The Ehrenfest classification of phase transitions

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins، Julio de Paula

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins، Julio de Paula

المصدر:

ATKINS PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY

المصدر:

ATKINS PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY

الجزء والصفحة:

ص129-131

الجزء والصفحة:

ص129-131

2025-11-12

2025-11-12

238

238

The Ehrenfest classification of phase transitions

There are many different types of phase transition, including the familiar examples of fusion and vaporization and the less familiar examples of solid–solid, conducting superconducting, and fluid–superfluid transitions. We shall now see that it is possible to use thermodynamic properties of substances, and in particular the behaviour of the chemical potential, to classify phase transitions into different types. The classification scheme was originally proposed by Paul Ehrenfest, and is known as the Ehrenfest classification.

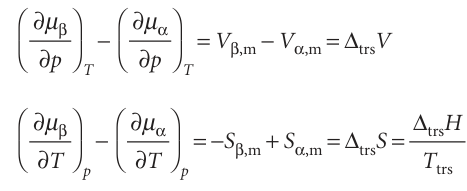

Many familiar phase transitions, like fusion and vaporization, are accompanied by changes of enthalpy and volume. These changes have implications for the slopes of the chemical potentials of the phases at either side of the phase transition. Thus, at the transition from a phase α to another phase β,

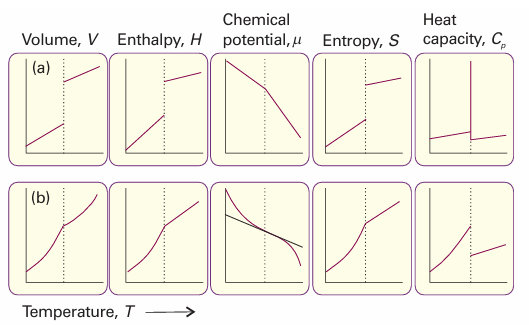

Because ∆trsV and ∆trsH are non-zero for melting and vaporization, it follows that for such transitions the slopes of the chemical potential plotted against either pressure or temperature are different on either side of the transition (Fig. 4.16a). In other words, the first derivatives of the chemical potentials with respect to pressure and tempera ture are discontinuous at the transition. A transition for which the first derivative of the chemical potential with respect to temperature is discontinuous is classified as a first-order phase transition. The constant-pressure heat capacity, Cp, of a substance is the slope of a plot of the enthalpy with respect to temperature. At a first-order phase transition, H changes by a finite amount for an infinitesimal change of temperature. Therefore, at the transition the heat capacity is infinite. The physical reason is that heating drives the transition rather than raising the temperature. For example, boiling water stays at the same tempera ture even though heat is being supplied.

Fig. 4.16 The changes in thermodynamic properties accompanying (a) first-order and (b) second-order phase transitions.

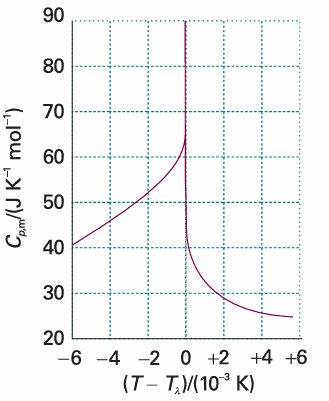

A second-order phase transition in the Ehrenfest sense is one in which the first derivative of µ with respect to temperature is continuous but its second derivative is discontinuous. A continuous slope of µ (a graph with the same slope on either side of the transition) implies that the volume and entropy (and hence the enthalpy) do not change at the transition (Fig. 4.16b). The heat capacity is discontinuous at the transition but does not become infinite there. An example of a second-order transition is the conducting–superconducting transition in metals at low temperatures.2 The term λ-transition is applied to a phase transition that is not first-order yet the heat capacity becomes infinite at the transition temperature. Typically, the heat capacity of a system that shows such a transition begins to increase well before the transition (Fig. 4.17), and the shape of the heat capacity curve resembles the Greek letter lambda. This type of transition includes order–disorder transitions in alloys, the onset of ferromagnetism, and the fluid–superfluid transition of liquid helium.

Molecular interpretation 4.1 Second-order phase transitions and λ-transitions One type of second-order transition is associated with a change in symmetry of the crystal structure of a solid. Thus, suppose the arrangement of atoms in a solid is like that represented in Fig. 4.18a, with one dimension (technically, of the unit cell) longer than the other two, which are equal. Such a crystal structure is classified as tetragonal (see Section 20.1). Moreover, suppose the two shorter dimensions increase more than the long dimension when the temperature is raised. There may come a stage when the three dimensions become equal. At that point the crystal has cubic symmetry (Fig. 4.18b), and at higher temperatures it will expand equally in all three directions (because there is no longer any distinction between them). The tetragonal → cubic phase transition has occurred, but as it has not involved a dis continuity in the interaction energy between the atoms or the volume they occupy, the transition is not first-order.

Fig. 4.17 The λ-curve for helium, where the heat capacity rises to infinity. The shape of this curve is the origin of the name λ transition.

Fig. 4.18One version of a second-order phase transition in which (a) a tetragonal phase expands more rapidly in two directions than a third, and hence becomes a cubic phase, which (b) expands uniformly in three directions as the temperature is raised. There is no rearrangement of atoms at the transition temperature, and hence no enthalpy of transition.

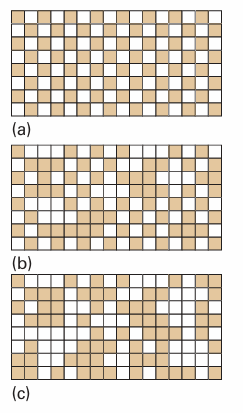

Fig. 4.19An order–disorder transition. (a) At T=0, there is perfect order, with different kinds of atoms occupying alternate sites. (b) As the temperature is increased, atoms exchange locations and islands of each kind of atom form in regions of the solid. Some of the original order survives. (c) At and above the transition temperature, the islands occur at random throughout the sample.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة