Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Alternative analyses McCarthy (1991)

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P250-C6

2024-12-30

1183

Alternative analyses

McCarthy (1991)

McCarthy argues that Eastern Massachusetts linking and intrusive [r], which appear intervocalically, following /ɑ: ɔ: ə/, are unanalysable in a model assuming only deletion or insertion. Instead, McCarthy claims that non-rhotic dialects of English are characterized by the non-directional statement r ~ ∅, which states that [r] alternates with zero. The contexts in which each term appears will be determined by various constraints in the phonology.

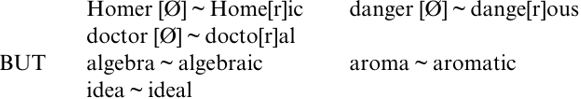

First, McCarthy cites Level 1 alternations such as those in (1), where some derived forms surface with [r], and others without.

(1)

McCarthy proposes distinct underlying forms, such as /howmər/ versus /ælʤəbrə/ to account for the surface patterns. /r/-Deletion then removes /r/ preconsonantally or prepausally in Homer, while [r]-Insertion adds [r] in algebra before a vowel-initial word, as in Algebra[r] is my favorite subject. There is an implied ordering argument here, such that insertion and deletion both operate postlexically, or at least after Level 1. Working on this assumption, we cannot assume either deletion or insertion in both sets of forms, given the presence of [r] in Homeric but its absence from algebraic.

Secondly, McCarthy argues that the behavior of schwa provides evidence for underlying /r/ in certain forms but not others. McCarthy contends that fire, pare, fear, sure, four, flour cannot have underlying final centring diphthongs or triphthongs, because, in Eastern Massachusetts, the schwa frequently deletes when a vowel-initial suffix or word follows: thus fear of, paring, firing are typically, in McCarthy's transcription, [fiyrəv], [peyrɪŋ], [fɑyrɪŋ], although `a trisyllabic pronunciation of words like firing is possible in more monitored speech' (1991: 8). This variable loss of schwa would not in itself present a problem; the difficulty arises because, in a parallel set of words like power, layer, rumba, Nashua, Maria, the final schwa is consistently preserved prevocalically, in contexts like powering [pɑwərɪŋ], layer of [leyərəv], Maria is [məriyərɪz]. To deal with the discrepancies between these two sets of forms, McCarthy argues that we must assume underlying /r/ in cases where schwa need not surface, giving /fiyr/ fear, /fɑyr/ fire; these undergo schwa-epenthesis if /r/ deletes, and presumably also optionally in more formal speech styles, in contexts like fearing, fire it, thus making the centring diphthongs derived segments. On the other hand, power, layer, Maria and so on, where schwa is allegedly always present, must have final underlying schwa and [r]-Insertion prevocalically.

McCarthy's third piece of evidence for the necessity of both insertion and deletion involves function words. He claims that, although linking [r] appears regularly after for, our, they're, their, are, were, neither and so on, intrusive [r] exceptionally fails to surface intervocalically after reduced forms like shoulda, coulda, gonna, gotta, wanna; after did you, should you, as in Did you answer him?; after low-stress to, by, so, as in Quick to add to any problem; after do, as in Why do Albert and you ...?; or after the definite article, as in the apples. McCarthy therefore claims that underlying /r/ must be present in those function words with orthographic , where it will be deleted in codas; however, function words lacking orthographic have no final /r/.

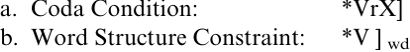

McCarthy further argues (1991: 11) that rule inversion `does not characterize any real mechanism of historical change', on the grounds that the resulting synchronic rule is almost always morphologized: this would not be the case for [r]-Insertion, but if /r/-Deletion is maintained synchronically, as McCarthy claims it is for Eastern Massachusetts in the shape of the non-directional statement of alternation r ~ ∅, there can have been no inversion. The distribution of [r] and zero is determined by the two well-formedness conditions in (2).

(2)

(2a) tells us that the output of r ~ ∅ in codas must be zero, since [r] is banned from this position by the Coda Condition. However, r ~ ∅ in onsets results in [r], because the Word Structure Constraint in (2b) prohibits word-final vowels: it will therefore come into operation at the end of Level 1, when the category Word becomes available. It will only operate after /ɑ: ɔ: ə/ because McCarthy analyses diphthongs and non low long vowels as glide-final; and will not apply to function words, which are not of the category Word, and hence cannot attract intrusive [r]. Postlexically, underlying /r/ and derived [r] will either be resyllabified into an onset, or deleted.

McCarthy therefore claims to have demonstrated that both insertion and deletion processes, or at least a symmetrical statement subsuming both, are necessary in present-day non-rhotic varieties to account for the facts of linking and intrusive [r]. However, his analysis is not conclusive. First, his argument that no historical rule inversion has taken place is not entirely supported by the facts. Notably, McCarthy explicitly proposes underlying /r/ only in forms which surface with non-prevocalic schwa: the Level 1 cases like Homer, danger, doctor have final schwa; so, naturally, do the examples illustrating supposed schwa-epenthesis, such as fire, rear, pare; and so do the reduced function words, including gonna, wanna, to, the. We must assume that historical /r/-Deletion caused conclusive loss of underlying /r/ for later generations of speakers in clusters like harp, beard. However, when first proposing the synchronic co-existence of insertion and deletion, McCarthy (1991: 4) notes that `It is still unreasonable to set up distinct underlying representations for spa and spar, so of course there has been some reanalysis, but both rules are required in any case.' McCarthy does not specify what this reanalysis is, although the answer can probably be gleaned from the rest of the paper: since linking [r] in spa[r]is is derived via [r]-Insertion (1991: 12), and since McCarthy is quite clear that `No internal evidence of the kind available to language learners would justify an underlying distinction between spa and spar, which are homophones in all contexts' (1991: 13), we must conclude that spar has lost its underlying /r/ over time, rather than that spa has gained one. Consequently, for final [ɑ: ɔ:] words, the equivalent of rule inversion has indeed taken place: earlier deletion has become present-day insertion. Note, however, that spa begins as surface-true /spɑ:/, has final [r] inserted at the end of Level 1, and, if no following onset is available for resyllabification, then has the [r] deleted postlexically. Such Duke of York derivations are incompatible with a concrete phonology.

If underlying final /r/, and co-existing deletion and insertion, are relevant only to words with schwa, then McCarthy's case against historical rule inversion is not entirely solid. Moreover, his objection to this alleged change on the grounds that the resulting rule is morphologized does not hold for certain examples not included in Vennemann (1972), including the Scottish Vowel Length Rule, to which we shall return in 6.6. SVLR began as a neutralizing change lengthening short vowels before /r/, voiced fricatives and boundaries, and shortening long ones in all other contexts, but now lengthens tense vowels before /r/, voiced fricatives and boundaries, having done away with the earlier underlying vowel length distinction. It is only `morphologized' in the sense that ] is included in its structural description; this is hardly surprising given that rule inversion seems generally to correspond in Lexical Phonological terms to a progression from postlexical to lexical rule application, and one characteristic of lexical rules is their reference to morphological information. It is understandable that linguists should be sceptical of Standard Generative notions like rule inversion: but this seems to be a case where a Standard Generative suggestion deserves sympathetic attention.

A second difficulty concerns the change of directional r → ∅ to symmetrical r ~ ∅ in non-rhotic varieties. McCarthy treats this as a straightforward generalization, and claims that it accounts for the innovation of intrusive [r]. But if some schwa-words retained final under lying /r/ while others lost it, what commonality might learners perceive in order to motivate [r]-intrusion? Alternatively, do the underliers change in all schwa cases except the Level 1 derived forms, the fire, pare set and function words like for, or, neither, where there is explicit evidence (according to McCarthy) for the retention of underlying historical /r/? Even here, it is not clear that the evidence is strong enough: would a (statistically calculable, but not categorical) difference in the absence of schwa be sufficient for speakers to set up underlying /r/ in pare but schwa in power? It looks suspiciously as if McCarthy's account of the history goes through only on the assumption of rule inversion ± which he rejects.

Let us return now to the three types of evidence adduced by McCarthy for the maintenance of both insertion and deletion. Recall first that McCarthy posits underlying /r/ in Homer, danger, doctor: this is then deleted prepausally and preconsonantally, but surfaces before vowels, including vowel-initial suffixes, giving Level 1 derived Home[r]ic, dange[r]ous, docto[r]al. On the other hand, algebra, aroma, idea must lack underlying /r/, since no [r] surfaces in Level 1 derived algebraic, aromatic, ideal. Clearly, this suggests that neither deletion nor insertion alone can account for these data.

However, these data fit neatly into the [r]-Insertion account developed above, which would predict linking [r] intervocalically in doctoral, dangerous, but not in underived doctor, danger (unless a vowel-initial word follows). There is one apparent difficulty, which involves Vowel

Shift: Pullum (1974: 90) argues that severe ~ severity could not be generated from a common underlier via an [r]-Insertion rule. In fact, a common underlier can be assumed: following my usual assumptions on constructing underlying forms, it must be /səviə/. The context for [r] Insertion will then be satisfied by the addition of the-ity suffix on Level 1, which creates a /ə/-V hiatus. Obviously, Pullum is worried by the derivation of [εr] from /iə/ in severity; but this is also manageable in my version of Vowel Shift. Thus, for instance, divine has the underlier /dəvaɪn/; in divinity, the addition of-ity triggers Trisyllabic Laxing. For diphthongs, this process is assumed to remove the second element and lax and/or shorten the first, giving [æ], which undergoes the Lax Vowel Shift Rule to [ɪ] (a parallel analysis applies for the reduce ~ reduction alternation). Since the centring diphthongs are also falling diphthongs, the foregoing analysis can be extended to them: so, when-ity is added to severe /səviə/, Trisyllabic Laxing will produce [ɪ], which will then regularly undergo Lax Vowel Shift to [ε], the appropriate surface form. Clearly, [r]-Insertion must precede Trisyllabic Laxing in such cases, and must therefore apply on Level 1, so that all its effects cannot be derived from McCarthy's Word Structure Constraint, which becomes relevant only at the output of Level 1.

Level 1 linking [r] in doctoral, dangerous, severity can therefore be derived quite straightforwardly using only [r]-Insertion. Of course, McCarthy proposes underlying /r/ in these cases to distinguish them from the algebra, aroma, idea class; so the real challenge is to account for the latter. McCarthy suggests one way of achieving this: in his view, these latter forms lack underlying /r/, but have final [r] added by [r]-Insertion, acting on the instructions of the Word Structure Constraint, at the end of Level 1. It will then be deleted non-prevocalically at the postlexical level, creating another Duke of York derivation. In algebraic, the tensing rules will have produced /ey]ɪ/), not an environment for [r]-Insertion. Likewise, if all Level 1 morphology has operated before the Word Structure Constraint comes into play, forms like ideal and aromatic will not be receptive to [r]-Insertion, since in ideal the [r] would have to appear in the inappropriate context V ̶ C, while in aromatic, a [t] is present in the `[r] slot'.

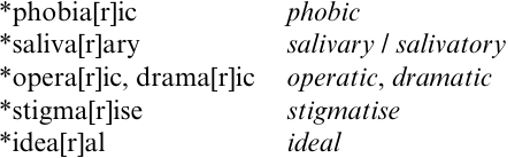

Although [r]-Insertion must precede Trisyllabic Laxing on Level 1 to derive severity, it could equally follow the various tensing rules on the same Level. However, there is another, potentially more satisfactory approach, which also accounts for the apparently unprovoked appearance of [t] in operatic, aromatic, Asiatic, dramatic, and the shortened shape of ideal. McCarthy does not discuss these irregular affixes, and we must conclude that he regards them as variants of the Level 1-ic,-al suffixes. However, the conditions on these variants are hard to grasp: how do we state a restriction which effectively only allows the tic allomorph when intrusive [r] would otherwise surface? Some examples are given in (3); the hypothetical [r] forms which `should' surface are on the left, and the actually occurring derived forms on the right.

(3)

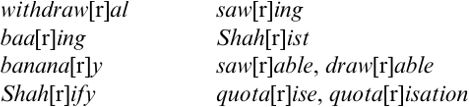

While the doctoral, dangerous, severity forms are regularly derived and relatively productive, the forms in (3) show variable clipping or other extraneous consonants, and are unproductive and isolated. It may well be, then, that these are not synchronically derived, but are instead learned, stored forms: the blocking of [r]-Insertion here then ceases to be a synchronic issue, and becomes a diachronic one. Datings in the OED reveal that the first attestations of the forms in (3) are invariably early, and almost all precede our first evidence for intrusive [r] in the late eighteenth century; hence, these forms date from a period when intrusive [r] was not yet available as a hiatus breaker. For instance, dramatic is attested in 1589; operatic, which the OED assumes to be formed analogically on the basis of dramatic, in 1749; salivatory from 1699 and salivary from 1709; and stigmatize from 1585. More recent or more regular and productive formations, like those in (4), can indeed appear with [r], supporting the hypothesis that its absence from the cases in (3) reflects historical pre-emption by forms derived by varying strategies and now stored.

(4)

McCarthy's second problematic set of data, involving variable absence of schwa, is equally tractable. Recall that McCarthy posits underlying /r/ in forms like fear, pare, fire, but not in layer, power, rumba, Nashua, Maria, to account for the fact that schwa always surfaces before [r] in the second set (in layering, Maria[r]is), but very infrequently in the first (in firing, fear of). However, the fact that firing, fear of can be trisyllabic in more formal speech surely argues for underlying schwa, which would then be deleted in fast or casual speech, rather than schwa epenthesis in formal styles. One might then propose underlying schwa and no under lying /r/ in all of fear, fire, pare, layer, power, Maria and the rest; the now-familiar rule of [r]-Insertion; and a late, optional process of schwa deletion. Of course, we must still explain why schwa deletes so much more frequently in pare than in power. For one thing, pare and power, even when both are pronounced with schwa, are structurally distinct: in pare, schwa forms the offglide of a diphthong and is therefore tautosyllabic with the preceding vowel, while in power, schwa and /aʊ/ are heterosyllabic. Interestingly, in RP, smoothing of the centring diphthongs /εə/, /ɔə/, /ʊə/ to [ε:], [ɔ:] is common, but the reduction of more complex triphthongal /aɪə/, /aʊə/ to [aə] or [ɑ:] (as in fire, flour) occurs even more frequently, supporting the idea that a simplification of complex rhymes may be the main motivation. Similarly, in RP schwa also does not delete in rumba, Nashua or Maria, but very frequently does in [pɑ:rɪŋ] powering, [lε:rɪŋ], layering, where the stem containing the erstwhile schwa is still unambiguous without it: Marie and Maria, however, may be quite different people, and goodness knows what a rumb is (apart from a form violating English phonotactics on account of its final cluster).

Finally, we return to the function words, which seem to attract linking but not intrusive [r], so that McCarthy posits underlying /r/ in for, our, were, neither, but not in wanna, to, do, the. In an [r]-Insertion account, the first set will lack underlying /r/, and have linking [r] regularly inserted, while the remaining function words might be marked as exceptional to [r]-Insertion (since, as McCarthy notes, function words are frequently exceptional to generalizations and rules affecting `real' words). Alternatively, Carr (1991: 51) suggests that [r]-Insertion across word boundaries is blocked by postlexically formed foot structures, and cannot cross the foot boundary in cases like wanna eat. However, none of these solutions is required in another set of non-rhotic dialects, such as many non-RP varieties in England, where wanna eat, gonna ask do attract intrusive [r]; similarly, the examples in (Rule inversion and [r]-Insertion (3)) showed that reduced to, by, you can attract [r] in Norwich and Cockney, for instance. Even in these dialects, do tends not to have following [r], probably because the vowel does not fully reduce to schwa, but retains some of its height and rounding, making a [w] glide more likely. Although the definite article also appears in McCarthy's set of function words, it is not clear that it fits into the category of potential [r] contexts: in the apples, the prevocalic allomorph [ði:] should be selected, and the resulting hiatus will then be broken by [j]. Only if the preconsonantal [ðə] allomorph were chosen would an appropriate context for [r]-Insertion arise: and we have already seen that exactly this pattern is found in speech errors and child language. In short, McCarthy's three sets of data, which he claims necessitate both synchronic deletion and insertion of [r], are in fact quite consistent with an insertion-only account, while McCarthy's own analysis is flawed in several respects. There is nothing here to make us abandon [r]-Insertion; on the contrary, we may have found some extra arguments for it.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)