Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Justifying the S in SVLR

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P160-C4

2024-12-14

1143

Justifying the S in SVLR

If we are to establish SVLR as a Scots-specific phonological rule, we must first challenge Agutter's contention that `the context-dependent vowel length encapsulated in SVLR is not and perhaps never was Scots specific' (1988b: 20). I shall show that SVLR can be defended synchronically as a Scots-specific process; there is also evidence that SVLR was historically introduced only into Scots.

Harris (1985: ch.4) discusses the chequered history of Middle English /ε:/, the vowel of the MEAT class of lexical items. This class, although intact at the beginning of the early Modern English period, had merged in standard dialects by the eighteenth century with the MEET class. Controversy exists, however, over whether the MEAT class earlier merged with the MATE class (5 ME /a:/) before splitting and re merging with Middle English /e:/ at /i:/ (Dobson 1957, Luick 1921). Harris believes that a consideration of some Modern English dialects which retain a three-way contrast of MEET, MEAT and MATE words may shed further light on the dubious history of /ε:/; from our point of view, what is interesting is the strategies which dialects of different areas have implemented to keep these classes of words, with Middle English /ε: e: a:/, distinct.

MEET-MEAT-MATE contrasts persist in many varieties of conservative Hiberno-English (Harris 1985: 232), various rural English dialects (Wells 1982), and some Scots dialects (Catford 1958). Harris discusses several strategies whereby dialects preserve the MEET-MEAT MATE contrasts, including diphthongization; the `leapfrogging' of the reflex of Middle English /a:/ past that of /ε:/; and the use of length contrasts. However, these strategies are not evenly distributed across English and Scots dialects.

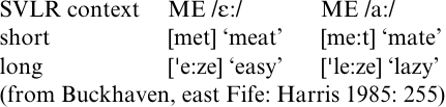

Harris considers five Modern Scots dialects which keep their reflexes of Middle English /ε: e: a:/ distinct ± those of north-east Angus, Kirkcud bright, east Fife, Shetland northern Isles/Yell/Unst, and Shetland main land/Skerries. One of these, Kirkcudbright, is a `core', central Scots dialect with full implementation of SVLR, so that /i e e̟/, the reflexes of Middle English /e: ε: a:/, are all positionally long or short. However, `the other four dialect areas are typical of geographically peripheral areas of Scotland where Aitken's Law has not gone to completion' (Harris 1985: 254). Here, while the /i e/ reflexes of Middle English /e: ε:/ are subject to SVLR, the reflex of Middle English /a:/, which is /ε:/ in north-east Angus and Shetland northern Isles/Yell/Unst and /e:/ in east Fife and Shetland mainland/Skerries, is phonemically long. That is, in east Fife and Shet land mainland/Skerries, the reflexes of Middle English /ε:/ and /a:/ are qualitatively identical. However, SVLR affects one vowel, /e/ /ε:/, while phonemic length remains in /e:/ , /a:/. The length difference is, of course, neutralized in SVLR long contexts, but is sufficient to maintain the contrast elsewhere, as can be seen from (1).

The other three Scots dialects all differentiate Middle English /ε:/ from /a:/ qualitatively, as /e/ versus /e̟/ in Kirkcudbright and /e/ versus /ε:/ in north-east Angus and Shetland northern Isles/Yell/Unst. The latter two dialects use conditioned versus phonemic length as an additional distinguishing strategy.

The significance of this dialect evidence for the status of SVLR becomes apparent from Harris's comparison with five English dialects which also maintain a three-way MEET-MEAT-MATE contrast. In all the English cases, the reflex of Middle English /ε:/ or /a:/ (or both) has diphthongized. In addition, some dialects preserve the original relative heights of these vowels, as in Westmorland, with /iə/ ME /ε:/ and /ea/ Middle English /a:/, while others reverse them; so, Devon and Corn wall has /εi/ Middle English /ε:/ but /e:/ Middle English /a:/. None of the English dialects uses vowel length differences to keep the MEAT MATE-distinction, since they all retain the reflexes of Middle English /e: E: a:/ as phonemically long vowels or diphthongs and, in the absence of SVLR, there is no phonemic versus positionally determined length dichotomy. However, four out of the five Scottish dialects discussed by Harris maintain the MEAT-MATE distinction by exploiting the length difference created by the incomplete operation of SVLR, either as the sole distinguishing factor or along with the preservation of the relative vowel heights. The sole exception is Kirkcudbright, where SVLR has been implemented fully and no phonemically long vowels remain. No Scottish dialect uses the strategy of diphthongization; this is in keeping with the tendency of Modern Scots and SSE long vowels to be realized as long steady-state monophthongs rather than sequences of vowel plus offglide. The geographical skewing of the different strategies employed in maintaining a MEET-MEAT-MATE distinction lends support to the hypothesis that SVLR was introduced diachronically only into Scots.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)