to nouns (so that a noun like fear has no negative counterpart ∗unfear), nor to prepositions (so that a preposition like inside has no negative antonym ∗uninside). Similarly, the adverbialising (i.e. adverb-forming) suffix -ly in English can be attached only to adjectives (giving rise to adjective/adverb pairs such as sad/sadly) and cannot be attached to a noun like computer, or to a verb like accept, or to a preposition like with. Likewise, the nominalizing (i.e. noun-forming) suffix -ness can be attached only to adjective stems (so giving rise to adjective/noun pairs such as coarse/coarseness), not to nouns, verbs or prepositions. (Hence we don’t find -ness derivatives for a noun like boy, or a verb like resemble, or a preposition like down.) In much the same way, the comparative suffix -er can be attached to adjectives (e.g. tall/taller) and some adverbs (e.g. soon/sooner) but not to other types of word (e.g. woman/∗womanner); and the superlative suffix -est can attach to adjectives (e.g. tall/tallest) but not other types of word (e.g. down/∗downest; donkey/∗donkiest, enjoy/∗enjoyest). There is no point in multiplying examples here: it is clear that derivational affixes have categorial properties, and any account of derivational morphology will clearly have to recognize this fact (see e.g. Aronoff 1976 and Fabb 1988).

As we noted earlier, there is also syntactic evidence for assigning words to categories: this essentially relates to the fact that different categories of words have different distributions (i.e. occupy a different range of positions within phrases or sentences). For example, if we want to complete the four-word sentence in (4) below by inserting a single word at the end of the sentence in the — position:

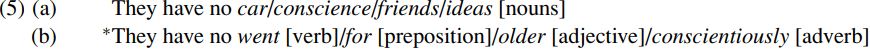

we can use an (appropriate kind of) noun, but not a verb, preposition, adjective, or adverb, as we see from:

So, using the relevant syntactic criterion, we can define the class of nouns as the set of words which can terminate a sentence in the position marked — in (4).

So, using the relevant syntactic criterion, we can define the class of nouns as the set of words which can terminate a sentence in the position marked — in (4).

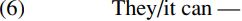

Using the same type of syntactic evidence, we could argue that only a verb (in its infinitive/base form) can occur in the position marked — in (6) below to form a complete (non-elliptical) sentence:

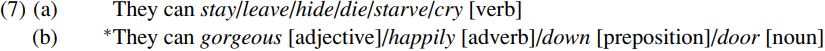

Support for this claim comes from the contrasts in (7) below:

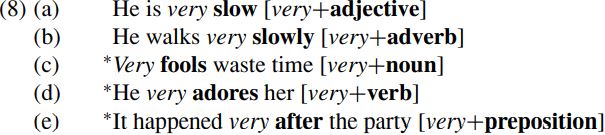

And the only category of word which can occur after very (in the sense of extremely) is an adjective or adverb, as we see from (8) below:

(But note that very can only be used to modify adjectives/adverbs which by virtue of their meaning are gradable and so can be qualified by words like very/rather/somewhat etc; adjectives/adverbs which denote an absolute state are ungradable by virtue of their meaning, and so cannot be qualified in the same way – hence the oddity of !Fifteen students were very present, and five were very absent, where ! marks semantic anomaly.)

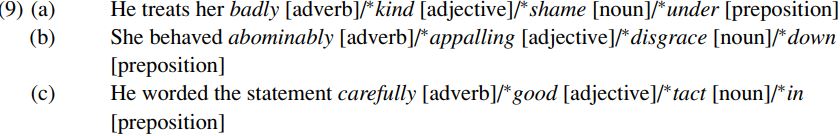

Moreover, we can differentiate adjectives from adverbs in syntactic terms. For example, only adverbs can be used to end sentences such as He treats her —, She behaved —, He worded the statement —:

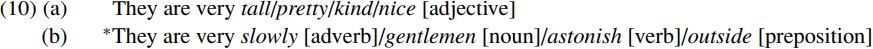

And since adjectives (but not adverbs) can serve as the complement of the verb be (i.e. can be used after be), we can delimit the class of (gradable) adjectives uniquely by saying that only adjectives can be used to complete a four-word sentence of the form They are very —:

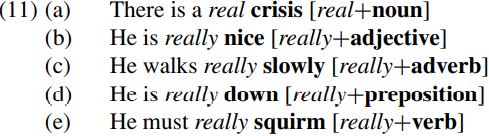

Another way of differentiating between an adjective like real and an adverb like really is that adjectives are used to modify nouns, whereas adverbs are used to modify other types of expression:

Another way of differentiating between an adjective like real and an adverb like really is that adjectives are used to modify nouns, whereas adverbs are used to modify other types of expression:

Adjectives used to modify a following noun (like real in There is a real crisis) are traditionally said to be attributive in function, whereas those which do not modify a following noun (like real in The crisis is real) are said to be predicative in function.

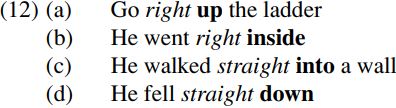

As for the syntactic properties of prepositions, they alone can be intensified by right in the sense of ‘completely’, or by straight in the sense of ‘directly’:

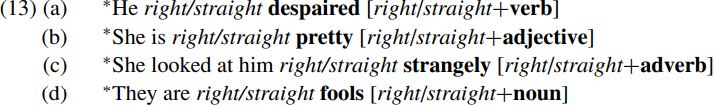

By contrast, other categories cannot be intensified by right/straight (in Standard English):

It should be noted, however, that since right/straight serve to intensify the meaning of a preposition, they can only be combined with those (uses of) prepositions which express the kind of meaning which can be intensified in the appropriate way (so that He made right/straight for the exit is OK, but ∗He bought a present right/straight for Mary is not).

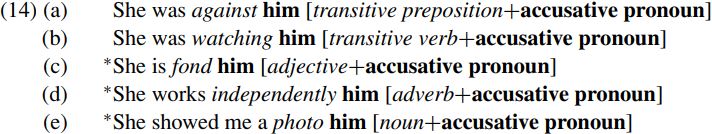

A further syntactic property of some prepositions (namely those which take a following noun or pronoun expression as their complement – traditionally called transitive prepositions) which they share in common with (transitive) verbs is the fact that they permit an immediately following accusative pronoun as their complement (i.e. a pronoun in its accusative form, like me/us/him/them):

Even though a preposition like with does not express the kind of meaning which allows it to be intensified by right or straight, we know it is a (transitive) preposition because it is invariable (so not e.g. a verb) and permits an accusative pronoun as its complement, e.g. in sentences such as He argued with me/us/him/them. (For obvious reasons, this test can’t be applied to prepositions used intransitively without any complement, like those in 12b,d above.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة