Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Changing the theory

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

71-3

25-3-2022

1428

Changing the theory

The theory of features is an empirical hypothesis, and is subject to revision in the face of appropriate data. It is not handed down by a higher authority, nor is it arbitrarily picked at the whim of the analyst. It is important to give critical thought to how the set of distinctive features can be tested empirically, and revised. One prediction of the theory which we have discussed, is that the two kinds of phonetic retroflex consonants found in Hindi and Telugu cannot contrast within a language. What would happen if a language were discovered which distinguished two degrees of retroflexion? Would we discard features altogether?

This situation has already arisen: the theory presented here evolved from earlier, similar theories. In an earlier theory proposed by Jakobson and Halle, retroflex consonants were described with the feature [flat]. This feature was also used to describe rounding, pharyngealization, and uvularization. While it may seem strange to describe so many different articulatory characteristics with a single feature, the decision was justified by the fact that these articulations share an acoustic consequence, a downward shift or weakening of higher frequencies. The assumption at that point was that no language could minimally contrast retroflexion, rounding, and pharyngealization. If a language has both [ʈ] and [kw], the surface differences in the realization of [flat], as retroflexion versus rounding, would be due to language-specific spell-out rules.

The theory would be falsified if you could show that rounding and pharyngealization are independent, and counterexamples were found. Arabic has the vowels [i a u] as well as pharyngealized vowels [i ʕ a ʕ uʕ ], which derive by assimilation from a pharyngealized consonant. If rounding and pharyngealization are both described by the feature [flat], it is impossible to phonologically distinguish [u] and [uʕ ]. But this is not at all inappropriate, since the goal is to represent phonological contrasts, not phonetic differences, because the difference between [u] and [uʕ ] is a low-level phonetic one. The relevance of Arabic – whether it falsifies the feature [flat] – depends on what you consider to be the purpose of features.

Badaga’s three-way vowel contrast challenges the standard theory as well. Little is known about this language: the contrast was originally reported by Emeneau (1961), and Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996) report that few speakers have a three-way contrast. The problem posed by this contrast has been acknowledged, but so far no studies have explored its nature.

Another prediction is that since uvular and round consonants are both [+flat], there should be no contrast between round and nonround uvulars, or between round velars and nonround uvulars, within a language. But a number of languages of the Pacific Northwest, including Lushootseed, have the contrast [k kw q qw]: this is a fact which is undeniably in the domain of phonology. The Dravidian language Badaga is reported to contrast plain and retroflex vowels, where any of the vowels [i e a o u] can be plain, half-retroflex, or fully retroflex. If [flat] indicates both retro-flexion and rounding, it would be impossible to contrast [u] and [u˞]. Such languages forced the abandonment of the feature [flat] in favor of the system now used.

The specific feature [flat] was wrong, not the theory of features itself. Particular features may be incorrect, which will cause us to revise or replace them, but revisions should be undertaken only when strong evidence is presented which forces a revision. Features form the foundation of phonology, and revision of those features may lead to considerable changes in the predictions of the theory. Such changes should be undertaken with caution, taking note of unexpected consequences. If the theory changes frequently, with new features constantly being added, this would rightly be taken as evidence that the underlying theory is wrong.

Suppose we find a language with a contrast between regular and sublingual retroflex consonants. We could accommodate this hypothetical language into the theory by adding a new feature [sublingual], defined as forming an obstruction with the underside of the tongue. This theory makes a new set of predictions: it predicts other contrasts distinguished by sublinguality. We can presumably restrict the feature to the [+coronal] segments on physical grounds. The features which distinguish coronal subclasses are [anterior] and [distributed], which alone can combine to describe four varieties of coronal – which actually exist in a number of Australian languages. With a new feature [sublingual], eight coronal classes can be distinguished: regular and sublingual alveolars, regular and sublingual dentals, regular and sublingual alveopalatals, and regular and sublingual retroflex consonants. Yet no such segments have been found. Such predictions need to be considered, when contemplating a change to the theory.

Similarly, recall the problem of “hyper-tense,” “plain tense,” “plain lax,” and “hyper-lax” high vowels across languages: we noted that no more than two such vowels exist in a language, governed by the feature [tense]. If a language were discovered with three or four such high vowels, we could add a feature “hyper.” But this makes the prediction that there could also be four-way contrasts among mid and low vowels. If these implications are not correct, the modification to the theory is not likely to be the correct solution to the problem. In general, addition of new features should be undertaken only when there is compelling evidence for doing so. The limited number of features actually in use is an indication of the caution with which features are added to the theory.

The case for labial. A classical case in point of a feature which was added in response to significant problems with the existing feature system is the feature [labial]. It is now accepted that feature theory should include this feature:

[labial]: sound produced with the lips

This feature was not part of the set of features proposed in Chomsky and Halle (1968). However, problems were noticed in the theory without [labial].

