Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Modelling sound changes

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

20-1

2024-11-23

1419

Modelling sound changes

We return now more specifically to diachronic evidence. Proponents of some recent phonological models explicitly exclude historical processes from their ambit; Coleman (1995: 363), for instance, working within Declarative Phonology, refuses to consider one of Bromberger and Halle's (1989) arguments for rule ordering because of `its diachronic nature. The relevance of such arguments to synchronic phonology is highly controversial, and thus no basis on which to evaluate the transformational hypothesis.' I reject this curtailment of phonological theory for two reasons. First, more programmatically, theorists should not be able to decide a priori the data for which their models should and should not account. It is natural and inevitable that a model should be proposed initially on the basis of particular data and perhaps data types, but it is central to the work reported below that the model subsequently gains credence from its ability to deal with quite different (and perhaps unexpected) data, and loses credibility to the extent that it fails with respect to other evidence. Secondly, and more pragmatically, no absolute distinction can be made between synchronic and diachronic phonology. Variation is introduced by change, and in turn provides the input to further change; and even if we are describing a synchronic stage, we must unavoidably contend with the relics of past changes and the seeds of future ones. Furthermore, synchronic and diachronic processes have much in common; yesterday's speech error or low-level phonetic process may be today's sound change, and is quite likely to be tomorrow's morphophonemic alternation. And different time-zones cross-cut the domain of any particular language, so discerning exactly where we are in that simplistic typology of yesterday, today and tomorrow is not always straightforward.

To take a slightly different tack, those phonologists working in non-derivational theories are often precisely those most interested in phonological universals. It must be important to test hypotheses involving universals on as wide a range of systems as possible, ideally from genetically, areally and typologically distinct languages, and also dialects, which in time may well diverge into distinct languages. Since variation and change are intimately connected, it seems unreasonable to accept the input and output for sound change, but to sideline or ignore the changes themselves. Similarly, if we want to explain phonological processes, and perhaps more accurately, to define and delimit possible process types, then it is extremely important to include sound changes: why should comparison across space be legitimate but not across time, in the search for universals? This is particularly incoherent given that the types of processes to be found in change overlap substantially with those operating to create synchronic alternations. That is to say, a synchronic fast speech process may become a categorical insertion or deletion change cross-generationally; or an automatic, phonetically motivated process can be phonologised, perhaps in different ways in different dialects, to give a synchronic phonological rule; we shall see examples of such interaction later. However, this does not mean that we can automatically subsume historical processes in the set of synchronic ones: even if a theory can model a synchronic process in an enlightening way, it is by no means a foregone conclusion that it can similarly deal with a historical analogue of the process.

With this in mind, we shall now move on to see how two allegedly non derivational theories, Government Phonology and Optimality Theory, fare when confronted with certain generic types of sound change.

We turn first to Government Phonology (Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud 1985, 1990; Harris 1990, 1992), in which phonology is taken to consist of a system of universal principles, and a set of parameters set on a language-specific basis. There are no phonological rules. Segments are composed of elements, which are autonomous and independently interpretable (Durand and Katamba (eds.) 1995). The defining property of each element is a feature with a marked value, the hot feature: this is the only component contributed by the operator, as opposed to the head, in fusion. The only element lacking a hot feature is the cold vowel. Government itself is a relationship holding between adjacent positions in a phonological string, and holds at three different levels of analysis:

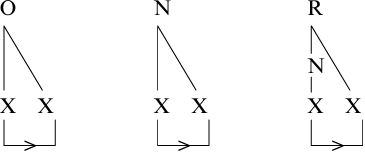

(1) within the constituents onset, nucleus and rhyme, where government is strictly local and left to right:

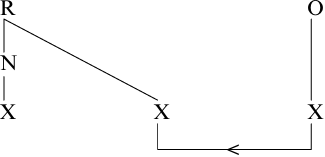

(2) at the interconstituent level, where e.g. an onset will govern a preceding rhymal complement; again we have strict locality and directionality, but here the direction is right to left:

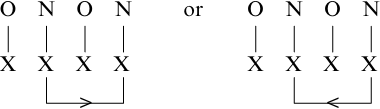

(3) at the level of nuclear projection, directionality is parametric:

Government is partly determined by whether segments are positively, negatively or neutrally `charmed' (although charm theory seems to play a less prominent part in more recent formulations of Government Phonology). The Projection Principle is adopted, ruling out underspecification, default rules and resyllabification. Finally, phonological processes all involve elemental composition or decomposition, seen as spreading or delinking of elements. Furthermore, such processes are local and non-arbitrary, in that there must be a clear connection between a process and its environment. Not only does there have to be a local source for a spreading element, for instance, but it also seems that some principle or parameter should generally be identifiable as providing motivation for the process in question to happen where it does. In Kaye's (1995: 301) words, `Events take place where they must.'

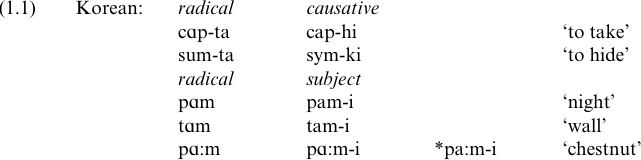

Our first sound change type is assimilation, which perhaps predictably involves elemental composition, with one locally present element spreading from its own segment onto another. Take, for instance, the case of Korean umlaut discussed in Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud (1990), and shown in (1.1).

Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud argue that the element I spreads from the suffix vowel in the causative or subject forms onto the stem vowel: fusion of the A and I elements will give the observed low front [a] vowel. The process cannot give equivalent results for the long vowel because the conditions for proper government (see Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud 1990) are not met with this configuration. This makes the interesting prediction that long vowels and heavy diphthongs should never in fact be affected by umlaut or harmony. There are, as Kaye, Low-enstamm and Vergnaud note, exceptions to this prediction, notably the case of umlaut in German. However, they say (1990: 226) that `the nature of German umlaut is still a subject of debate, in particular, as regards its current synchronic status. By contrast, Korean umlaut is totally productive.' While it might seem reasonable to rule out unproductive processes from consideration, German umlaut was at a certain historical period almost exceptionless, and it is unclear how Government Phonology could model that process, in the phonology of that period. To look at the problem from a rather different angle, it is not absolutely certain that we have resolved the problem of why Korean umlaut happens in the context where it does. Indubitably, we can model the process as the spread of the I element; and the I element is allowed to spread because it properly governs the nucleus on its left. But why, in fact, does it spread? Is it forced to spread because of the configuration in which it appears? If so, then we face clear difficulties in attempting to model any previous stage of Korean where the umlaut sound change had not yet operated: we would have to assume that at this earlier stage, the environment was different; or we predict that the earlier stage could not have existed at all. Conversely, if the spreading is not obligatory in this configuration, then the account is not really non arbitrary, and Kaye's (1995: 301) maxim that `Events take place where they must' is not adhered to.

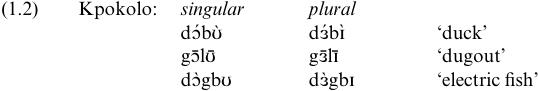

Similar difficulties arise with deletion. In Government Phonology, it is only possible to delete certain things, and only under certain circumstances. In general, the deletion of skeletal positions seems very highly constrained. One case, discussed in Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud (1985) and shown in (1.2), involves the vowel system of Kpokolo, an eastern Kru language spoken in the Ivory Coast.

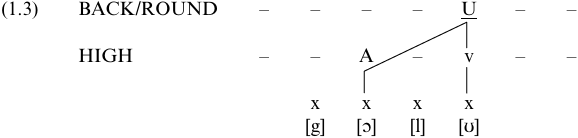

In the singular (see (1.3)), the rounding of the stem vowel, which is lexically represented as simply the element A, is taken to be a function of the suffix vowel, from which the rounding element, U, spreads.

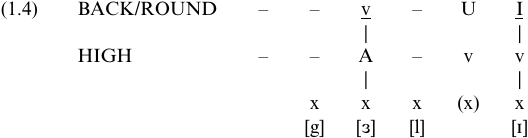

However, when the suffix vowel is added in the plural as shown in (1.4), the final rounded vowel is no longer permitted, since there cannot be two adjacent nuclei in a word, an effect Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud tentatively ascribe to the OCP. This means the bracketed position is deleted, leaving the U element floating. They argue that U cannot reassociate to either of the remaining vowels, since this element needs to be licensed by a rounded governor. Consequently the U element is not phonetically realized, and the stem vowel surfaces as unrounded.

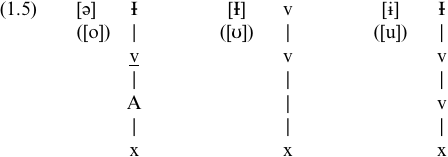

However, in other cases in Kpokolo, similar rounding alternations arise without any loss of a skeletal slot. Kpokolo has three back unrounded vowels, which alternate with the rounded vowels in brackets, as shown in example (1.5). The unrounding is accomplished by dis sociating the U element and replacing it with the cold vowel. The question is why the U is allowed to be dissociated here. It gives the right results; but it is presented simply as part of the description, without any reference to a principle which might control the dissociation. The conclusion at present must be that the deletion of segmental positions is better regulated than the deletion of single elements.

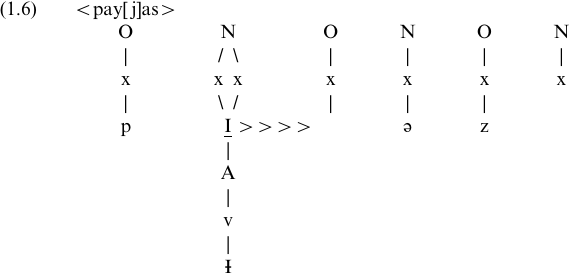

Apparent segmental insertion in Government Phonology typically involves spreading some locally present element, as in Broadbent's (1991) work on glide formation in West Yorkshire English, where [j] is found after high front vowels, and [w] after high back ones; this can be analyzed as the spread of the I or U element respectively (see (1.6)).

There are, however, some less clear cases of insertion of elements which do not have a local source, including Charette's (1990) account of vowel± zero alternations in French. In Moroccan Arabic, empty nuclei which are not properly governed surface as [ɨ], the independent realization of the cold vowel. However, in French, the alternation instead involves schwa, which has the A element as well as the cold vowel. Charette regards this as parametric variation, arguing that (1990: 235) `languages vary as to whether they choose the element A, I, U or simply nothing to add to the internal representation of the empty nucleus which contains as its only content the cold vowel'. This addition seems similar to the proposal in Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud (1990: 228) that `ambient elements', such as the positively charmed ATR element I Ɨ, might sometimes have to be added to an expression to satisfy the requirements of charm theory. Durand (1995: 287) accepts that `it is probably the case that a number of operations postulated by Government Phonology (e.g. ambient elements) should not be countenanced. Their arbitrariness is at least apparent whereas arbitrary insertions/deletions are the norm in the classical SPE framework.' However, if Government Phonologists have been proposing ambient elements, and must now choose not to countenance them, then the theory must sanction them, and is therefore not as constrained as it is claimed to be. In that case, there is rather little distance between this model and one like LP, where process types are unlimited but their application is limited by the constraints of the theory and the facts of the language itself. That is, an `arbitrary' deletion or insertion rule will simply reflect the fact that a particular segment is absent from or present in a particular context in a particular language. The only arbitrariness here results from history, which may render an earlier, transparent process opaque. In that case, searching for universal motivation in the Government Phonology sense is arguably misguided; indeed, if such motivation can always be found, this might in itself be the sign of an over-powerful theory, where spurious principles can be invented at will.

There is one further consequence of treating vowel-zero alternations as reflecting underlying empty nuclei. To quote Charette (1990: 252, fn. 17), `It ... follows from the Projection Principle that positions cannot be inserted. That is, new governing relations may not be created in the course of a derivation. Consequently, the theory denies vowel epenthesis as a phonological process.' Presumably this means that if a vowel which was not present on the surface at some earlier historical period becomes apparent at some later period, then we have to conclude that the empty nucleus was always there structurally, but not realized phonetically. So for instance, in cases like Latin schola to Spanish escuela or French e école, the empty nucleus is realized in the daughter languages but absent in the parent. The problem is working out the conditions for this: why should the empty nucleus be properly governed in the first case but not in the second, when in all cases there is a full vowel in the next syllable?

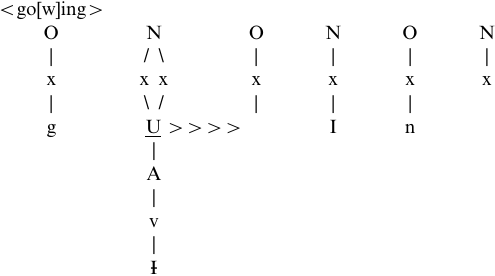

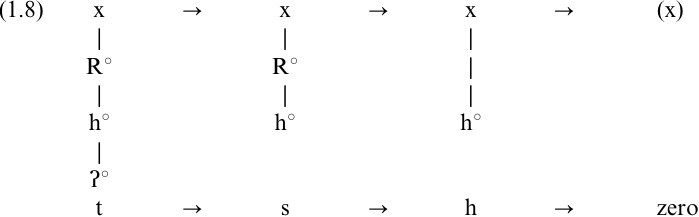

Lenition in Government Phonology involves elemental decomposition, or reduction in segmental complexity. To take one fairly straightforward example (1.7), the case of Korean /p/ → [w] and /t/ → [r] can be seen as the delinking of the occlusion element.

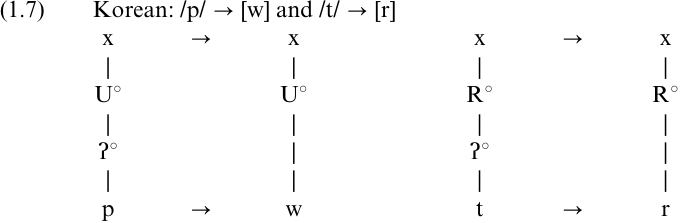

It is also possible (Harris 1990) to regard trajectories of lenition as the progressive decomposition of elements; (1.8) shows a typical sequence from /t/ to /s/ to /h/ to zero.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Government work on lenition is Harris's (1992) work on prime lenition sites, which informally are word-final, preconsonantal and intervocalic: these are unified by inheriting their a-licensing potential, which determines the segmental material they can tolerate, from a position which is itself licensed; thus, such positions can support a smaller range of less complex segments. The difficulty here lies perhaps in deciding which elements to delink in a particular prime lenition site, and indeed how many. Is there a parameter for the reduction process? And if so, how was it reset? If the parameter can only be reset on the basis of what people are already doing, this is not really explanatory, and we may still need an external, perhaps phonetic, account of why the change happened in the first place.

Similar problems arise with respect to other deletion changes, such as Brockhaus's (1990) account of German final devoicing, which she characterizes as loss of the L element (slack vocal cords, or voicing in a complex segment) after a branching nucleus or rhyme, and before an empty nucleus. In some dialects, only final empty nuclei trigger the process, and Brockhaus claims that this is defined parametrically. Again, however, we encounter a difficulty when we see final devoicing in historical perspective, since we know from written records that at an earlier stage of German, final devoicing did not operate, at least phonologically. Before devoicing, were there then no empty nuclei? If there were, why did they not cause final devoicing? Furthermore, to what extent is the association of process and context here really non-arbitrary; in other words, why is it the L element that disappears? Of course, L must delink to produce the right results on voicing, but this is purely descriptive, not explanatory. It is quite true, as Brockhaus points out, that final devoicing takes place in the context of an empty nucleus, and that it is always L that is delinked, but this does not tell us what property of the empty nucleus makes L in particular go away.

Finally, there is little in the Government Phonology literature about fortition. Harris (1990) points out that, logically, if lenition is elemental decomposition, then fortition should be composition, and analyses the Sesotho case shown in (1.9) as spreading of the occlusion element.

(1.9) Sesotho: /f/ → /p/, /r/ → /t/ after nasals

=spreading of occlusion elementʔ° from nasal.

However, this analysis is entirely counter-historical: Bantuists seem to agree that the sound change involved was in fact a straightforward lenition except in the protected environment following a nasal (Bruce Connell personal communication, Guthrie 1967-71, Janson 1991-2). Worse still, Foulkes (1993), in a rigorous cross-linguistic survey of /p/ > /f/ (> /h/) changes, fails to find a single case of the reverse shift. It must be a matter of concern that Government Phonology, as a theory intended to be restrictive in the sense of only dealing with attested process types, can with such facility model a change which in all probability did not, and perhaps could not, happen.

