Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Prosody Stress and accent

المؤلف:

Ulrike B. Gut

المصدر:

A Handbook Of Varieties Of English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

824-45

2024-05-08

1491

Prosody

Stress and accent

The terms “stress” and “accent” are used in contradictory ways among researchers. Here, I will define “stress” as an abstract category that is stored as a feature of a syllable in the speaker’s mental lexicon and “accent” as its phonetic realization in speech. Word stress in NigE is in many cases different from that in British or American English (e.g. Simo Bobda 1997; Jowitt 1991). No systematic studies being available, a summary of various observations will be presented here.

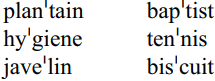

Simo Bobda (1997) describes a general tendency for stress shifted to the right. This can be seen in realizations of the words sa'lad, ma'ttress and pe'trol. Especially with words whose final syllable contains an [n] or an [i], stress is shifted to the right. Examples are:

Verbs tend to have stress on the last syllable if

– they have final obstruents (e.g. inter'pret, embar'rass, com'ment, soli'cit)

– or contain the affixes -ate, -ise, -ize, -fy or -ish

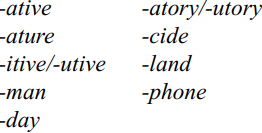

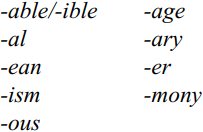

Other affixes that tend to attract stress include

Affixes that tend to bring stress to the preceding syllable are:

Equally, strong consonant clusters pull stress to the preceding syllable as in an'cestor. In compounds, the second element is stressed as for example in fire'wood and proof'read. In general, however, it must be noted that word stress patterns are not realized uniformly and that even among educated speakers (and even between productions of one and the same speaker) there is considerable variation in individual words.

Jowitt (1991) suggests that Nigerian speakers of English equate the primary stress in English with a high tone and the tertiary stress with a low tone. In order to avoid three consecutive low tones in e.g. interestingly, word stress is shifted to arrive at the pronunciation interes'tingly.

In continuous speech, the stressed syllables of words become potential places for sentence stress, i.e. accents realized by the speaker, with the number of accents determined by the speech tempo. In each utterance or sentence the most prominent accent is called the nucleus and tends to fall on the rightmost stressed syllable of an utterance, although pragmatic reasons such as emphasis may cause stress shifts. Sentence stress in NigE is rarely used for emphasis or contrast (Jibril 1986; Jowitt 1991; Gut 2003). Instead of producing “Mary did it” Nigerians tend to say “It was Mary who did it”.

Given information is rarely deaccented. For example, consider the sequence: A tiger and a mouse [..] saw a big lump of cheese lying on the ground. The mouse said: “[…] You don’t even like cheese”.

Nigerians produce an accent on the given information cheese in the last sentence whereas British speakers accentuate like.

An overall preference for “end-stress”, i.e. the placement of the nucleus, the most prominent accent, on the last word can been observed in NigE (Eka 1985; Gut 2003). In the dialogue (1) for example

British English speakers put a nucleus on I in (1b), whereas NigE speakers stress will most.

In general, in NigE many lexical items can receive stress that do not usually do so in British English. More stressed syllables are realized as accents in NigE speech than is the case in British English speech. In reading passage style, nearly all verbs, adjectives and nouns are accented in NigE (Udofot 2003; Gut 2003). In spontaneous speech, differences between British English and NigE are most pronounced with a large number of extra accented syllables in NigE (Udofot 2003).

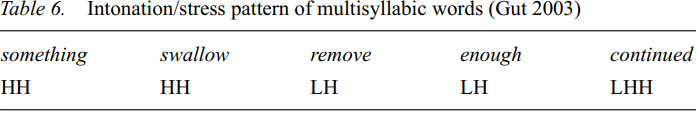

The phonetic realization of accents in NigE seems to be very different from that of other, especially native speaker varieties of English. In the languages of the world, the phonetic realization of accents can have different formats: In languages with “tonal accent” such as Swedish and Norwegian, different types of tones or pitch patterns are used on accented syllables. In languages with “dynamic accent” such as English or German, the phonetic parameters pitch, length and loudness are combined with different relative importance for the phonetic realization of accents. There seems to be an intricate relationship between accents and tone, not only because accents are very often produced with a phonetically high pitch. It has been suggested that in NigE accents are produced primarily by tone. Jowitt (1991) claims that stressed syllables receive a high tone whereas unstressed syllables receive a low tone. Gut (2003) found that tone in NigE is grammatically determined with lexical words receiving high tone on the stressed syllable and non-lexical words receiving low tone. The tonal patterns of some multisyllabic words are illustrated in Table 6 with L symbolizing a low tone and H symbolizing a high tone.

The stressed syllable of lexical words is produced with a high tone, which then spreads to the end of the word. Any unstressed syllables preceding the stressed syllable are produced with a low tone.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)