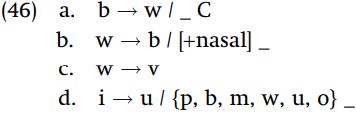

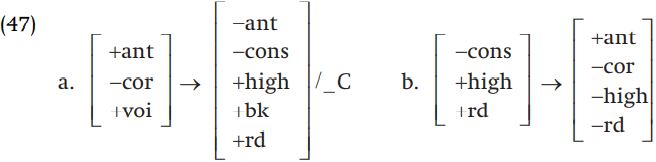

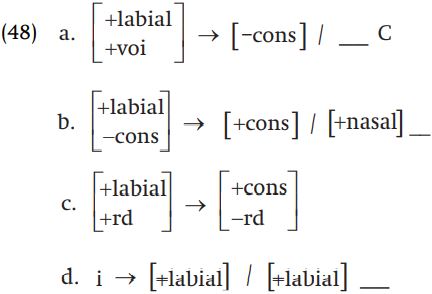

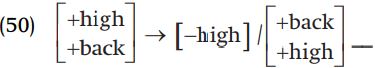

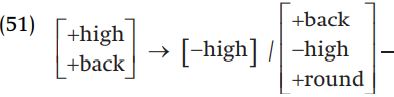

The argument for adding [labial] is that it makes rules better formalizable. It was noticed that the following types of rules, inter alia, are frequently attested (see Campbell 1974, Anderson 1974).

In the first three rules, the change from bilabial obstruent to rounded glide or rounded glide to labiodental obstruent is a seemingly arbitrary change, when written according to the then-prevailing system of features. There is so little in common between [b] and [w], given these features, that a change of [b] to [r] would be simpler to formulate as in (47b), and yet the change [b] ! [r] is unattested.

In the last rule of (46), no expression covers the class {p, b, m, w, u, o}: rather they correspond to the disjunction [+ant, -cor] or [+round].

These rules can be expressed quite simply with the feature [labial].

Feature redefinition. Even modifying definitions of existing features must be done with caution, and should be based on substantial evidence that existing definitions fail to allow classes or changes to be expressed adequately. One feature which might be redefined is [continuant]. The standard definition states that a segment is [+continuant] if it is produced with air continuously flowing through the oral cavity. An alternative definition is that a segment is [+continuant] if air flows continuously through the vocal tract. How do we decide which definition is correct? The difference is that under the first definition, nasals are [-continuant] and under the second definition, nasals are [+continuant].

If the first definition is correct, we expect to find a language where {p, t, tʃ , k, m, n, ŋ, b, d, dʒ , g} undergo or trigger a rule, and {f, s, θ, x, v, z, ð, γ} do not: under the “oral cavity” definition, [-continuant] refers to the class of segments {p, t, tʃ , k, m, n, ŋ, b, d, dʒ , g}. On the other hand, if the second hypothesis is correct, we should find a language where {n, m, n, f, s, x, v, x, γ} undergo or trigger a rule, and the remaining consonants {p, t, tʃ , k, b, d, dʒ , g} do not: under the “vocal tract” definition of [continuant], the feature specification [+continuant] would refer to the set {n, m, n, f, s, x, v, x, γ}.

Just as important as knowing what sets of segments can be referred to by one theory or another, you need to consider what groupings of segments cannot be expressed in a theory. Under either definition of [continuant], finding a process which refers to {p, t, k, b, d, g} proves nothing, since either theory can refer to this class, either as [-continuant] in the “oral cavity” theory or as [-continuant, -nasal] in the “vocal tract” theory. The additional feature needed in the “vocal tract” theory does complicate the rule, but that does not in itself disprove the theory. If you find a process referring to {n, m, n, f, s, x, v, x, γ}, excluding {p, t, k, b, d, g}, this would definitively argue for the “oral cavity” theory. Such a class can be referred to with the specification [+continuant] in the “oral cavity” theory, but there is no way to refer to that set under the “vocal tract” theory. As it stands, we have not found such clear cases: but at least we can identify the type of evidence needed to definitively choose between the theories. The implicit claim of feature theory is that it would be impossible for both kinds of rules to exist in human languages. There can only be one definition of any feature, if the theory is to be coherent.

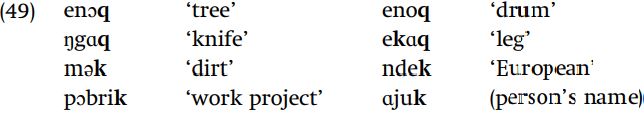

Central vowels. We will consider another case where the features face a problem with expressing a natural class, relating to the treatment of central versus back vowels. We saw that Kenyang [k] and [q] are in complementary distribution, with [q] appearing word-finally after the vowels [o], [ɔ], and [ɑ], and [k] appearing elsewhere. Representative examples are reproduced here.

Phonetic descriptions of vowels are not usually based on physiological data such as x-ray studies. Tongue positions are often deduced by matching sound quality with that of a standardly defined vowel: we assume that Kenyang schwa is central because it sounds like schwa, which is phonetically defined as being central.

Schwa does not cause lowering of k to q. In the standard account of vowels, [ə] differs from [ɔ] only in rounding, though phonetic tradition claims that these vowels also differ in being back ([ɔ]) versus central ([ə]). As previously discussed, this difference is attributed to a low-level, phonologically insignificant phonetic factor.

The problem which Kenyang poses is that it is impossible to formulate the rule of k-lowering if schwa is phonologically a mid back unrounded vowel. A simple attempt at formalizing the rule would be:

If schwa is [+back, -high, -round] it would satisfy the requirements of the rule so should cause lowering of /k/, but it does not: therefore this formulation cannot be correct. Since schwa differs from [ɔ] in being [-round], we might try to exclude [ə] by requiring the trigger vowel to be [+round].

But this formulation is not correct either, since it would prevent the nonround low vowel [ɑ] from triggering uvularization, which in fact it does do.

These data are a problem for the theory that there is only a two-way distinction between front and back vowels, not a three-way distinction between front, central, and back vowels. The uvularization rule of Kenyang can be formulated if we assume an additional feature, [ front], which characterizes front vowels. Under that theory, back vowels would be [+back, -front], front vowels would be [+front, -back], and central vowels would be [-back, -front]. Since we must account for this fact about Kenyang, the theory must be changed. But before adding anything to the theory, it is important to consider all of the consequences of the proposal.

front], which characterizes front vowels. Under that theory, back vowels would be [+back, -front], front vowels would be [+front, -back], and central vowels would be [-back, -front]. Since we must account for this fact about Kenyang, the theory must be changed. But before adding anything to the theory, it is important to consider all of the consequences of the proposal.

A positive consequence is that it allows us to account for Kenyang. Another possible example of the relevance of central vowels to phonology comes from Norwegian (and Swedish). There are three high, round vowels in Norwegian, whereas the standard feature theory countenances the existence of only two high rounded vowels, one front and one back. Examples in Norwegian spelling are do ‘outhouse,’ du ‘you sg,’ and dy ‘forbear!’. The vowel o is phonetically [u], and u and y are distinct nonback round vowels. In many transcriptions of Norwegian, these are transcribed as [dʉ] ‘you sg’ and [dy] ‘forbear!’, implying a contrast between front, central, and back round vowels. This is exactly what the standard view of central vowels has claimed should not happen, and it would appear that Norwegian falsifies the theory.

The matter is not so simple. The vowels spelled u versus y also differ in lip configuration. The vowel u is “in-rounded,” with an inward narrowing of the lips, whereas y is “out-rounded,” with an outward-flanging protrusion of the lips. This lip difference is hidden by the selection of the IPA symbols [ʉ] versus [y]. While it is clear that the standard theory does not handle the contrast, we cannot tell what the correct basis for maintaining the contrast is. We could treat the difference as a front ~ central ~ back distinction and disregard the difference in lip configuration (leaving that to phonetic implementation); or, we could treat the labial distinction as primary and leave the presumed tongue position to phonetic implementation.

Given that the theory of features has also accepted the feature [labial], it is possible that the distinction lies in [labial] versus [round], where the outrounded vowel is [+round, +labial] and in-rounded is [-round, +labial] – or vice versa. Unfortunately, nothing in the phonological behavior of these vowels gives any clue as to the natural class groupings of the vowels, so the problem of representing these differences in Norwegian remains unresolved. Thus the case for positing a distinct phonological category of central vowel does not receive very strong support from the vowel contrasts of Norwegian.

is [+round, +labial] and in-rounded is [-round, +labial] – or vice versa. Unfortunately, nothing in the phonological behavior of these vowels gives any clue as to the natural class groupings of the vowels, so the problem of representing these differences in Norwegian remains unresolved. Thus the case for positing a distinct phonological category of central vowel does not receive very strong support from the vowel contrasts of Norwegian.

A negative consequence of adding [front], which would allow the phonological definition of a class of central vowels, is that it defines unattested classes and segments outside the realm of vowels. The classical features could distinguish just [k] and [kj ], using [ back]. With the addition of [front], we would have a three-way distinction between k-like consonants which are [+front, -back], [-front, -back], and [-front, +back]. But no evidence at all has emerged for such a contrast in any language. Finally, the addition of the feature [front] defines a natural class [-back] containing front and central vowels, but not back vowels: such a class is not possible in the classical theory, and also seems to be unattested in phonological rules. This may indicate that the feature [front] is the wrong feature – at any rate it indicates that further research is necessary, in order to understand all of the ramifications of various possible changes to the theory.

back]. With the addition of [front], we would have a three-way distinction between k-like consonants which are [+front, -back], [-front, -back], and [-front, +back]. But no evidence at all has emerged for such a contrast in any language. Finally, the addition of the feature [front] defines a natural class [-back] containing front and central vowels, but not back vowels: such a class is not possible in the classical theory, and also seems to be unattested in phonological rules. This may indicate that the feature [front] is the wrong feature – at any rate it indicates that further research is necessary, in order to understand all of the ramifications of various possible changes to the theory.

Thus the evidence for a change to feature theory, made to handle the problematic status of [ə] in Kenyang phonology, would not be sufficiently strong to warrant complete acceptance of the new feature. We will suspend further discussion of this proposal until later, when nonlinear theories of representation are introduced and answers to some of the problems such as the unattested three-way contrast in velars can be considered. The central point is that changes in the theory are not made at will: they are made only after considerable argumentation and evidence that the existing theory is fundamentally inadequate.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)