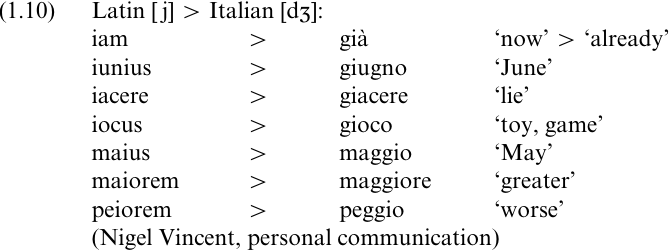

Furthermore, Harris notes that he cannot model what he calls `spontaneous' fortition, notably Latin maior → Italian maggiore. Again, this might reflect spread of the occlusion element, but this time there is no immediate source. Harris suggests that this is perhaps not of great concern, as the change is so sporadic: but there are numerous cases where the same [j] to [dƷ] change happens between Latin and Italian, as shown in (1.10). Indeed, there seem to be no cases with the same conditions where the supposedly sporadic fortition fails; so this may in fact be a real problem for Government Phonology, especially as such fortitions are repeated elsewhere in Romance (for instance in River Plate Spanish, where [j] from <-ll>, Castilian [ʎ], has regularly become [Ʒ], or initial [dƷ] alternating with medial [Ʒ]).

Some rather similar problems arise in OT, although very few cases of sound change are discussed in the OT literature to date, and I therefore limit my comments here to cases of apparent insertion and deletion. As we have seen, OT involves the generation of candidate parses from a lexical entry; these are then evaluated by a language specifically ranked set of universal constraints, and the maximally harmonic parse, which violates the fewest high-ranking constraints, is selected. This evaluation process can be represented in the type of constraint tableau shown in (1.11) for the two constraints ONS and HNUC and Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber, where any segment can be a syllable nucleus. Given a sequence /ul/, either the first segment will be parsed as nuclear, or the second. The harmonic parse is the latter, with the lateral nuclear. Therefore we assume that ONS must dominate HNUC in Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber. In constraint tableaux, * signals a `black mark' assigned by a violated constraint, while ! indicates that the violation is fatal to that parse.

(1.11) ONS: syllables must have an onset

HNUC:Nuclear Harmony Constraint. Higher sonority nuclei are more harmonic.

Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber: possible syllabifications of /ul/:

Candidates ONS HNUC

☞ .wL. |I|

.Ul *! |u|

Constraint interaction also accounts for phonological behavior which has generally been analyzed by means of processes. In cases of apparent insertion or deletion, the constraints involved are crucially FILL and PARSE, outlined in (1.12). If these faithfulness constraints are globally respected, then clearly FILL will ban insertion, and PARSE will ban deletion; but they may be violated because of higher-ranking constraints.

(1.12) FILL: outputs must be based on inputs, i.e. empty nodes are banned. All nodes must be properly filled.

PARSE: all underlying material must be analyzed, or attached to a node. Unparsed material (i.e. unfilled nodes, and underlying lexical material not attached to nodes) is phonetically unrealized. (This has equivalent effects to Stray Erasure in other frameworks.)

In more recent versions of OT (see Roca (ed.) 1997a), FILL and PARSE are replaced by the correspondence constraints DEP-IO and MAX-IO (whereby every element of the input is an element of the output, and vice versa); however, their effects seem sufficiently similar to allow illustration using FILL and PARSE.

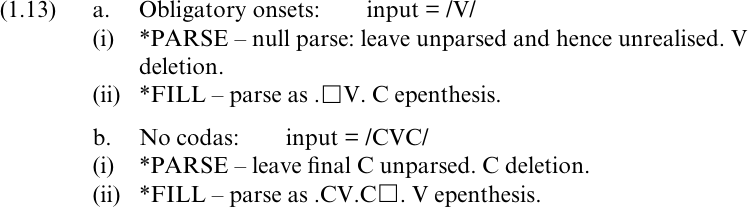

Let us first take two schematic cases: language (1.13a) requires onsets, and (1.13b) forbids codas. In (1.13a), for an input structure consisting of a single V, syllabification gives two options. We can violate PARSE by simply not parsing this vowel; that means the vowel cannot be realized phonetically, so this option results effectively in vowel deletion (although we are really leaving the structure floating or unattached, rather than deleting it sensu stricto). Alternatively, we can violate FILL by creating an empty onset slot, giving consonant epenthesis. Turning to (1.13b), an input string of /CVC/ cannot be syllabified without violating the prohibition on codas, unless we again violate PARSE or FILL. This time, violating PARSE gives effective consonant deletion by leaving the final C unparsed, while violating FILL creates an empty nuclear slot and hence a second syllable; feature fill-in of some sort instantiates a vowel, giving a percept of vowel epenthesis.

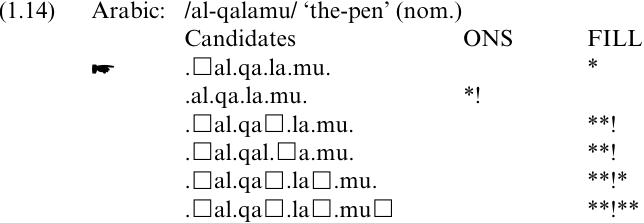

A real-language example from Arabic, where onsets are obligatory, is shown in (1.14). If there is no onset, a glottal stop is supplied, and this is a violation of FILL. We conclude that ONS dominates FILL.

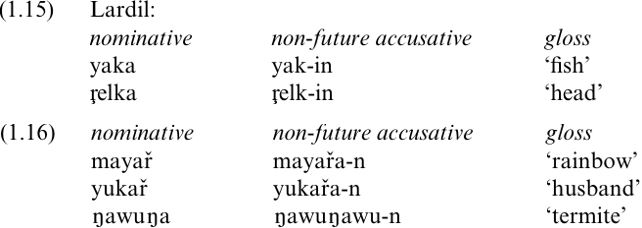

A second case is from Lardil, where short noun stems are augmented and long ones truncated in the nominative. Augmentation (see (1.15)) involves a further violation of FILL: the optimal parse supplies an empty nuclear slot, and phonetic material is supplied. Truncation is slightly more difficult; relevant data appear in (1.16). Here, PARSE is violated ± the final vowel is left unparsed and therefore unrealizable, and because of restrictions on the coda in Lardil, preceding consonants are typically also lost, as in the `termite' example. PARSE is violated here due to the higher-ranking (and language-specific) constraint, FREE-V, shown in (1.17).

(1.17) FREE-V:

Word-final vowels must not be parsed (in the nominative).' (Prince and Smolensky 1993: 101)

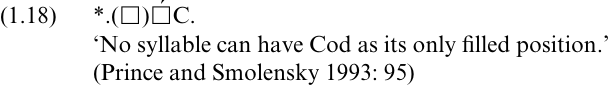

The OT account of insertion and deletion is problematic in several respects. First, there is an issue of restrictiveness. Prince and Smolensky argue that epenthesis can take place only in an onset where the nucleus is filled, or in a nucleus where the onset is filled, so ruling out (1.18).

However, epentheses of this kind do seem to occur, as in the well known Romance schola > école cases. Prince and Smolensky admit this, and say `we must argue ... that other constraints are involved' (1993: 96), but give no indication of what other constraints. We also face the problem of supplying the right phonetic material in epenthetic positions. If overparsed nodes are `phonetically realized through some process of filling in default featural values' (1993: 88), it follows that the glottal stop should be the default, or maximally underspecified, or unmarked Arabic consonant. Similarly, we assume from the Lardil data that the default Lardil vowel is /a/. For French initial vowel epenthesis, like e école, étoile, presumably the same conclusion follows for /e/, although (Durand 1990) typically several French vowels are analyzed as more underspecified than /e/, including /i/, /a/, /u/ and schwa. Similarly with PARSE violation, underlying segments may be unrealized, or underlying long vowels shortened because moras are unparsed, but this may have phonetic consequences, for instance on vowel quality, and it is not clear how we are to account for these.

Assuming we can produce the correct parse, and provide (or dispose of) the appropriate phonetic material, there is still the issue of why the old form was harmonic then, and the new one is now. If change reflects constraint re-ordering, we are faced with much the same options and problems as the principles and parameters approach of Government Phonology, since there are the same questions of how re-ranking occurs, and what motivates it. Finally, as we have already seen, issues around the type, number, ordering and variant cases of constraints are still to be addressed.

In returning now to a rule-based model, I do not pretend to have answered all the questions which might be raised by proponents of alternative phonologies. This topic is also in a sense incomplete, since I have not shown how LP can model the types of sound change surveyed above. To some extent, this is a non-issue: we might say that it can model anything, which is at the heart of the problem for any model with parochial rules. I hope to show below that these unwelcome abilities can be limited for LP. Secondly, whether such changes can be modelled sensibly depends in large part on the feature system; there are long-standing difficulties with the binary features generally associated with the SPE model, and hence with LP, and I return to these below. Needless to say, if the model of LP I propose here turns out to perform badly, in the analysis of synchronic alternations and in the other domains discussed above, it cannot reasonably be maintained on the grounds that no-one else is doing any better. On the other hand, I hope I have raised enough questions to justify at least considering the performance of a radically revised generative model. Once the investigation is under way, the results will speak for themselves.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)