Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

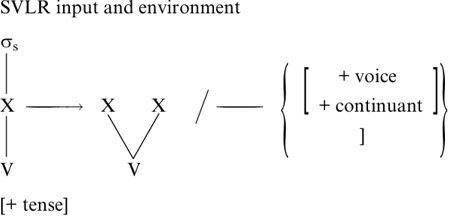

The environment for SVLR

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P189-C4

2024-12-19

1154

The environment for SVLR

If LLL and SVLR do co-exist in SSE and Scots dialects, they must be individually characterized. In fact, each has a distinct input and environment: LLL applies to all vowels before all voiced consonants and word finally (or, perhaps more accurately, pre-pausally), while SVLR is much less general, affecting only a subset of the vowel system, before voiced fricatives, /r/ and ], the bracket used in Lexical Phonology to replace traditional word and morpheme boundary. We established and formulated the input conditions for SVLR, and must now attempt to characterize the environment more satisfactorily. To do so, we must address the question of why vowel lengthening should occur preferentially in these particular SVLR contexts.

In universal terms, the relevant factors determining length seem to be voicing, and the different rates of transition between adjacent vowel and consonant closures: `with stop consonants, the closure transition from a preceding vowel is shorter, since the achievement of a stricture of complete closure does not require the same degree of muscular control as that required for a fricative' (Harris 1985: 121). Harris therefore proposes a consonant scale from voiceless non-continuants at the extreme left, which do not lengthen vowels, to voiced continuants, which most affect the duration of preceding vowels, at the extreme right.

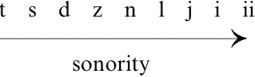

Ewen's (1977) Dependency Phonology formulation of the synchronic SVLR, and Vaiana Taylor's (1974) statement of the historical rule both rely on similar strength or sonority hierarchies. However, Harris (1985: 91) points out a number of problems with this interpretation of SVLR lengthening as `preferential strengthening'. Most importantly, Vaiana Taylor's sonorance scale does not differentiate /l/ from /r/, and excludes nasals (which, according to similar sonority hierarchies proposed by Vennemann and Hooper, for instance, should be intermediate between voiced fricatives and liquids). On Ewen's syllabicity hierarchy, the elements involved in SVLR (i.e. vowels, liquid /r/ and voiced fricatives) similarly form a discontinuous sequence. The prediction of a typical sonority scale of the sort in (1) is therefore that lengthening should affect vowels in the context of nasals and liquids before it affects them in the environment of voiced fricatives, and this is certainly not the case for SVLR.

(1)

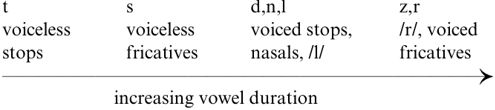

However, Harris's voicing and continuance scale does seem to permit a positioning of nasals and /l/ which accounts for their status as long contexts for LLL but as short contexts for SVLR. Harris (1985: 122) classifies the nasals with the voiced stops on the grounds that `the oral gesture required for nasal stops is the same as that required for oral stops, i.e. an abrupt, ballistic movement appropriate for a stricture of complete closure. This manner of articulation ... favors a shorter duration of preceding vowels. Hence nasals are Aitken's Law ``short'' environments.'

Harris separates the liquids by analyzing /l/ as [- continuant] and /r/ as [+ continuant], citing cross-linguistic evidence that /l/ typically patterns with non-continuant segments. Although Chomsky and Halle (1968) initially classify all liquids as continuants, they recognize this as problematic. As Harris (1985: 123) points out, the difficulty disappears if the articulation of non-continuants is taken to involve a blockage of the airflow along the sagittal plane of the oral tract. This redefinition is now fairly standard, giving a combined voicing and continuancy scale as shown in "Low-Level Lengthening (1)" earlier, repeated as (2).

(2)

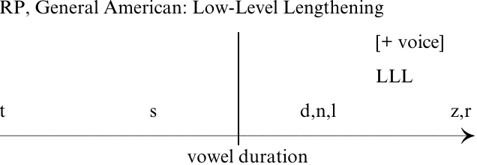

The environments for SVLR and LLL are readily statable in relation to this scale. In RP and GenAm, the one relevant lengthening rule applies progressively before all voiced consonants, both continuants and non-continuants; that is, everywhere to the right of the vertical line in (3), and with even greater length pre-pausally, although the scale has been restricted at present to consonantal environments.

(3)

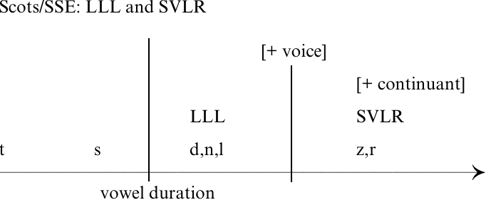

In Scots, this rule also applies, in the same environments, but SVLR also operates before voiced continuants, thus on the right of the right most vertical line in (4).

(4)

It is interesting to note (Nigel Vincent, personal communication) that a similar generalization of allophonic vowel lengthening, but in the opposite direction, is taking place in Modern French, where older speakers have long vowels before the voiced continuants /v z Ʒ ʁ/, giving long-short alternations in pairs like vif (m.) ~ vive (f.) `lively', but younger speakers also have long vowels before voiced stops, as in vague `wave', robe `dress'.

We can now formulate the SVLR environment in feature terms as in (5).

(5)

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)