Dynein

المؤلف:

I. R. Gibbons

المؤلف:

I. R. Gibbons

المصدر:

Cell Motility and Cytoskeleton

المصدر:

Cell Motility and Cytoskeleton

الجزء والصفحة:

الجزء والصفحة:

28-4-2016

28-4-2016

3139

3139

Dynein

Dyneins are microtubule-based motor proteins that use the energy released by the hydrolysis of ATP to move toward the minus end of a microtubule. The dyneins are classified as either cytoplasmic or flagellar (also known as axonemal), and the flagellar dyneins are further divided into outer and inner arm dyneins. The first dyneins to be identified were the flagellar dyneins, which are the arms that project from the A microtubules of ciliary and flagellar axonemes. Flagellar dyneins generate the sliding force between microtubules that is the basis for the propulsive bending of flagella (and cilia) that moves cells through fluids. Cytoplasmic dyneins move membranous organelles and kinetochores along microtubules and assist in assembling the mitotic spindle. Each dynein is a large molecular complex, composed of one or more large polypeptide chains of ~500kDa, known as heavy chains, and various accessory intermediate chains (50 to 140 kDa) and light chains (8 to 45 kDa). Often the heavy chain alone is referred to as a dynein. An ~350kDa portion of each heavy chain forms a large globular head domain, and the rest of the heavy chain extends from the head as a thin flexible stalk. The globular head contains the motor part of the molecule, the microtubule-binding site, and the ATP hydrolysis region. Two or three dynein heavy chains are often connected by their thin stalks to a common base. The base is made up of the intermediate and light chains, which are important for binding dynein to the organelles that it transports (its cargo).

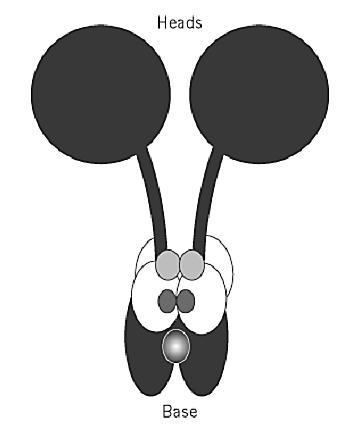

There are at least 12 different flagellar dynein heavy-chain genes. To date, only two uniquely cytoplasmic dynein heavy-chain genes have been identified. The major cytoplasmic dynein (Fig. 1( has a native molecular weight of 1.5×106 Da and contains two identical heavy chains associated with two 74-kDa intermediate chains, four 55-kDa light intermediate chains, and light chains of 22, 14, and 8 kDa. The heavy chain of this dynein is encoded by one gene, but multiple genes have been identified for the intermediate and light intermediate chains and for the 14-kDa light chain. The heavy chain of the minor cytoplasmic dynein is encoded by a unique gene, but the intermediate or light chains, with which it is presumed to be associated, have not yet been identified. Unlike cytoplasmic dynein, flagellar outer arm dyneins have two or three different heavy chains. Inner arm dyneins are either heterodimers or monomers of heavy chains and have various accessory polypeptides.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the overall structure of a cytoplasmic dynein.

Structural analysis of the heavy-chain motor domain indicates that the head is made up of seven lobes arranged in a ring surrounding a central cavity (1). Each heavy chain has four consensus nucleotide-binding sites known as P loops. The first P loop, P1, is believed to be the site of ATP binding and hydrolysis for force generation (2). The role of the other P loops is unknown. In the presence of vanadate, the heavy chains are cleaved by UV photolysis into two fragments at the first P loop. The different types of dynein hydrolyze MgATP at different rates. Dyneins can be attached to glass coverslips via their bases and their heads will bind microtubules. Using computer-enhanced video microscopy, it can be observed that this bound dynein translocates microtubules across the coverslip in the presence of ATP. The velocity of cytoplasmic dynein microtubule movement in vitro is ~1micron/second.

Flagellar dyneins attach via their base to one of the outer doublet microtubules (the A microtubule(

of the axoneme and bind directly to tubulin or to other axonemal microtubule-binding proteins. Their head domains bind to the B microtubule of the neighboring outer doublet in an ATP-sensitive manner and use the hydrolysis of ATP to push them toward the tip of the axoneme. Cytoplasmic dyneins bind to other cellular organelles. The mechanism by which dynein binds to these organelles is unknown. However, cytoplasmic dynein binds directly to artificial lipid membranes, liposomes, so dynein may bind directly to the organelle (3). There is also evidence, however, that an accessory protein complex, dynactin, is also important for cytoplasmic dynein binding to cargo (4). One dynactin subunit binds the dynein intermediate chain in vitro. Although they bind to different cargoes, cytoplasmic and flagellar outer arm dyneins have closely related cargo-binding subunits, the intermediate chains. The C-termini of the intermediate chains are conserved, and it is believed thatthey interact with the heavy chains. It is thought that the distinct intermediate-chain N-termini allow binding to different cargoes (5). Deletion of the cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain is lethal in multicellular organisms. Nonlethal mutations of cytoplasmic dynein heavy and light chains lead to axonal pathfinding defects and other pleiotropic developmental defects in Drosophila . Dyneins are regulated in vivo. During flagellar bending, only a subset of the flagellar dyneins function at a time. The phosphorylation state of an inner dynein-arm intermediate chain modulates this regulation (6.( Genetic methods have also identified several proteins that make up a dynein regulatory complex, although the mechanism of the complex remains unknown. Cytoplasmic dynein heavy-chain, intermediate-chain, and light-intermediate chains are phosphorylated in vivo, and phosphorylation of each has been implicated in regulating dynein.

References

1. M. Samso et al. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 276, 927–937.

2. I. R. Gibbons (1995) Cell Motility and Cytoskeleton 32, 136–144.

3. K. L. Ferro and C. A. Collins (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 4492–4496.

4. S. R. Gill et al. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 115, 1639–1650.

5. C. G. Wilkerson et al. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 129, 169–178.

6. G. Habermacher and W. S. Sale (1997) J. Cell Biol. 136, 167–176.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة