Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Causal mechanisms for language change

المؤلف:

Vyvyan Evans and Melanie Green

المصدر:

Cognitive Linguistics an Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

C4P127

2025-12-13

292

Causal mechanisms for language change

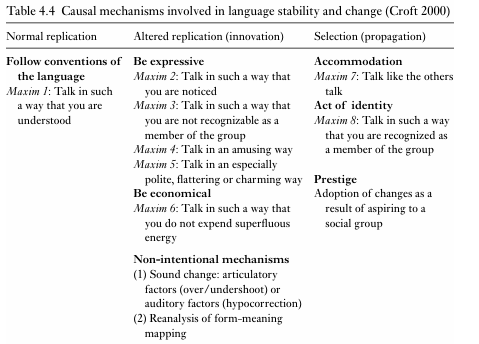

In this section, we consider the social mechanisms that give rise to replication, resulting in normal replication, altered replication (innovation), and selection (propagation). Because the Theory of Utterance Selection is usage-based, we are concerned with utterances (usage events), which are embedded in linguistic interaction. For this reason, we require a theory that explains the nature of, and the motivations for, the kinds of interactions that language users engage in.

Recall that the usage-based view of language change assumes that these inter actions preserve language stability (by following linguistic conventions), bring about innovation (by breaking linguistic conventions) and give rise to propagation due to the differential selection of certain kinds of linguemes by language users in a sociocultural context, resulting in the establishment of new conventions. In order to account for human behaviour in linguistic interaction, Croft adopts a model proposed by Rudi Keller (1994), which describes linguistic interaction in terms of a number of maxims. The hypermaxims and maxims discussed below are therefore drawn from Keller’s work. Note, however, that while we have numbered the maxims for our purposes, these numbers do not derive from Keller’s work.

Keller views linguistic behaviour as a form of social action, in keeping with functional approaches to language. He proposes a number of maxims in order to model what language users are doing when they use language. The maxims described here are in service of a more general principle, which Keller (1994) calls a hypermaxim. In Keller’s terms, this is the hypermaxim of linguistic interaction and can be stated as follows:

Croft argues that by observing the various maxims in the service of fulfilling the hypermaxim of linguistic interaction, speakers facilitate normal replication, altered replication and selection, and thus bring about language change.

Normal replication

As we have seen, a theory of language change must be able to account for the relative stability of language as well as offering an explanation for how and why language changes. Recall that convention is crucial to the success of language as a communicative system. Croft argues that normal replication, which enables stability, arises from speakers following the maxim stated in (8):

Of course, this maxim states the rather obvious but no less important fact that speakers normally intend to be understood in linguistic interaction. In order to be understood, speakers follow the conventions of the language. Hence, the unintended consequence of observing Maxim 1 is normal replication: stability in language.

Altered replication

Croft argues that innovation arises because, in addition to wanting to be under stood, speakers also have a number of other goals. These are summarised by the series of maxims stated in (9)–(12).

These maxims relate to the ‘expressive’ function of language. In other words, in order to observe the hypermaxim (achieve one’s goals in linguistic interaction), speakers might follow Maxims (2)–(5). However, in following these maxims, the speaker may need to break the conventions of the language. As a consequence, innovation or altered replication takes place. We will look at some specific examples below. A further maxim posited by Keller, which may be crucial in altered replication, is stated in (13):

This maxim relates to the notion of economy. The fact that frequently used terms in a particular linguistic community are often shortened may be explained by this maxim. Croft provides an example from the community of Californian wine connoisseurs. While in the general English-speaking community wine varieties are known by terms like Cabernet Sauvignon, Zinfandel and Chardonnay, in this speech community, where wine is a frequent topic of conversation, these terms have been shortened to Cab, Zin and Chard. As Croft (2000: 75) observes, ‘The energy expended in an utterance becomes superfluous, the more frequently it is used, hence the shorter the expression for it is likely to be(come).’ While some theories of language treat economy in terms of mental representation (as a function of psycholinguistic processing costs), Croft argues that Maxim 6, which essentially relates to economy, actually relates to a speaker’s interactional goals in a communicative context. In other words, Maxim 6 can only be felicitously followed when it doesn’t contravene other maxims, like Maxim 1. It is only in a context involving wine connoisseurs, for instance, that the diminutive forms do not flout Maxim 1 and are therefore felicitous.

The observation of the maxims we have considered so far is intentional: deliberate on the part of the language user. However, there are a number of mechanisms resulting in altered replication that are non-intentional. These processes are nevertheless grounded in usage events. We briefly consider these here.

Altered replication: sound change

The first set of non-intentional mechanisms relates to regular sound change. Sound change occurs when an allophone, the speech sound that realises a phoneme, is replicated in altered form. Because the human articulatory system relies on a highly complex motor system in producing sounds, altered replication can occur through ‘errors’ in articulation. In other words, the articulatory system can overshoot or undershoot the sound it is attempting to produce, giving rise to a near (slightly altered) replication. Of course, it seems unlikely that an individual’s speech error can give rise to a change that spreads through out an entire linguistic community, but the famous sociolinguist William Labov (1994) suggests that mechanisms like overshoot or undershoot can give rise to vowel chain shifts in languages.

A chain shift involves a series of sound changes that are related to one another. This typically involves the shift of one sound in phonological space which gives rise to an elaborate chain reaction of changes. Chain shifts are often likened to a game of musical chairs, in which one sound moves to occupy the place of an adjacent pre-shift sound, which then has to move to occupy the place of another adjacent sound in order to remain distinct, and so on. The net effect is that a series of sounds move, forming a chain of shifts and affecting many of the words in the language.

A well known example of a chain shift is the Great English Vowel Shift, which took effect in the early decades of the fifteenth century and which, by the time of Shakespeare (1564–1616), had transformed the sound pattern of English. The Great Vowel Shift affected the seven long vowels of Middle English, the English spoken from roughly the time of the Norman conquest of England (1066) until about half a century after the death of Geoffrey Chaucer (around 1400). What is significant for our purposes is that each of the seven long vowels was raised, which means that they were articulated with the tongue higher in the mouth. This corresponds to a well known tendency in vowel shifts for long vowels to rise, while short vowels fall.

Labov (1994) suggests that chain shifts might be accounted for in purely articulatory terms. In other words, the tendency for long vowels to undergo raising in chain shifts might be due to articulatory pressure for maintaining length, which results in the sound being produced in a higher region of the mouth. This is the phenomenon of overshoot. Undershoot applies to short vowels, but in the opposite direction (lowering). Crucially, this type of mechanism is non-intentional because it does not arise from speaker goals but from purely mechanical system-internal factors.

Another non-intentional process that results in sound change is assimilation. Croft, following suggestions made by Ohala (1989), argues that this type of sound change might be accounted for not by articulatory (sound-producing) mechanisms, but by non-intentional auditory (perceptual) mechanisms. Assimilation is the process whereby a sound segment takes on some of the char acteristics of a neighbouring sound. For instance, many French vowels before a word-final nasal have undergone a process called nasalisation. Nasal sounds – like [m] in mother, [n] in naughty and the sound [ŋ] at the end of thing are produced by the passage of air through the nasal cavity rather than the oral cavity. In the process of nasalisation, the neighbouring vowel takes on this sound quality, and is articulated with nasal as well as oral airflow. For instance, French words like fin ‘end’ and bon ‘good’ feature nasalised vowels. The con sequence of this process is that in most contexts the final nasal segment [n] is no longer pronounced in Modern French words, because the presence of a nasalised vowel makes the final nasal sound redundant. Notice that the spelling retains the ‘n’, reflecting pronunciation at an earlier stage in the language before this process of sound change occurred.

The process that motivates assimilation of this kind is called hypocorrection. In our example of hypocorrection, the vowel sound is reanalysed by the language user as incorporating an aspect of the adjacent sound, here the nasal. However, this process of reanalysis is non-intentional: it is a covert process that does not become evident to speakers until the nasalisation of the vowel results in the loss of the nasal sound that conditioned the reanalysis in the first place.

Altered replication: form-meaning reanalysis

Altered replication is not restricted to sound change, but can also affect symbolic units. Recall that symbolic units are form-meaning pairings. Language change that affects these units can be called form-meaning reanalysis (Croft uses the term form-function reanalysis). Form-meaning reanalysis involves a change in the mapping between form and meaning. Consider examples (14) and (15).

What concerns us here is the meaning of the be going to construction. In example (14), this expression describes a physical path of motion, while in (15) it describes future time, which is the more recent meaning associated with this construction. This is an example of a type of form-meaning reanalysis known as grammaticalisation, an issue to which we return in detail in Part III of the book (Chapter 21). As we noted above, the term reanalysis does not imply a deliberate or intentional process. Instead, the reanalysis is non-intentional, and derives from pragmatic (contextual) factors.

Selection

We now turn to the social mechanisms responsible for selection, and look at how the innovation is propagated through a linguistic community so that it becomes conventionalised. In the Theory of Utterance Selection, mechanisms of selection operate over previously used variants. One such mechanism proposed by Keller is stated in (16).

Croft argues that this maxim is closely related to the theory of accommodation (Trudgill 1986). This theory holds that interlocutors often tend to accommodate or ‘move towards’ the linguistic conventions of those with whom they are interacting in order to achieve greater rapport or solidarity. A variant of Maxim 7 posited by Keller is stated in (17)

This maxim elaborates Maxim 7 in referring explicitly to group identity. From this perspective, the way we speak is an act of identity, as argued by LePage and Tabouret-Keller (1985). In other words, one function of the language we use is to identify ourselves with a particular social group. This means that sometimes utterances are selected that diverge from a particular set of conventions as a result of the desire to identify with others whose language use is divergent from those conventions.

Table 4.4 summarises the various mechanisms for language change and language stability that have been described in this section. Of course, this discussion does not represent an exhaustive list of the mechanisms that are involved in language change, but provides representative examples.

In sum, we have seen that the Theory of Utterance Selection is a usage based theory of language change because it views language as a system of use governed by convention. Language change results from breaking with convention and selecting some of the new variants created as a result of this departure. While the propagation of new forms can be due to intentional mechanisms relating to the expressive functions associated with language, it also involves non-intentional articulatory and perceptual mechanisms. Finally, the selection of variants is due to sociolinguistic processes such as accommodation, identity and prestige.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)