Fricatives

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P111-C5

الجزء والصفحة:

P111-C5

2025-03-08

2025-03-08

802

802

Fricatives

Fricatives are produced via a narrow constriction in the vocal tract, which creates a turbulent noise (or ‘friction’). Such energy appears on a spectrogram as a scribbly pattern, without regular horizontal or vertical lines. The interval of the frication noise is greater in sibilants /s, z, ʃ, Ʒ/ than in non-sibilants /f, v, θ, ð, h/, and the amplitude for frication noise is 58–68 dB (decibels) for the former, as opposed to 46–52 dB for the latter. The sibilants have places of articulation at or just behind the alveolar ridge. The airstream is funneled smoothly through the groove formed on the surface of the tongue blade and tip. As the air picks up speed it begins to tumble noisily. The tumbling, noisy air jet generally strikes the edge of the upper incisors, or edge of the lower lip, and creates additional edge or spoiler turbulence noise. These noises produced by sibilants are long, strong in amplitude, only a few decibels less than that of vowels, and marked by a rich, high-frequency noise spectrum.

The non-sibilant front fricatives are made with labio-dental and interdental constrictions. The tongue tissue held against the teeth for the dental fricatives creates an abrupt, narrow constriction that generates a weak turbulence noise whose energy is spread to very high frequencies. The noise is so weak that listeners often derive the acoustic clues for identification not from the noise but from the prominent consonant-to-vowel transitions of these sounds.

If, for example, we make a comparison of /f/ as in fin with /θ/ as in thin, we would expect to find the following. Neither sound would create the frication noise as sibilants do (e.g. /s/ or /ʃ/). Although the fricative noises are similar in both, the intensity range is lower in the former (3,000–4,000 Hz) than the latter (7,000–8,000 Hz). What may also help to separate them are the formants of the neighboring vowels: F4 (if visible) is below 4,000 Hz in /f/ and above 4,000 Hz for /θ/. One additional element may be the greater duration of the labio-dental than the interdental fricative. Finally, one might also find a little higher F2 locus for the interdental than for the labio-dental. Given all these small differences, it is not surprising that very few languages demonstrate contrast between these sounds.

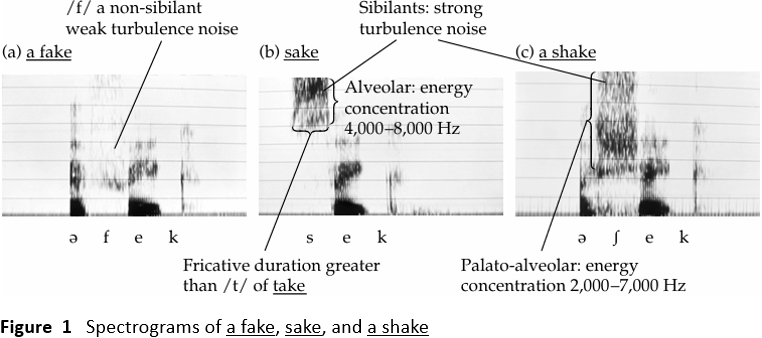

Although we must use subtle clues to separate labio-dentals from inter dentals, the difference between alveolars and palato-alveolars is rather clear. If we compare the /s/ of sin and /ʃ/ of shin, we can easily pinpoint a very clear difference of energy concentration; while the range is something like 4,000–8,000 Hz for the alveolar, it is definitely lower, 2,000–6,500 Hz, for the palato-alveolar. The more forward constriction in the vocal tract produces a smaller vibrating body of air in front of the constriction for the alveolar. This smaller mass of air has a higher resonance frequency than the larger air mass in front of the palato-alveolar constriction used in /ʃ/.

Voiceless fricatives have longer noise segment duration and higher frication noise than their voiced counterparts. The lower frication noise of the voiced fricatives is explained as a result of the total airflow available for producing turbulence at the constriction. Since the glottis opens and closes for vocal cord vibration, the airstream is interrupted, and the friction noise is not as loud in voiced fricatives. Noise that occurs at the beginning of voiceless fricatives is similar to the bursts of /p, t, k/ (i.e. aperiodic high-frequency noise during maximal closure).

