Energy levels

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 38

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 38

2024-04-30

2024-04-30

1883

1883

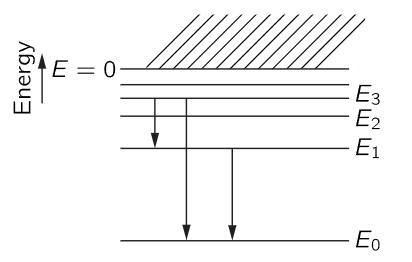

We have talked about the atom in its lowest possible energy condition, but it turns out that the electron can do other things. It can jiggle and wiggle in a more energetic manner, and so there are many different possible motions for the atom. According to quantum mechanics, in a stationary condition there can only be definite energies for an atom. We make a diagram (Fig. 38–9) in which we plot the energy vertically, and we make a horizontal line for each allowed value of the energy. When the electron is free, i.e., when its energy is positive, it can have any energy; it can be moving at any speed. But bound energies are not arbitrary. The atom must have one or another out of a set of allowed values, such as those in Fig. 38–9.

Fig. 38–9. Energy diagram for an atom, showing several possible transitions.

Now let us call the allowed values of the energy E0, E1, E2, E3. If an atom is initially in one of these “excited states,” E1, E2, etc., it does not remain in that state forever. Sooner or later, it drops to a lower state and radiates energy in the form of light. The frequency of the light that is emitted is determined by conservation of energy plus the quantum-mechanical understanding that the frequency of the light is related to the energy of the light by (38.1). Therefore, the frequency of the light which is liberated in a transition from energy E3 to energy E1 (for example) is

This, then, is a characteristic frequency of the atom and defines a spectral emission line. Another possible transition would be from E3 to E0. That would have a different frequency

Another possibility is that if the atom were excited to the state E1 it could drop to the ground state E0, emitting a photon of frequency

The reason we bring up three transitions is to point out an interesting relationship. It is easy to see from (38.14), (38.15), and (38.16) that

In general, if we find two spectral lines, we shall expect to find another line at the sum of the frequencies (or the difference in the frequencies), and that all the lines can be understood by finding a series of levels such that every line corresponds to the difference in energy of some pair of levels. This remarkable coincidence in spectral frequencies was noted before quantum mechanics was discovered, and it is called the Ritz combination principle. This is again a mystery from the point of view of classical mechanics. Let us not belabor the point that classical mechanics is a failure in the atomic domain; we seem to have demonstrated that pretty well.

We have already talked about quantum mechanics as being represented by amplitudes which behave like waves, with certain frequencies and wave numbers. Let us observe how it comes about from the point of view of amplitudes that the atom has definite energy states. This is something we cannot understand from what has been said so far, but we are all familiar with the fact that confined waves have definite frequencies. For instance, if sound is confined to an organ pipe, or anything like that, then there is more than one way that the sound can vibrate, but for each such way there is a definite frequency. Thus, an object in which the waves are confined has certain resonance frequencies. It is therefore a property of waves in a confined space that they exist only at definite frequencies. And since the general relation exists between frequencies of the amplitude and energy, we are not surprised to find definite energies associated with electrons bound in atoms.

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الذرية

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الذرية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة