Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Syllable Weight and Ambisyllabicity

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P149-C6

2025-03-13

718

Syllable Weight and Ambisyllabicity

Although the first principle of written syllabification (the integrity of prefixes and suffixes) creates severe clashes between written and spoken syllabifications, and will not be commented on further, the second principle, which relates to some orthographic letters and the vowel sounds they stand for, may have some relevance to speakers’ responses to some indeterminate spoken syllabifications.

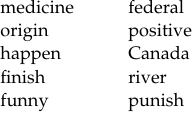

If we ask for the spoken syllabification of the following words we may receive different reactions from native speakers of English.

While several speakers go along with the syllabifications based on the maximum onset principle and give [mε/də/sən], [hæ/pən], [pɑ/zə/təv], etc., some others may not feel very comfortable with such divisions and may suggest the inclusion of the consonants after the vowel in the first syllable as the coda of that syllable. There are some obvious similarities between these words and the ones we discussed in relation to written syllabification above. This is related to the kind of vowel sounds that are represented by the ortho graphic letters a, e, i, o, u. In all these words, the vowel sounds /ε, ɔ, æ, ɪ, Λ/ (from top to bottom of the list of examples) represented by the orthographic letters in question are in the stressed syllables, and the problem is related to what happens to the consonant following that vowel. This issue is directly related to stress and syllable weight. Although stress will be treated in detail, we will briefly deal with some points here that are relevant to the issue we are focusing on.

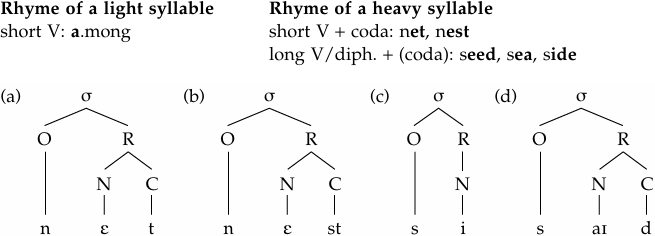

Syllable weight is an important factor in stress assignment in languages. The weight of a syllable is determined by its rhyme structure. In English, a syllable is light if it has a non-branching rhyme (a short vowel and no coda in its rhyme, as in the first syllable of around); it is heavy if it has a branching rhyme (a short vowel followed by a coda (simple or complex), or a long vowel or a diphthong with or without a following coda). This can be shown as follows:

In (a), (b), and (d), the branching rhymes are obvious; in (c), the syllable is heavy because it has a branching nucleus.

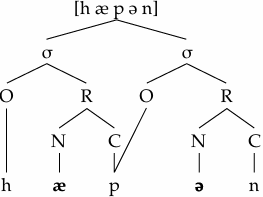

Having made this digression to explain syllable weight, we can conclude that heavy syllables attract stress, and essentially, in English, no stressed syllable may be light. With this information, we are now ready to go back to the problematic cases we considered above. In medicine, happen, finish, etc., we have a conflict between the maximal onset principle and stress. While the maximal onset principle dictates that the first syllables of each of these words be light, the stress that falls on this very syllable contradicts the principle that light syllables cannot receive stress. This is the reason why some speakers are not comfortable with the syllabic divisions in these words. In such cases, linguists invoke the concept of ambisyllabicity, whereby the consonant in question is treated as behaving both as the coda of the preceding syllable and as the onset of the following syllable at the same time. To put it succinctly, we can say that a con sonant that is (part of) a permissible onset (cluster) is ambisyllabic if it occurs immediately after a short vowel /ɪ, ε, æ, Λ, ʊ, ɔ/ɑ/ (i.e. lax vowels plus [ɔ/ɑ]) that forms the nucleus of a stressed syllable.

We can represent this as follows: This is a consequence of the tendency for a stressed rhyme to be heavy (i.e. branching).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)