Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Acoustics of Vowels and Consonants

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P100-C5

2025-03-08

1188

Acoustics of Vowels and Consonants

The aim here is to present information that will be helpful to teachers of English and/or speech therapists in their assessment and planning of remediation. As such, it does not deal with the details of speech acoustics. Rather, it is intended to supply some basic knowledge concerning the spectrographic analysis of speech. In order to make a reliable assessment, we need an accurate and adequate description of the client’s speech. The affordable software currently available makes such procedures a real possibility both in therapy centers and in classrooms. Since speech that requires remediation reveals patterns that are different from the ‘norm’ (average speaker), the professional who works with remediation may compare the speech of the client to the ‘norm’ to determine the amount of deviation. Speech spectrograms or ‘voice prints’, as many people refer to them, are a very convenient means of displaying the acoustic characteristics of speech in a compact form. Learning to interpret them is also relatively easy with practice. The spectrographic data can be utilized to monitor the changes in remediation and can guide the practitioner in adjusting the remediation plan.

Before we begin a spectrographic description of speech, we need to alert the reader to the following important points. Firstly, while spectrograms provide detailed information about several aspects of speech and can be very helpful in assessment and remediation, it should be noted that not all acoustically distinct phenomena are perceptually distinct. Thus, the practitioner must be able to pinpoint the information in the spectrographic data that is pertinent for a particular case. It is also important to emphasize the fact that perceptual cues interact with each other, and often, the coexistence of several cues is required to reliably identify an opposition with respect to a single feature, such as height or backness of vowels. Secondly, it is important to emphasize that there are inherent problems associated with recognizing words from acoustic information in a spectrogram. In addition to the expected differences because of inter and intra-talker variations, two other issues – ‘linearity’ and ‘invariance’ – are particularly relevant. Although in our phonetic transcriptions we represent the sounds in a linear fashion, this is simply an abstraction. Speech articulations typically overlap each other in time, and result in sound patterns that are in transition much of the time. The boundaries are blurred and the individual sounds can lose some of their distinctive characteristics. Thus, one should not expect that sounds be linearly mapped on to spectrographic displays. Also, characteristics of a given sound change in different phonetic environments (e.g. the nature of adjacent segments, the length of the word, position of the word in a phrase, stress, rate of speech, and so on), and consequently, one should not assume that sounds exhibit invariant characteristics in all contexts.

Production of every sound sets a body of air in vibration. Two factors influence the sounds produced. One of these is the size and the shape of the air. When a short and narrow body of air vibrates, it results in a higher pitch than a body of air that is longer and wider. The other factor is related to the intensity of the sound. The wave forms created by these differences may result in simple (periodic) or complex (aperiodic) patterns, the former showing regular vibrations, and the latter resulting in turbulent patterns. The sound source for vowels is always periodic. For consonants, it may be periodic (glides, nasals) or aperiodic (fricatives), determined by the narrowness of the consonantal constriction. Too much narrowing results in turbulent airflow.

The three acoustic properties of speech sounds are frequency, time, and amplitude.

• Frequency: Frequency relates to the individual pulsations produced by the vocal cord vibrations for a unit of time. The rate of vibration depends on the length, thickness, and tension of the cords, and thus is different for child, adult male, and female speech. A speech sound contains two types of frequencies. The first, fundamental frequency (f0), relates to vocal cord function and reflects the rate of vocal cord vibration during phonation (pitch). The other, formant frequency, relates to vocal tract configuration.

• Time: Time as a property of speech sounds reflects the duration of a given sound. For example, the duration of an alveolar fricative such as /s/ is greater than the corresponding alveolar stop /t/.

• Amplitude: The amplitude of a sound refers to the amount of subglottal (beneath the vocal cords) air pressure.

These three acoustic properties can be analyzed in a spectrographic display. A spectrogram analyzes a speech wave into its frequency components and shows variation in the frequency components of a sound as a function of time. This allows us to see more detail regarding the articulation of the sounds. On a spectrogram, time is represented by the horizontal axis and given in milliseconds (ms). The vertical axis represents the frequency, which is the acoustic characteristic expressed in cycles per second, or Hz. Each horizontal line on this axis indicates 1,000 Hz (or 1 kHz). The intensity (amplitude) is marked by the darkness of the bands; the greater the intensity of the sound energy present at a given time and frequency, the darker will be the mark at the corresponding point on the screen/printout.

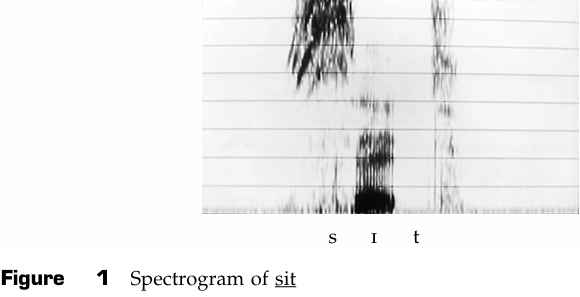

If we look at the spectrogram of the monosyllabic word in figure 1, we can make the following observations. The vowel portion of the word, /ɪ/, contains a series of thin vertical lines (striations) whose darkness varies with loudness. These lines represent the vocal cord vibrations. The space between the lines is in inverse relationship with the fundamental frequency (pitch), given in Hz. For example, with a fundamental frequency of 220 Hz (typical for the female voice), the vertical lines indicating voicing will be 1/220 second, or 4.5 ms, apart in time. The same vowel, with a fundamental frequency of 125 Hz (typical for the male voice), will have its vertical lines 8 ms apart in time. The vowel portion also shows very clear horizontal dark bands. These are the resonance frequencies, called formants. The portion before the vowel /ɪ/ represents the fricative /s/ with its high-amplitude frication noise in the higher frequencies. The portion after the vowel represents the stop /t/. This is shown with a gap, which is the closure portion for /t/, followed by a vertical spike indicating the release of the final /t/. Each of these points will be made more explicit when we examine the spectrograms of different classes of sounds.

Adjustment of the spectrograph can create two different kinds of spectrograms. Broad-band spectrograms have good time resolution, but blur frequency. Narrow-band spectrograms, although they are not as clear on the time dimension, have good resolution for frequency, and are generally the ones we see in books and manuals.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)