Voiced fricatives have formants produced by pulses from the vocal cords, as well as more random energy produced by forcing air through a narrow gap. Since the airstream loses some of its kinetic energy to the vocal cord vibration, the frication noise in these sounds is not as loud as in their voiceless counter-parts. As a result, they have fainter formants.

The articulatory constriction for a voiced fricative is not as tight as for a voice-less fricative, so as to ensure lower supraglottal air pressure while maintaining a sufficiently high transglottal pressure differential to allow the vocal cords to vibrate. This distinction between the relatively loose articulatory constriction for voiced fricatives and the relatively tight constriction for voiceless fricatives is another variable that reduces the amplitude of the fricative noise component of a voiced fricative in comparison to a voiceless fricative. Whatever the cause of the reduction in amplitude of the noise component, it contributes to the perception of a voiced fricative (whether it is really voiced or not).

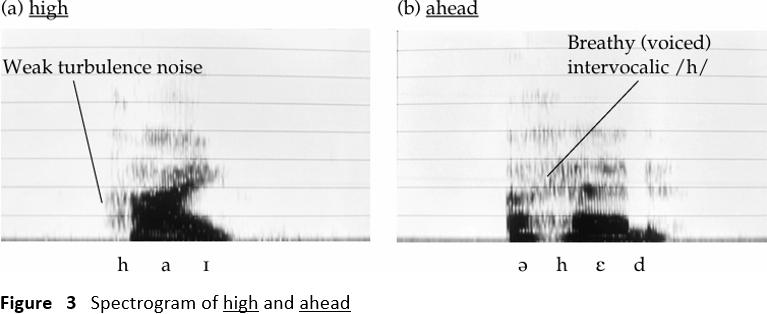

Finally, some comments are in order for /h/, because its status is interpreted differently in different publications. The turbulent noise for this sound, generated at the glottis, is often accompanied by friction near the vocal tract constriction for the adjacent vowel (/h/ is always a single onset). The constriction of the other fricatives involves the articulators (tongue, teeth, lips); the production of /h/, however, leaves these articulators free. Although it is normally treated as a fricative, /h/ is physically an aspiration. The signal for this turbulent noise is very weak, and tends to be voiced (or breathy) intervocalically, as in ahead or behind.

The spectrograms in figure 1 illustrate some of the points made above. Consider the patterns in (a) a fake, (b) sake, and (c) a shake. The difference between (a) and (b) (or (c)) is so obvious that the greater frication noise for sibilants (/s/ or /ʃ/) can be seen effortlessly. When we compare (b) and (c), we observe the frication noise concentrated at different frequencies; approximately 4,000–8,000 Hz for the alveolar /s/, and 2,000–6,000 Hz for the palate-alveolar /ʃ/.

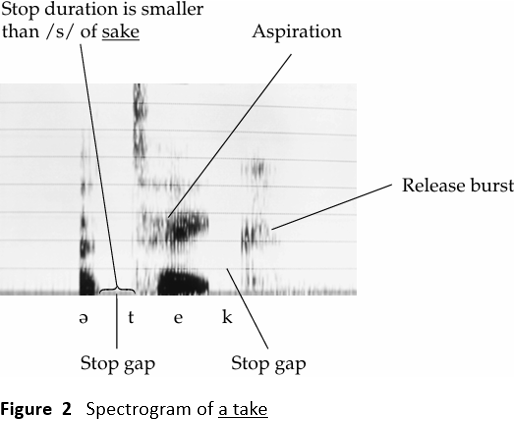

Now, consider the spectrogram for a take (figure 2). This is given to show the durational differences between stops and fricatives. If we compare the duration of /t/ in a take with the duration of /s/ in sake, we can verify the greater duration of fricatives than stops.

Finally, if we consider the spectrograms of high and ahead (figure 3), we can observe the differences in two different phonetic manifestations of /h/.

While it shows as a weak friction in high, it reveals itself as ‘breathy voice’ intervocalically in ahead.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة