Principles of Universal Grammar

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

13-1

الجزء والصفحة:

13-1

28-7-2022

28-7-2022

2676

2676

Principles of Universal Grammar

If (as Chomsky claims) human beings are biologically endowed with an innate language faculty, an obvious question to ask is what is the nature of the language faculty. An important point to note in this regard is that children can in principle acquire any natural language as their native language (e.g. Afghan orphans brought up by English-speaking foster parents in an English-speaking community acquire English as their first language). It therefore follows that the language faculty must incorporate a theory of Universal Grammar/UG which enables the child to develop a grammar of any natural language on the basis of suitable linguistic experience of the language (i.e. sufficient speech input).

Experience of a particular language L (examples of words, phrases and sentences in L which the child hears produced by native speakers of L in particular contexts) serves as input to the child’s language faculty which incorporates a theory of Universal Grammar providing the child with a procedure for developing a grammar of L.

If the acquisition of grammatical competence is indeed controlled by a genetically endowed language faculty incorporating a theory of UG, then it follows that certain aspects of child (and adult) competence are known without experience, and hence must be part of the genetic information about language with which we are biologically endowed at birth. Such aspects of language would not have to be learned, precisely because they form part of the child’s genetic inheritance. If we make the (plausible) assumption that the language faculty does not vary significantly from one (normal) human being to another, those aspects of language which are innately determined will also be universal. Thus, in seeking to determine the nature of the language faculty, we are in effect looking for UG principles (i.e. principles of Universal Grammar) which determine the very nature of language.

But how can we uncover such principles? The answer is that since the relevant principles are posited to be universal, it follows that they will affect the application of every relevant type of grammatical operation in every language. Thus, detailed analysis of one grammatical construction in one language could reveal evidence of the operation of principles of Universal Grammar. By way of illustration, let’s look at question-formation in English. In this connection, consider the following dialogue:

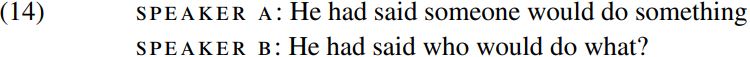

In (14), speaker B largely echoes what speaker A says, except for replacing someone by who and something by what. For obvious reasons, the type of question produced by speaker B in (14) is called an echo question. However, speaker B could alternatively have replied with a non-echo question like that in (15) below:

(15) Who had he said would do what?

If we compare the echo question He had said who would do what? in (14) with the corresponding non-echo question Who had he said would do what? in (15), we find that (15) involves two movement operations which are not found in (14). One is an auxiliary inversion operation by which the past-tense auxiliary had is moved in front of its subject he. The other is a wh-movement operation by which the wh-word who is moved to the front of the overall sentence, and positioned in front of had. (A wh-word is a word like who/what/where/when etc. beginning with wh.)

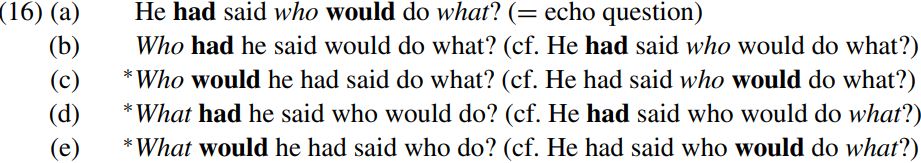

A closer look at questions like (15) provides evidence that there are UG principles which constrain the way in which movement operations may apply. An interesting property of the questions in (14) and (15) is that they contain two auxiliaries (had and would) and two wh-expressions (who and what). Now, if we compare (15) with the corresponding echo question in (14), we find that the first of the two auxiliaries (had) and the first of the wh-words (who) are moved to the front of the sentence in (15). If we try inverting the second auxiliary (would) and fronting the second wh-word (what), we end up with ungrammatical sentences, as we see from (16c–e) below (the preposed items are italicized, and the corresponding echo question is given in parentheses; (16a) is repeated from the echo question in (14B), and (16b) from (15)):

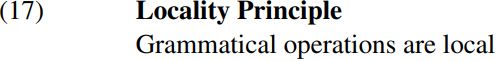

If we compare (16b) with its echo-question counterpart (16a) He had said who would do what? we see that (16b) involves preposing the first wh-word who and the first auxiliary had, and that this results in a grammatical sentence. By contrast, (16c) involves preposing the first wh-word who and the second auxiliary would; (16d) involves preposing the second wh-word what and the first auxiliary had; and (16e) involves preposing the second wh-word what and the second auxiliary would. The generalization which emerges from the data in (16) is that auxiliary inversion preposes the closest auxiliary had (i.e. the one nearest the beginning of the sentence) and likewise wh-fronting preposes the closest wh-expression who. The fact that two, quite distinct, different movement operations (auxiliary inversion and wh-movement) are subject to the same locality condition (which requires preposing of the most local – i.e. closest – expression of the relevant type) suggests that one of the principles of Universal Grammar incorporated into the language faculty is a Locality Principle which can be outlined informally as:

If we compare (16b) with its echo-question counterpart (16a) He had said who would do what? we see that (16b) involves preposing the first wh-word who and the first auxiliary had, and that this results in a grammatical sentence. By contrast, (16c) involves preposing the first wh-word who and the second auxiliary would; (16d) involves preposing the second wh-word what and the first auxiliary had; and (16e) involves preposing the second wh-word what and the second auxiliary would. The generalization which emerges from the data in (16) is that auxiliary inversion preposes the closest auxiliary had (i.e. the one nearest the beginning of the sentence) and likewise wh-fronting preposes the closest wh-expression who. The fact that two, quite distinct, different movement operations (auxiliary inversion and wh-movement) are subject to the same locality condition (which requires preposing of the most local – i.e. closest – expression of the relevant type) suggests that one of the principles of Universal Grammar incorporated into the language faculty is a Locality Principle which can be outlined informally as:

In consequence of (17), auxiliary inversion preposes the closest auxiliary, and wh-movement preposes the closest wh-expression. It seems reasonable to suppose that (17) is a principle of Universal Grammar (rather than an idiosyncratic property of question-formation in English). In fact, the strongest possible hypothesis we could put forward is that (17) holds of all grammatical operations in all natural languages, not just of movement operations; and indeed we shall see later that other types of grammatical operation (including agreement and case assignment) are subject to a similar locality condition. If so, and if we assume that abstract grammatical principles which are universal are part of our biological endowment, then the natural conclusion to reach is that (17) is a principle which is biologically wired into the language faculty, and which thus forms part of our genetic make-up.

A theory of grammar which posits that grammatical operations are constrained by innate principles of UG offers the important advantage that it minimizes the burden of grammatical learning imposed on the child (in the sense that children do not have to learn, for example, that auxiliary inversion affects the first auxiliary in a sentence, or that wh-movement likewise affects the first wh-expression). This is an important consideration, since we saw earlier that learnability is a criterion of adequacy for any theory of grammar – i.e. any adequate theory of grammar must be able to explain how children come to learn the grammar of their native language(s) in such a rapid and uniform fashion. The UG theory developed by Chomsky provides a straightforward account of the rapidity of the child’s grammatical development, since it posits that there are a universal set of innately endowed grammatical principles which determine how grammatical operations apply in natural language grammars. Since UG principles which are innately endowed are wired into the language faculty and so do not have to be learned by the child, this minimizes the learning load placed on the child, and thereby maximizes the learnability of natural language grammars.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة