Putting It Together

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P117-C5

الجزء والصفحة:

P117-C5

2025-03-10

2025-03-10

574

574

Putting It Together

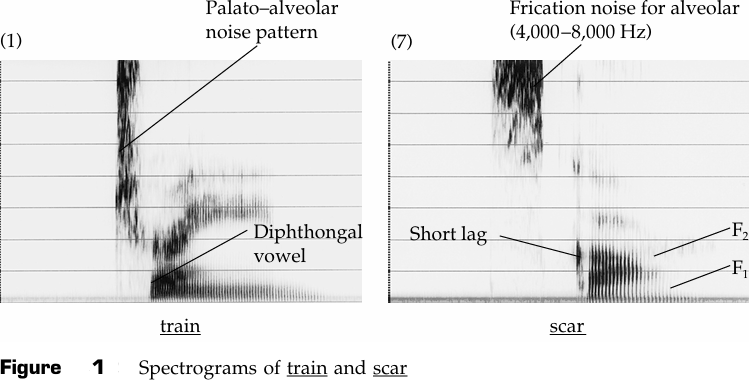

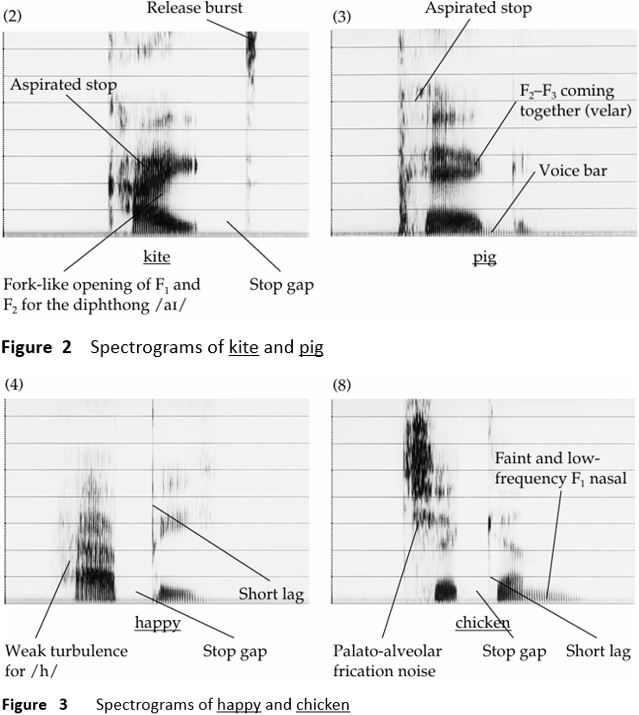

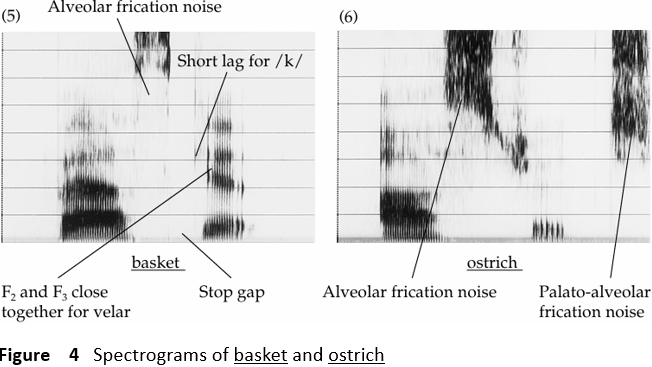

We will review below several characteristics associated with certain sounds that have been discussed by analyzing the spectrograms of eight words: (1) train, (2) kite, (3) pig, (4) happy , (5) basket, (6) ostrich (7) scar, and (8) chicken (see figures 1–4).

The eight words are equally divided into two groups in terms of their number of syllables (four monosyllabics – scar, train, pig, kite– and four disyllabics ostrich, basket, happy, chicken). Thus, looking only at the spectrograms and ignoring the word labels below them, one can separate (1), (2), (3), and (7) as the former (monosyllabics) because of their one vocalic nucleus formants, and isolate (4), (5), (6), and (8) as the disyllabics. Among the monosyllabics, scar is the only one that starts with a sibilant. Although all four words show frication noise turbulence at the beginning, only (1) and (7) are logical candidates for this target, as the noise patterns of (2) and (3) are generalized to all frequencies (a typical pattern for aspirated stops, and thus for pig and kite), rather than the expected concentrated pattern for /s/. This suggests that (1) and (7) are train and scar (see figure 1). Between the two, (7) is a better candidate for scar, as the frication noise is concentrated between 4,000 and 8,000 Hz, typical for alveolars. There is much more supporting evidence for this identification. The frication noise is followed by a stop gap and the following release, /k/, with a short lag (expected of an unaspirated stop), which in turn is followed by a low back vowel (high F1, and a narrow space between F2 and F1) and the r-coloring of the following vowel (the lowering of the third formant). Turning to (1), train, we observe the following: the palato-alveolar nature of the frication noise (i.e. affrication of [tɹ̣]) is evidenced by the 2,000–8,000 Hz range of the noise pattern. Also, we note that the following long and rather diphthongal vowel /e/ (fork-like opening of the formants) and the following faint and very low-frequency F1 nasal fit the expected pattern.

Words (2) and (3) are kite and pig. How do we know which one is which? While both are CVC words that start with aspirated stops and thus cannot be differentiated via this feature in the spectrograms, the features for the remaining parts make the choices rather clear. First of all, the lengths of the vowel nuclei are quite different. In (3), we see a shorter vowel (/ɪ/ of pig). The nucleus of (2) is longer and diphthongal (/aɪ/ of kite starts with a low vowel followed by a high front vowel, and thus, has a fork-like opening). To make things further indubitable, one needs to look at the ‘coming together’ of F2 and F3 right before the stop gap for the coda in (3). As discussed earlier, this is typical of velar stops (/g/ of pig). Both words are produced with their final stops released (note the release burst after the stop gaps). This explains the visible voice bar in /g/ of pig. Thus, (2) is kite and (3) is pig (see figure 2).

Turning to disyllabics, we again start with the frication noise. The only word that starts with a frication noise is chicken, and (8) is the best candidate for this word, as the noise pattern for /tʃ/ is expectedly dark and goes down to 2,000 Hz, which is typical for palato-alveolars. Word (4) shows some frication noise, but the frequencies and the intensity of it are far less than would be expected of /tʃ/; indeed, it is typical of /h/, which suggests that (4) is happy. There are several other indicators that support the identification of these two words: the vowels in the stressed syllables are of very different length, longer /æ/ in happy, and short /ɪ/ in chicken. The portions immediately following the first syllable are expectedly similar (stop gap and short lag release for the unaspirated stops). The differences, however, are clear right after that. The second syllable of (4) has a longer vowel (/i/ of happy), as opposed to the short [ə] of chicken in (8). To add further support to this identification, we can look at the faint and very low-frequency F1 for the nasal ending of chicken (see figure 3).

The two remaining words, basket and ostrich, will have to be matched with spectrograms (5) and (6). This is a rather easy decision for several reasons. Word (6), which has two very obvious frication noises, is ostrich. The first one is /s/, with a typical 4,000–8,000 Hz alveolar pattern, and the second one is /ʧ/, with a lower push typical of palato-alveolars. The same word shows some affrication for [tɹ̣] right after /s/. Still in the same word, the stressed first syllable has a longer vowel, which is low back (note the F1 and F2 ); the second syllable is unstressed (weak intensity and short duration). When we examine (5), basket, we observe the following: unsurprisingly, no visible voice bar for the initial /b/. This is one of the least reliable identifying characteristics of the stops /b, d, g/ except in intervocalic position. The stressed first vowel, /æ/, is expectedly long, and the frication of /s/, though not as strong as that of ostrich, is still clear.

The following sound, /k/, has its stop gap, which is followed by an expected short lag release. The formant transitions for the following vowel (F2 and F3 are close together just after the stop, with a downward transition to a vowel with a high F2) clearly indicate the velar place of articulation. Finally, we note the second syllable with a rather short vowel followed by a stop coda (see figure 4).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة