Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Influence of other languages

المؤلف:

Kent Sakoda and Jeff Siegel

المصدر:

A Handbook Of Varieties Of English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

732-41

2024-04-29

1707

Influence of other languages

We have already mentioned that many words from Hawaiian came into Hawai‘i Creole through Pidgin Hawaiian and Pidgin English. But the structure of Hawaiian has also affected the structure of Hawai‘i Creole, making it different from that of English. One example is word order. In Hawaiian, there are sentences such as Nui ka hale. Literally this is ‘Big the house’, which in English would be ‘The house is big’. Similarly, in Hawai‘i Creole we find sentences such as Big, da house and Cute, da baby.

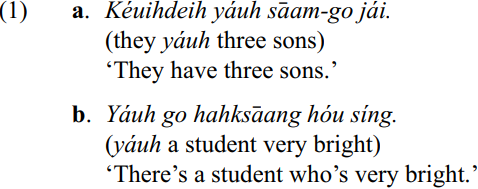

Other languages also appear to have influenced the structure of Hawai‘i Creole more than the vocabulary. One such language is Cantonese. For example, in Cantonese one word yáuh is used for both possessive and existential sentences, i.e. meaning both ‘have/has’ and ‘there is/are’, as in these examples below (from Matthews and Yip 1994):

Similarly, in Hawai‘i Creole one word get is used for both possessive and existential, as in (2):

Portuguese appears to have affected the structure of Hawai‘i Creole even more. For instance, Portuguese uses the word para meaning ‘for’ to introduce infinitival clauses, where Standard English uses to, as in (3):

Similarly, for (or fo) is used in Hawai‘i Creole:

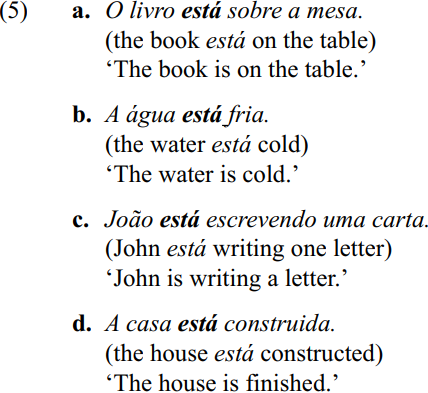

The Portuguese copula/auxiliary estar (with various conjugations such as está) has several different functions, including copula with locations and adjectives, auxiliary for present progressive, and marker for perfective, as in the examples in (5):

In Hawai‘i Creole, the word stay has the same functions:

The phonology of Hawai‘i Creole also has some similarities to that of Hawaiian, Cantonese and Portuguese, especially in the vowel system and intonation in questions, but these connections have not been studied in any detail.

Thus, the ethnic groups whose languages most influenced the structure of Hawai‘i Creole seem to have been the Hawaiians, Chinese and Portuguese. But the influence of the Hawaiians declined steadily as their numbers declined and the numbers of other ethnic groups increased. By 1900, there were more Portuguese and Chinese than Hawaiians and Part-Hawaiians. Even though the Japanese were by far the largest immigrant group, their language seems to have had little effect on the structure of Hawai‘i Creole. One reason for this was first pointed out by the famous Hawai‘i Creole scholar, John Reinecke, who wrote (1969: 93): “The first large immigration of Japanese did not occur until 1888 when the Hawaiian, Chinese and Portuguese between them had pretty well fixed the form of the ‘pidgin’ [English] spoken on the plantations.”

Another reason is that, as we have seen, it was the locally born members of immigrant groups who first used Pidgin English as their primary language and whose mother tongues influenced the structure of the language. This structure was then passed on to their children in the development of Hawai‘i Creole. When the creole first began to emerge, the locally born population was dominated by the Chinese and Portuguese. Of these two groups, the Portuguese were the more important. In 1896, they made up over half of the locally born immigrant population. For the Portuguese, the number of locally born came to equal the number of foreign born in 1900, whereas this did not happen for the Chinese until just before 1920 and for the Japanese not until later in the 1920s.

The Portuguese were also the most significant immigrant group in the schools. They were the first group to bring their families, and their demands for education for their children in English rather than Hawaiian were partially responsible for the increase in English-medium public schools. From the critical years of 1881 until 1905, Portuguese children were the largest immigrant group in the schools, with over 20 percent from 1890 to 1905.

Another factor was that the Portuguese, being white, were given a disproportionate number of influential positions on the plantations as skilled laborers, clerks and lunas ‘foremen’ who gave orders to other laborers. In fact, the number of Portuguese lunas was three times larger than that of any other group.

The Portuguese community was also the first to shift from their traditional language to Hawai‘i Creole. By the late 1920s, the Portuguese had the lowest level of traditional language maintenance, and the greatest dominance of English or Hawai‘i Creole in the homes, followed by the Hawaiians and then the Chinese.

But that is not to say that Japanese has had no influence on Hawai‘i Creole. Many Japanese words have come into the language, and several Hawai‘i Creole expressions, such as chicken skin ‘goose bumps’, are direct translations of Japanese. Also, the way many discourse particles are used, such as yeah and no at the end of a sentence, seems to be due to Japanese influence. Furthermore, the structure of narratives in Hawai‘i Creole is very similar to that of Japanese.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)