Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The foot

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

124-10

22-3-2022

2973

The foot

So far we have been assuming that syllables group into words, with some words being composed of only a single syllable. Strictly, however, the word is not a phonological unit, but a morphological and syntactic one; and as we shall see in the next section, phonological processes are no great respecters of word boundaries, operating between words just as well as within them. The next biggest phonological unit above the syllable is the foot.

The normally accepted definition is that each phonological foot starts with a stressed syllable (though we shall encounter an apparent exception below), and continues up to, but not including, the next stressed syllable. This means that cat in a hat consists of two feet, the first containing cat in a, and the second, hat. Although cat flap consists of only two words (or indeed one, if we agree this is a compound), as opposed to four in cat in a hat, it also consists of two feet, this time one for each syllable, since both cat and flap bear some degree of stress. Indeed, because English is a stress-timed language, allowing approximately the same amount of time to produce each foot (as opposed to syllable-timed languages, like French, which devote about the same amount of time to each syllable regardless of stress), cat in a hat and cat flap will have much the same phonetic duration. The same goes for the cat sat on the mat, with rather few unstressed syllables between the stressed ones, and as snug as a bug in a rug, with a regular pattern of two unstressed syllables to each stress. This isochrony of feet, whereby feet last for much the same time regardless of the number of syllables in them, is responsible for the characteristic rhythm of English.

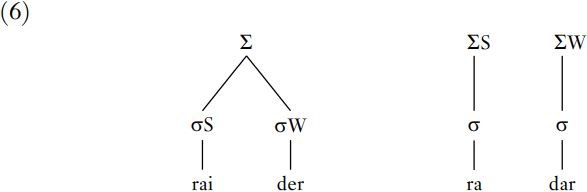

Like syllables, feet can also be contrasted as stronger and weaker. Sometimes, there will be more than one foot to the word; for instance, as we saw earlier, a word like ‘raider, with primary stress on the first syllable and no stress on the second, can be opposed to ‘ra,dar, with primary versus secondary stress. It is not possible to capture this distinction using only syllable-based trees, since both raider and radar have a stronger first syllable and a weaker second syllable. However, these two W nodes are to be interpreted in two different ways, namely as indicating no stress in raider, but secondary stress in radar. To clarify the difference, we must recognize the foot. Raider then has a single foot, while radar has two, the first S and the second W. Recall that small sigma (σ) indicates a syllable, and capital sigma (Σ), a foot.

In other cases, the same number of feet may be spread over more than one word, so that ‘cat flap has two feet, related as S versus W, while ,cat in a ‘hat also has two feet, although here the first foot is larger, including in a as well as cat, and the prominence relationship of W S reflects the fact that cat flap is a compound bearing initial primary stress, while cat in a hat is a phrase, with main stress towards the end.

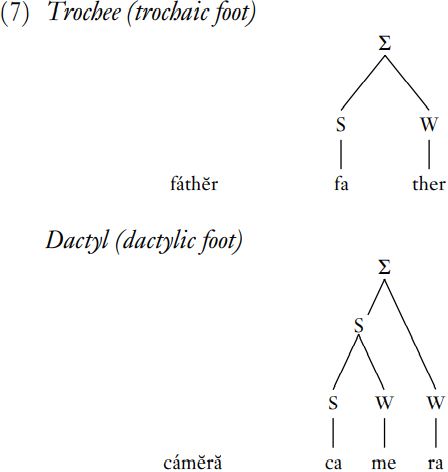

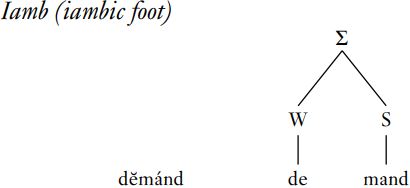

Feet can also be classified into types, three of which are shown in (7). The iambic type, structured W S, contradicts the claim above that all feet begin with a stressed syllable; but in fact, at the connected speech level, the first, unstressed syllable in such cases will typically become realigned, attaching to the preceding foot. So, in cup of tea, the weak syllable of will be more closely associated with the preceding stronger syllable, with which it then forms a trochaic foot, than with the following one, as evidenced by the common contraction cuppa for cup of.

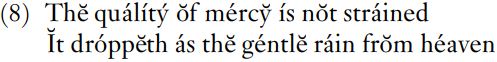

These foot types are important in scansion, or analyzing verse. For example, the blank verse of Shakespeare’s plays involves iambic pentameters: each line has five iambic feet, as shown in the metre of two lines from The Merchant of Venice (8).

To take a less exalted example, (9) shows two lines with rather different metrical structure. The first consists of two dactyls and a final ‘degenerate’ foot composed of a single stressed syllable. Note that a foot of this kind, like dock here, or any monosyllabic word like bit, cat in normal conversation, cannot really be labelled as S or W: since stress is relational, it requires comparison with surrounding feet. The second line is again made up of iambic feet.

Finally (taking another nursery rhyme, since these often have particularly clear and simple metre), a line like Máry˘, Máry˘ quíte co˘ntráry˘ is composed of four trochaic feet.

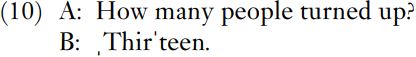

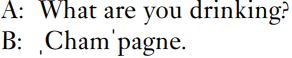

Poetry also provides an excellent illustration of the English preference for alternating stress. It does not especially matter whether we have sequences of SWSWSWSW, or SWWSWWSWWSWW; but what does matter is avoiding either lapses, where too many unstressed syllables intervene between stresses, or clashes, where stresses are adjacent, with no unstressed syllables in between at all. The English process of Iambic Reversal seems designed precisely to avoid stress clashes of this kind. It affects combinations of words which would, in isolation, have final stress on the first word, and initial stress on the second. For instance, (10) shows that the citation forms (that is, the formal speech pronunciation of a word alone, rather than in a phrase) of thirteen and champagne have final stress.

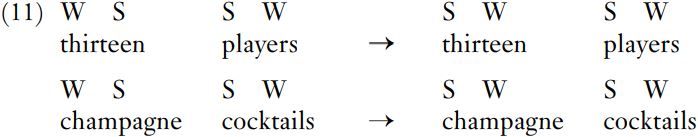

However, when final-stressed words like thirteen and champagne form phrases with initial-stressed ones like players or cocktails, the stress on the first word in each phrase moves to the left, so that in ‘thir,teen ‘players and ‘cham,pagne ‘cocktails, both words have initial stress. This is clearly related to the preference of English speakers for eurhythmic alternation of stronger and weaker syllables, as illustrated in (11).

If these words retained their normal stress pattern once embedded in the phrases, we would find clashing sequences of WSSW, as shown on the left of (11), in violation of eurhythmy; consequently, the prominence pattern of the first word is reversed, changing from an iamb to a trochee – hence the name Iambic Reversal. The result is a sequence of two trochaic feet, giving SWSW and ideal stress alternation.

It is also possible, however, for the normal stress patterns of words to be disrupted and rearranged in an altogether less regular and predictable way, reflecting the fact that stress is not only a phonological feature, but can also be used by speakers to emphasize a particular word or syllable. If one speaker mishears or fails to hear another, an answer may involve stressing both syllables in a word, in violation of eurhythmy: so, the question What did you say? may quite appropriate elicit the response ‘thir’ teen. Similarly, although phrases typically have final stress, a speaker emphasizing the first word may well produce the pattern a ‘cat in a ‘hat, rather than a ,cat in a ‘hat. This is partly what makes the study of intonation, the prominence patterns of whole utterances, so complicated. It is true that there is a typical ‘tune’ associated with each utterance type in English: for instance, questions typically have raised pitch towards the end of the sentence, while statements have a pitch shift downwards instead. However, the stress patterns of particular words (which may themselves be altered for emphasis) interact with these overall tunes in a highly complex and fluid way.

Furthermore, speakers can use stress and intonation to signal their attitude to what they are saying; so that although No spoken with slightly dropping pitch signals neutral agreement, it may also be produced with rising pitch to signal surprise, or indeed with rising, falling, and rising intonation, to show that the speaker is unsure or doubtful. In addition,

intonation is just as subject to change over time, and under sociolinguistic pressures, as any other area of phonology. To take one case in point, there is currently a growing trend for younger women in the south-east of England in particular to extend to statements the high rising tune characteristic of questions, so that She’s going out and She’s going out? will have the same characteristic intonation pattern for these speakers. Whatever the source of this innovation (with the influence of Australian television soaps like Neighbors being a favorite popular candidate), it shows that intonation is not static, and that there is no single, necessary connection between particular patterns and particular utterance types. These complexities, combined with the fact that the analysis of intonation has its own (highly complex and often variable) technical terms and conventions, mean that it cannot be pursued further here.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)