Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Vowels

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

146-4

2024-12-10

1439

Vowels

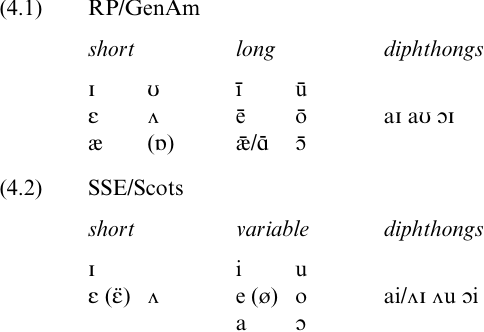

In (4.1), I reproduce the underlying vowel system for RP and GenAm which emerged from the emendations to Halle and Mohanan (1985) in chapters 2 and 3. An outline SSE/Scots system is listed in (4.2). Needless to say, each of these core systems contains a number of option points (often represented as bracketed vowels), and can be taken as temporary shorthand for a set of marginally different daughter systems; for a classification of Scots dialects using a similar system, see Catford (1958).

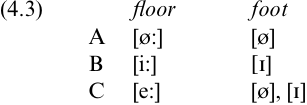

The two vowels bracketed in (4.2), /ø/ and /ε̈/, are very frequently encountered in Scots and occasionally in SSE. /ø/, a mid front rounded vowel, appears dialect-specifically in words like foot, floor, moon and spoon; it is the result of fronting of /o:/ to /ø:/ in Scotland, Northumberland, Cumberland, Durham, North Lancashire and Yorkshire in the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century. Aitken (1977) distinguishes three Modern Scots dialect-specific patterns of realization of earlier Scots /ù:/ (see (4.3)).

The length variation here results from the Scottish Vowel Length Rule, to be considered below. The quality differences seem to reflect variability in whether the /ø:/ vowel raised in the Great Vowel Shift, and the relative chronology of this raising, unrounding and SVLR.

/ε̈/ is more intriguing. Abercrombie (1979) notes that the first person to classify /ε̈/ as distinct from both /ɪ/ and /ε/ was A.J. Aitken, in whose honour it is sometimes called `Aitken's vowel'. It is easy to see why /ε̈/ evaded notice for so long, for various aspects of its quality, origin and distribution (both areal and lexical) remain opaque.

/ε̈/ characteristically occurs in words like bury, devil, earth, clever, jerk, eleven, heaven, next, shepherd, twenty, ever, every, never, seven, whether; however, Winston (1970), who tested a number of subjects from Edin burgh University for the presence and use of /ε̈/, found that although all her informants had contrastive /ε̈/, there was not one word where they all consistently used it. In addition, /ε̈/ has a regionally defined distribution, occurring principally in dialects of the West, the Borders, Perthshire and at least some parts of Edinburgh.

As for the quality of /ε̈/, it is generally negatively defined (Wells 1982: 404):

Where present, /ε̈/ is phonologically and phonetically distinct both from /ɪ/ and from /ε/, and in quality is typically somewhat less open than cardinal 3 and considerably centralized. The opposition can be tested by the triplet river vs. never vs. sever. If never rhymes neither with river (/ɪ/) nor with sever (/ε/), then it can be assumed to have /ε̈/.

Even less information can be gleaned on the origin of /ε̈/; perhaps the most plausible explanation is offered by Kohler (1964). Kohler notes that, in some Scots dialects, /ε̈/ is used in most of the words where SSE and RP have /ɪ/. He suggests that /ε̈/ was the original short vowel, but that /ɪ/ was later borrowed from English dialects and diffused variably through the same set of words. /ε̈/ tends to survive most consistently and widely in forms like never, shepherd, seven, where English dialects had /ε/ but Scots has /ε̈/ or native /ɪ/ - spellings like <niver> are relevant here.

There are a few other discrepancies between SSE and Scots dialects, some of which we shall return to below. For instance, whereas SSE has [u:] in two, Scots tends to have [e:], [a:] or [ɔ:], reflecting a pre-Great Vowel Shift monophthongization of word-final /ai/ in frequently used lexical items; the resulting /a:/ was then either raised in the Vowel Shift giving modern [e:], or was retained after a labial consonant, which in some areas rounded the vowel. Snow, blow have Scots [ɔ:] rather than SSE [o:], ultimately as a result of twelfth century Long Low Vowel Raising; differential operation of the same sound change in the north and south also gives the characteristic Scots [e] of stane, hame as opposed to RP and SSE stone, home. Finally, the diphthong /au/ is marginal in Scots, since the Great Vowel Shift failed for /u:/ > /au/ in the North, so that /u/ is retained in Scots house, out, cow. /au/ is present only in a few place names like Cowdenbeath, some specifically Scots lexical items like howff and loup, and words with earlier /ɔl/ 4 /ɔu/ 4 /au/ via l-Vocalization, as in gold [gΛud] and knoll [nΛu]. For details of these and other Scots sound changes, see Johnston (1997a).

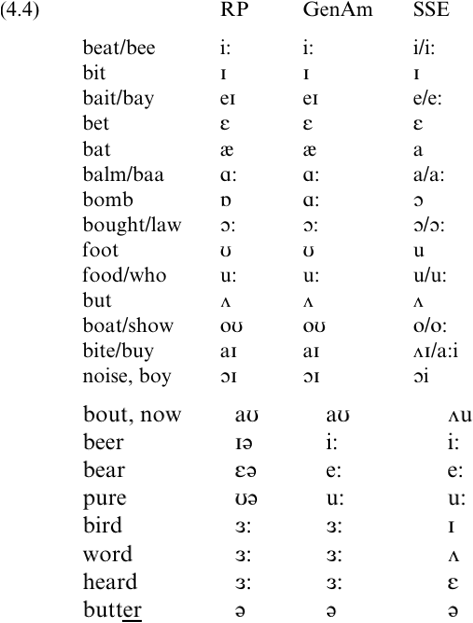

Our main concern here, however, lies in the different patterns of distribution between SSE (and Scots), RP and GenAm vowels shown in (4.4).

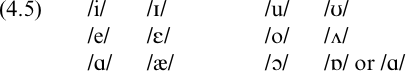

There are several clear differences between the RP and GenAm systems on the one hand, and that of SSE on the other. Minor realizational discrepancies apart, these can be subsumed under one generalization. In RP and GenAm, all those vowels which can appear in stressed open syllables (that is, all vowels except /ɪ ε æ ɒ ʊ Λ ə/) surface consistently as long or diphthongal: Giegerich (1992) analyses these as alternative manifestations of underlying tenseness. A full discussion of the feature [± tense] must be deferred for the moment; let us accept for the moment that RP and GenAm are analyzable in terms of six pairs of vowels, the members of which are qualitatively and quantitatively distinct but of roughly the same height (4.5).

In SSE, this dual distinction of quantity and quality is not operative. Three of the oppositions are entirely lacking, with RP /ɑ/ ~ /æ/, /ɔ/~/ɒ/ and /u/ ~ /ʊ/ each replaced by a single vowel in SSE, conventionally represented as /a/, /ɔ/ and /u/ respectively. There are consequently a number of minimal pairs in RP which become homophonous for Scottish speakers, although Abercrombie (1979: 75±6) points out that more anglicized speakers of SSE may import these oppositions from RP. Typically, the introduction of /u/ ~ /ʊ/ presupposes /ɔ/ ~ /ɒ/, which in turn presupposes /ɑ/ ~ /æ/: the low vowel contrasts are quite common in SSE, especially in Edinburgh, but the /u/ ~ /ʊ/ distinction is very rare and tends to be inconsistently maintained.

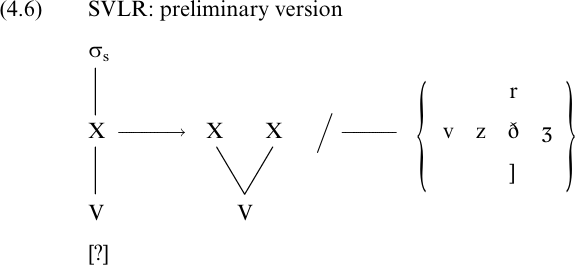

The three remaining vowel pairs, /i/ ~ /ɪ, /e/ ~ /ε/ and /o/ ~ /Λ/, are relevant for Scots and SSE; but the nature of the opposition is different from that in RP and GenAm. Diphthongization in Scots dialects and in SSE is rare, even for the mid vowels /e/ and /o/, with the only surface diphthongs being realizations of the `true' diphthongs /Λɪ/ ~ /ai/, /au/ and /ɔi/. I have argued that these should be analyzed as underlyingly diphthongal, and this goes for Scots/SSE as well as RP and GenAm, although the exact nature of their underlying representations for Scots/ SSE will be the subject of some discussion below. Nor does length consistently distinguish the members of these pairs, since quantity in Scots and SSE is largely non-contrastive and context-sensitive; as shown in (4.4), /i e o/ are therefore long only in certain circumstances. The Scottish Vowel Length Rule (Aitken 1981, McMahon 1991, Carr 1992) is the process responsible, and a preliminary version is given in (4.6).

SVLR lengthens a certain set of vowels (to be defined later) when they precede /r/, any voiced fricative, or a bracket - the Lexical Phonological equivalent of a word or morpheme boundary. /i/ will consequently be long in beer, breathe, key, and keyed, but short in keep, wreath, keen and need. For the majority of vowels affected, SVLR simply controls an alternation of length, but for the diphthong /ai/, there is a concomitant change of quality with [Λi] in short and [a:i] in long environments.

We shall focus on SVLR. Evidence from previous discussions and formulations of the process will be used to ascertain precisely what subset of vowels constitutes its input, and what feature specification might characterize that class. Experimental investigations of SVLR will be assessed; these include work by Agutter (1988a, b), who claims that `the context-dependent vowel length encapsulated in SVLR is not, and perhaps never was Scots-specific' (Agutter 1988b: 20). The refutation of this assertion will involve a comparison of SVLR with a related lengthening process which operates in all dialects of English. However, before embarking on a detailed synchronic analysis, we must consider the historical source of SVLR: we shall see that a diachronic perspective is essential, here as in many other cases, to a full understanding of the present day situation.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)