Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Why constraints? Halle and Mohanan (1985)

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

50-2

2024-11-27

1148

Why constraints? Halle and Mohanan (1985)

The most extensive and comprehensive lexicalist account of English vowel phonology currently available is Halle and Mohanan (1985), and my attempts below to constrain the framework and mechanisms of LP will focus on this version of the theory. The critique developed here is applicable also to Mohanan (1986), which shares many of the assumptions of Halle and Mohanan (1985). Although Halle and Mohanan are working within the letter of LP, their analyses frequently fail to cohere with the spirit of the lexicalist enterprise, if we take that spirit to include the reduction of abstractness and the removal of unwarranted machinery and unmotivated derivation. I shall return in detail to the Halle and Mohanan model, considering many of their analyses in depth. For the moment, I intend only to demonstrate that their model cannot be seen as a significant advance over SGP.

First, let us turn to the general architecture of the model. As noted above, the Halle and Mohanan model comprises four lexical strata, as against Kiparsky's (1982) three and Booij and Rubach's (1987) two, as well as one postlexical level. If the number of levels proposed for a language is in principle unbounded, the theory loses any claim to explanatory adequacy, since an analysis would be possible in which each word-formation rule or phonological process were assigned to a separate stratum, or every rule to every stratum. Moreover, allowing random interspersal of cyclic and non-cyclic strata, as Halle and Mohanan also do, further compromises LP in that the operation or suspension of constraints will be purely a matter of stipulation. Nor do they strictly adhere to the four lexical strata they declare; their model also incorporates a so-called Loop, which allows compounded forms derived on their Level 3 to cycle back into Level 2 affixation. Since there is no principled limit to the levels between which loops could be proposed, the way would in principle be open for such morphological interaction between every pair of strata. In Halle and Mohanan's model, the concept of morphological level-ordering is effectively dead in the water.

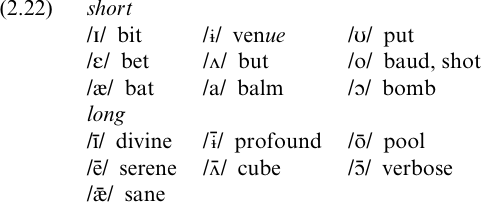

There are similar problems of permissiveness in their specific phonological analyses. Halle and Mohanan are primarily concerned with General American, although they claim the underlying vowel system they propose (see (2.22)) is also appropriate for RP; this assignment of a single underlying phonological system to related dialects was a characteristic of SGP which Halle and Mohanan carry over into LP.

If we were looking for a predominantly surface-true vowel system, we would not find it here. The SPE account of Vowel Shift is retained, with the tense vowels shifting in sane, serene, divine, and free rides in parallel non-alternating plain, mean, pine. A single underlying representation is proposed for the vowel in balm, and one for bomb, although the realizations vary widely across British and American accents, and indeed the two are homophonous for many speakers. Absolute neutralization is rife, with [jū] in cube and [jū] in venue derived from distinct underlying vowels.

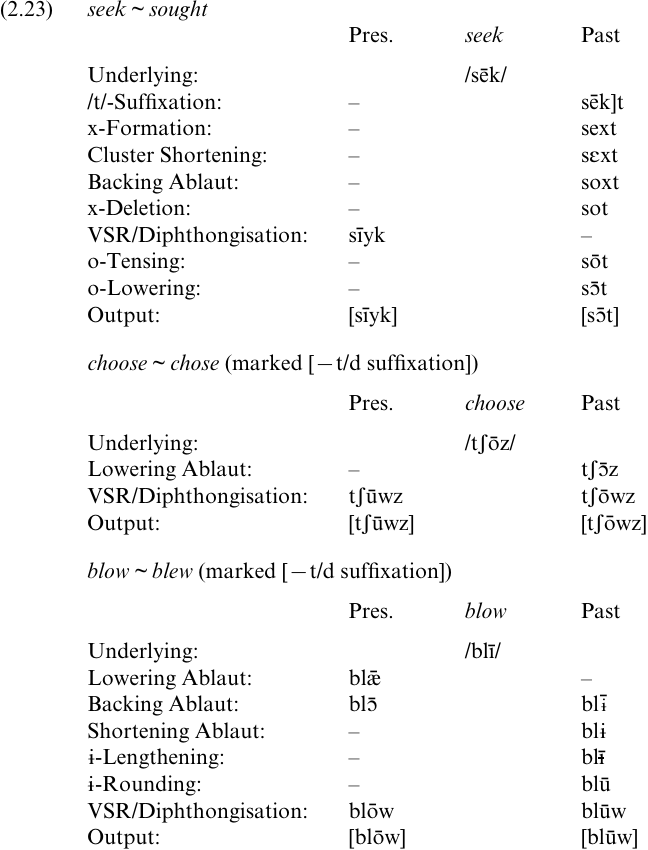

For the moment, I consider only one further example: the Modern English strong verbs. On the principle of `can do, will do' familiar from SPE, Halle and Mohanan elect to derive alternating pairs like seek ~ sought, choose ~ chose and blow ~ blew from single underlying forms. This requires, of course, the whole panoply of SGP derivational techniques, as illustrated in (2.23).

Connoisseurs of untrammelled generative analysis will find all their old favorite tricks here. We have non-surface-true underliers; special diacritic marking; a whole complex of ablaut and related rules which are required only for these strong verbs, and yet are presented as if equivalent to productive processes; abuses of extrinsic ordering involving `lay-by' procedures; and `Duke-of-York' derivations, which involve the production, destruction and re-derivation of the desired output, as in chose.

In the face of examples like these (and there are plenty to choose from), it must be clear that LP is in serious danger of losing sight of its founding aims. Lexical Phonologists are not, of course, alone in their weaknesses here; there is a recurring tendency in phonology to invent constraints or conditions, then see these as some panacea which means entirely unrestrained derivation is somehow all right. Take Brand X, drink anything you like, and you won't have a hangover. Except that 10-to-1 you still will, and Brand X will have wreaked its own havoc on your system in the meantime. And you still behaved like an idiot.

It should go without saying, but doesn't, that constraints are useless unless they are imposed and taken seriously. There is no point in formulating restrictions if we then devote all our intellectual energies to finding ways to defuse and disarm them; as we shall see, the use of underspecification to get round SP, and the ordering of rules on Level 2 to evade SCC are excellent examples of precisely this strategy. Identifying circumstances in which the constraints fail does not occasion congratulations. At best, it is a signal that we must find the underlying principle or factor which explains the non-application of the constraint. We shall see that such explanations may in fact be historical rather than synchronic.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)