Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Synchronic arbitrariness and diachronic transparency The problem

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P264-C6

2024-12-31

1042

Synchronic arbitrariness and diachronic transparency

The problem

There is one last apparent problem for [r]-Insertion, which I have not addressed so far, but which is frequently cited as the knock-down argument against it by proponents of alternative analyses: this involves apparent arbitrariness. Harris (1994: 246-7) succinctly expresses the issue in his claim that [r]-Insertion

is potentially arbitrary in two respects. First, the process itself must be considered arbitrary, unless grounds can be provided for assuming that it must be r that is inserted rather than any other randomly selectable sound ... There is no obvious local source in the surrounding vowels ... There is another respect in which R-Epenthesis is in need of justification. Why should it take place in the context it does, between vowels as long as the first is non-high? Would we have been surprised if it had applied in any other environment?

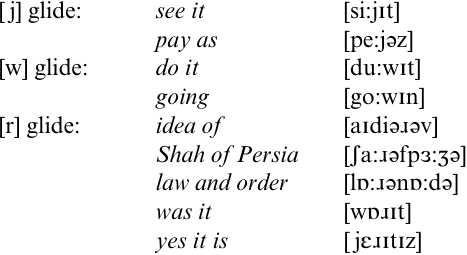

There have been attempts to establish a non-arbitrary conditioning context for [r]. Broadbent (1991) presents an element-based account of [r] in non-rhotic varieties, concentrating mainly on data from West York shire, where intrusive [r] is not stigmatized, and is therefore freely and productively produced, without the variable suppression found in RP. Broadbent observes that [r] is used as a hiatus breaker, compares it with the appearance of [j] and [w] in similar intervocalic contexts, and analyses all three as instantiations of a general process of glide formation. This is not strictly an insertion rule, but involves the spreading of some property of the preceding vowel to an adjacent empty onset to produce a surface glide: this gives [j] after high and mid long front vowels, [w] after high and mid long back vowels, and [r] after those other non-high vowels which can occur word-finally, namely [a: ɒ: ə ε з: ɒ] (1).

(1)

Because Broadbent's approach involves spreading rather than insertion, it can be incorporated into a declarative model. It also formalizes an insight a number of phonologists have used in accounting for the restricted distribution of intrusive [r], by invoking the characteristics of the preceding vowel. For instance, Johansson (1973) argues that /ɑ: ɔ:/ are schwa-final, and that schwa is the common factor which triggers [r]-Insertion (although this would not help with the rather different set of West Yorkshire trigger vowels), while McCarthy (1991) analyses all non-low long vowels as glide final, and claims that this glide blocks [r]-Insertion (although again this may not generalize to other varieties). Certainly, glide insertion and [r] must be related; we have already seen that [r] interacts with [j w] and [ʔ] formation, and also with other phonological processes such as [h]-dropping and vowel reduction.

Nonetheless, it seems that Broadbent's approach must be rejected. First, it makes wrong predictions; Broadbent (1991: 296) claims that `systems can have either linking and intrusive r or neither, but linking without intrusive r is not possible.' The data presented above speak against this, since we have seen that some varieties of Southern States USA and South African English do seem to have linking [r] only. It is also hard to see how Broadbent would account for the history of non-rhotic [r] if she predicts that no prior linking stage could have existed.

Secondly, Broadbent's account of spreading is incomplete: it is easy to establish what elements must be spreading to form [j] and [w] (I and U respectively, when these are the heads of preceding vowels), but much less straightforward for [r]. Broadbent attempts to isolate a common factor from the vowels after which [r] surfaces, and identifies the element A; but this is not the head of all relevant vowels. Consequently, although `the simplest assumption to make is that r-formation occurs when A is the head of a relevant segment', this `raises questions regarding the elemental composition of all non-high vowels, and clearly this requires further work' (Broadbent 1991: 299). In other words, Broadbent's account of [r] requires a wholesale reanalysis of the element structure of vowels, which she does not carry out. Finally, Broadbent (1991) gives no further details on how [r] results from A; if A spreads to an empty onset as an operator, as Broadbent assumes, this will produce schwa. In later work (Broadbent 1992), she argues that the correct output will arise if A can `pick up coronality' at some stage of the derivation; but there is no clear source for the coronal element.

Indeed, attempts to connect the features of /r/ to those of preceding, conditioning vowels may be doomed to failure, insofar as English /r/ itself covers so many variant realizations. Despite the best efforts of phoneticians (Lindau 1985) to identify an articulatory or auditory property unifying the class of rhotics, what makes an /r/ an /r/ also remains unclear cross-linguistically. Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996: 245) are forced to conclude that `Although there are several well-defined subsets of sounds (trills, ¯aps, etc.) that are included in the rhotic class, the overall unity of the group seems to rest mostly on the historical connections between these subgroups, and on the choice of the letter ``r'' to represent them all.'

It is hardly surprising that attempts to establish the affinities of /r/ with preceding vowels have proved fruitless, when we cannot even establish satisfactorily why /r/s form a natural class with themselves. This returns us to the accusation of arbitrariness. If anything, Broadbent's work makes matters even worse for [r]-Insertion, since her data from West Yorkshire indicate that the conditioning context may vary from dialect to dialect, and a random and variable set of vowels seems even harder to deal with than a random and fixed one. It is true that some of the West Yorkshire vowels are only realizational variants of the RP set, and that others are included because of the different phonotactic conditions operative in the different dialects; but nonetheless, the sets are distinct. How, then, are we to defend [r]-Insertion by demonstrating why [r] should be the segment inserted, and in these particular environments? Of course, this relates, as Harris points out, to the question of whether vowels affect the following /r/, or whether /r/ affects the preceding vowels. In fact, there is a single, historical solution to this composite problem of why and where [r] should be inserted.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)