Fricatives

English has nine fricative phonemes occupying five places of articulation. Eight of these fricatives are pairwise matching in voiceless/voiced for labio-dental /f, v/, inter-dental /θ,ð/, alveolar /s, z/, and palato-alveolar /ʃ,Ʒ/ places of articulation. The remaining /h/ is a voiceless glottal fricative.

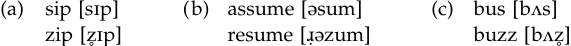

Although the labels ‘voiceless’/‘voiced’ are commonly used to separate certain fricatives, as with stops, the situation of voicing needs to be looked at carefully. The picture presented by the voiced fricatives echoes what we saw in stops; they are fully voiced only in intervocalic position, and partially voiced in initial and final positions.

Thus, among the three words with a voiced alveolar fricative, only the word medial /z/ in resume is fully voiced. Because of this, as with the stops, several phoneticians prefer the terms ‘fortis vs. lenis’ for the voiceless vs. voiced distinction. The fortis fricatives are produced with louder friction noise than their lenis counterparts.

There are other parallels between fricatives and stops. The length of the preceding vowel or sonorant consonant is dependent on the following fricative. Thus, the first member of each of the following pairs has a longer vowel/ sonorant than the second member, as it is followed by a lenis (voiced) fricative:

save [sev] – safe [sef], fens [fεnz] – fence [fεns], shelve [ʃεlv] – shelf [ʃεlf]

As with stops, when a word ends in a fricative and the next word starts with the same fricative, we get one longer narrowing of the vocal tract, as in the one long /s/ in tennis socks [tεnɪs:ɑks] and a long /f/ in half full [hæf:ʊl].

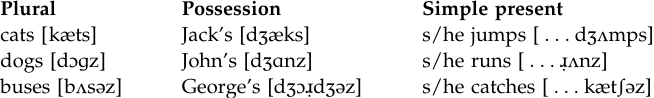

A subgroup of fricatives (alveolars, /s, z/, and palato-alveolars /ʃ,Ʒ/), that are known as ‘sibilants’ are very important for certain regularities in English phonology. These fricatives are produced with a narrow longitudinal groove on the upper surface of the tongue; acoustically, they are identified by noise of relatively high intensity (hissing, hushing noise). In the formation of the regular noun plurals, third person possessive marking, and marking of the third person verb ending in the simple present, sibilants play an important role. In all these events, English has three possible markings, [s], [z], and [əz], as shown in the following:

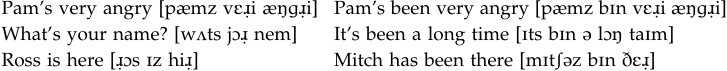

All the above can be accounted for by stating one rule: if the last sound of the singular noun (in the left column), possessor (in the middle column), or verb (in the right column) is a sibilant (affricates /ʧ/ and /ʤ/ are sibilants because they have in them the sibilant fricatives /ʃ/ and /Ʒ/ respectively), then the ending is [əz]; if the last sound is not a sibilant, then the ending is either a [s] or a [z], and this is determined by its voicing. This pattern repeats itself in the contractions with “is” and “has” in connected speech.

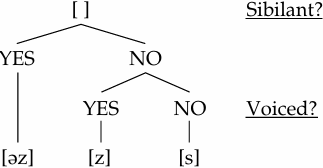

We can show all these in the following tree diagram.

Last sound before the ending

Apart from these characteristics that are general to the fricatives, there are other points worth making for certain fricatives. To start with, palate-alveolar fricatives /ʃ,Ʒ/ differ from the others by having an appreciable lip rounding (labialization). Another pair, alveolars /s, z/, echoing the alveolar stops, may undergo palatalization and turn into [ʃ,Ʒ] respectively, when they occur before the palatal glide /j/. Commonly heard forms such as [aɪmɪʃju] (I miss you), [ðɪʃjiɹ̣] (this year), [aɪpliƷju] (I please you), [huƷjʊɹ̣ bɑs] (who’s your boss?) demonstrate this clearly. Thus, we can put together the behavior of /t, d, s, z/ and state that the alveolar obstruents of English become palato alveolar when followed by a word that starts with the palatal glide /j/ (since there are no palato-alveolar stops in English, the replacements are affricates for /t, d/).

Interdental fricatives /θ, ð/ may undergo the elision process (i.e. they may be left out) when they occur before the alveolar fricatives /s, z/, as exemplified by clothes [kloz], months [mΛns].

Certain fricatives are subject to some distributional restrictions. Firstly, the voiced palato-alveolar /Ʒ/, although it is well established in medial position (e.g. vision [vɪʒən], measure [mεʒɚ]), is not found in word-initial position. Very few seemingly contradictory cases are found in loan words in the speech of only a limited number of speakers (e.g. genre [Ʒɑnɹ̣ə]). The standing of / Ʒ / in f inal position is better established, although one can still observe several fluctuating forms, such as massage [məsɑƷ /məsɑʤ], beige [beƷ /beʤ], garage [gəɹ̣ɑʒ /gəɹ̣ɑʤ] ([gæɹ̣ɪʤ] in BE).

The other fricative that has a defective distribution is the glottal /h/, which can only appear in syllable-initial (never syllable-final) position. This sound is different from the other voiceless fricatives, as the source of the noise is not air being forced through a narrow gap. The origin of /h/ is deep within the vocal tract, and the turbulence is caused by the movement of air across the surfaces of the vocal tract. Also worth mentioning is its voicing status; while it is voiceless word-initially, as in home [hom], his [hɪz], etc., it is pronounced with breathy voice intervocalically, as in ahead, behind, and behave.

The distribution of the voiced interdental fricative /ð/ may also deserve some comment in that, in initial position, it is restricted to grammatical morphemes. It is important to note that although we have fewer than twenty words that begin with this sound (the case forms of the personal pronouns they and thou, the definite article the, demonstrative pronouns such as this, that, and so on, and a handful of adverbs such as then, thus), these are words of high frequency in use.

Finally, we should mention the process whereby unstressed initial /ð/ in words such as the, this, that becomes assimilated (with or without complete assimilation) to previous alveolar consonants (e.g. what the heck [wɑt̪d̪əhεk], run the course [ɹ̣Λn:əkɔɹ̣s], till they see [tɪl:esi], how’s the dog? [haʊz:ədɔg], takes them [teks:əm]).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة