Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Vowels

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P102-C5

2025-03-08

1302

Vowels

As shown in the case of [sɪt], vowels have their frequency components grouped into broad horizontal bands, called formants. Different formants characterize different vowels and are the result of the different ways in which the air in the vocal tract vibrates. Every time the vocal cords open and close, there is a pulse of air exiting the lungs, and these pulses act like sharp taps on the air in the vocal tract. The resonance patterns created by the vibration of this body of air are determined by the size and the shape of the vocal tract. In a vowel sound, the air in the vocal tract vibrates at a number of different frequencies simultaneously. These are the resonance frequencies of the particular vocal tract shape. A formant frequency, then, is a bandwidth containing a concentration of energy. Irrespective of the rate of vibration, the air in the vocal tract will continue to resonate at these frequencies as long as the shape of the vocal tract remains the same. The precise acoustic makeup of each sound will differ for each individual speaker, but there are certain core features that make it possible for us to identify the general categories. This is exactly the reason why we can recognize the same vowel produced at different pitches by different individuals. Since vowels are associated with a steady-state articulatory configuration and a steady-state acoustic pattern, they are the simplest sounds to analyze acoustically. Customarily, formants are represented from the lower end of the spectrogram to the upper end. The clearly marked dark bandwidth at the lower end of the spectrogram is the first formant, denoted as F1. The subsequent bands of similarly marked energy locations are the second (F2) and third (F3) formants. Vowel spectra have at least four or five obvious spectral peaks. In general, the frequencies of the first three formants are sufficient to identify the vowels, and the frequencies of F4 and higher formants vary among speakers because they are primarily determined by the shape and size of the speaker’s head, nasal cavity, sinus cavities, etc.

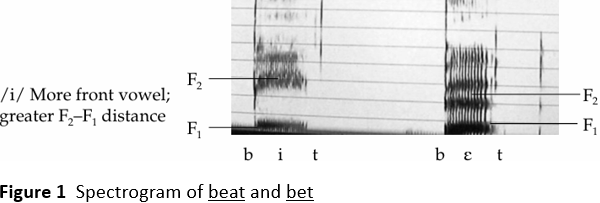

Differences between the vowels of English can be explained in terms of the different locations and widths of the formant frequencies. It is commonly stated that there is a clear relationship between the frequency of the first for mant and the height of the vowel. This happens to be an inverse relationship; high vowels have low first formants, and low vowels have higher first formants. As for the front/back distinction, the frequency of second formants is often mentioned; we see that the frequency of the second formant is much higher in front vowels than in back vowels. However, the correlation between the second formant frequency and the backness of the vowel does not seem to be as solid as the correlation between the first formant frequency and the vowel height. This is primarily due to the fact that rounding in the case of back vowels can affect the frequency of the second formant too. Thus, backness of a vowel can better be related to the difference between F2 frequency and F1 frequency. The simple formula is as follows: A vowel is more front when the difference between F2 frequency and F1 frequency is greater than the same difference for another vowel. Whatever has been said above can be illustrated in the differences between beat and bet (see figure 1).

When we consider the ‘height’ dimension, the expected inverse relationship with the frequency of F1 is very clear. The sound /i/, which is higher than /ε/, has its F1 around 300 Hz, whereas the frequency of F1 of /ε/ is around 550 Hz.

As for the difference between F2 and F1 determining the degree of backness, we can look at the two words again. The resulting numbers from F2 minus F1 frequencies for the vowels /i/ in beat (around 2,150 minus 300 = 1,850), and for /ε/ in bet (around 1,700 minus 550 = 1,150) quite clearly confirm that /i/ is, by nature, more front than /ε/.

To better understand how changes in the vocal tract shape result in different formant frequencies, think of the ‘highest point of the tongue’ dividing the vocal tract into two cavities (front/back). In a movement from the high front vowel /i/ to the low front vowel /æ/, the body of the tongue is retracted, making the front cavity larger (this results in a smaller back cavity). Since the resonating frequency is higher for the smaller vibrating cavity than the larger one, such a movement will have the effect of lowering the resonating frequency of the front cavity (the cavity that has become larger), and increasing the frequency of the back cavity (the cavity that has become smaller). If we think that the F1 frequency is representative of the back cavity, and the F2 frequency is representative of the front cavity, we can understand how the changes in the vocal tract shape can result in the changes in formant frequencies. Thus, there is a gradual increase in F1 frequency as we move from /i/ to /ɪ/ to /ε/ to /æ/.

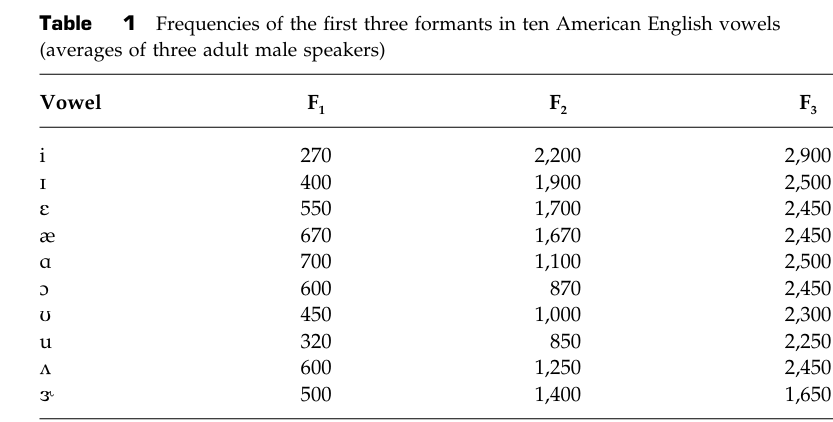

A similar argument can be given to explain the lowering of both F1 and F2 frequencies as we move from /a/ to /u/. As the tongue root is raised toward higher back vowels, the back cavity enlarges, resulting in the lowering of the frequency of F1 . Also, the highest point of the tongue is moving farther back from /a/ to /u/, and this creates a larger front cavity, which results in lowering the frequency of F2 . While the above statements are quite solid for the gradual lowering of F1 frequency for the back series, /ɑ/ to /ɔ/ to /o/ to / ʊ / to /u/, it is not so for the lowering of the frequency of F2 . We consistently see higher F2 frequencies for /ʊ/ than /ɔ/. This is primarily due to the more front production of /ʊ/ than /ɔ/. Table 1 shows the formant frequencies of the first three formants in ten American English vowels. It should be remembered that these values are given as guidelines, not as absolute values. However, they are useful because they indicate the typical vowel patterns in relation to each other. For the front vowels, we see a gradual rise in values for F1 and gradual decrease for F2 . For the back vowels, we see a decrease in the values of F1 and F2 as we move from the lowest back vowel to the highest.

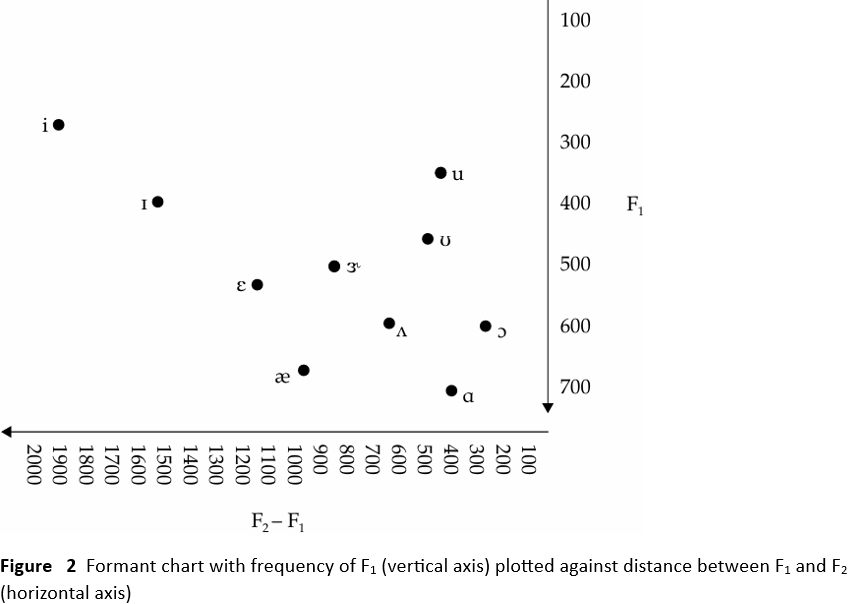

If the frequency of F1 is plotted against the distance between F1 and F2, a chart is obtained that strongly resembles the traditional vowel height charts. This further attest that these diagrams have acoustic correlates (see figure 2).

The frequency of F3 has no simple articulatory correlates, but is useful in the identification of labial consonants and retroflexion. The F3 frequency for the English vowels can be predicted fairly accurately from the frequencies of their F1 and F2. The single exception to this is [ɝ], as in bird. Although its first two formants are very similar to that of /ʊ/, the frequency of its F3 is very low; this will be clear in the discussion of /ɹ̣/ later.

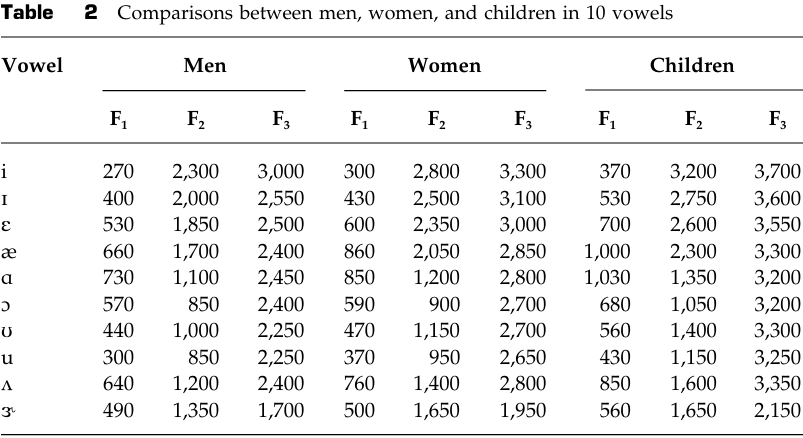

The frequencies given in figure 2 represent male speech. Men’s vowels typically have lower formant frequencies than those of women, and those, in turn, have lower frequencies than those of children. This is due to the size of the vocal tract; the larger the vocal tract, the bigger the bodies of air contained. Since larger bodies of air vibrate more slowly, the formants will have lower frequencies. Table 2 shows the comparison between men, women, and children (often, the F3 cannot be seen in children’s spectrograms). The frequencies are from Peterson and Barney’s (1952) data. The F2 and F3 values are rounded to the nearest 50.

Although the formant patterns are the first and best markers in identifying vowels, ‘duration’ is also a very important parameter. Several factors such as speaking rate, voicing of the adjacent consonant, utterance position, etc. can influence the duration of vowels.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)