Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

how vastly languages diverge from one another over time

المؤلف:

P. John McWhorter

المصدر:

The Story of Human Language

الجزء والصفحة:

38-8

2024-01-10

1095

Although the Indo-European languages have a great deal in common, they also demonstrate how vastly languages diverge from one another over time.

A. Germanic.

1. This group includes German, Dutch, Swedish and its close relatives Norwegian and Danish, Icelandic, Yiddish, and a few lesser-known languages, such as Frisian and Faroese, as well as Afrikaans spoken in South Africa.

2. A strange sound change took place in the ancestor of this group, explained by Grimm’s law, which was named after its discoverer, the same Jacob Grimm who collected folk tales.

Grimm’s Law: Latin and Greek to English

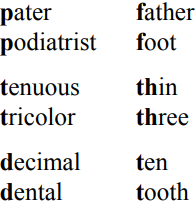

For some reason, in many places where Proto-Indo-European had a p, Proto-Germanic switched this to an f. This is why Latin has pater and Sanskrit has pitár, but English has father and German has Vater (pronounced “FAH-ter”). There were many switches like this; t changed to a th sound in Germanic, so that while a word we borrowed from Latin, such as tenuous, has a t, the native Germanic rendition of the word has a th. In the same way, Proto-Indo-European’s d changed into a t in Germanic. This is why we have ten where Latin had decem, the root in some words we borrowed, including decimal, and why we have tooth where Latin had dēns, Sanskrit had dán, and Ancient Greek had odón.

B. Celtic.

1. These languages are now few, all under severe threat: Irish Gaelic, Scotch Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton spoken in France. Celtic was once spoken across Europe and even in what is now Turkey, but the languages have been edged to the western fringe of Europe by waves of invaders.

2. Celtic languages are well known for their mutations, where proper expression requires switching consonants at the beginning of words for no apparent reason, and sometimes the switch alone conveys important meanings.

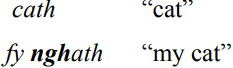

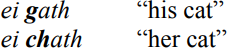

In Welsh, the word for cat is cath, but to say my cat requires also changing the initial c to ngh. And then, this kind of change is the only way to distinguish between his cat and her cat.

C. Baltic versus Italic: Old-fashioned versus up-to-the-minute.

1. Some languages are more conservative than others–that is, they change more slowly. Some Indo-European families have retained a striking amount of Proto-Indo-European structure over the millennia. Others have shed a surprising amount. Lithuanian is of the Baltic family (which today has only one other member, Latvian), and it preserves seven cases, a record among living Indo-European members.

2. As it happens, one of the Indo-European groups most familiar to us is one of the least “faithful” to its ancestor in terms of case endings. Italic once included Latin and other dead languages, but today lives only through the children of Latin alone; Spanish is one. Spanish has not a single one of the Proto-Indo-European case endings. (There is a likely reason for this kind of difference, which we will explore later.)

D. Albanian and Armenian: Black sheep.

1. Other groups have been so innovative that they are difficult to even recognize as family members. Albanian is the language that would have been spoken by the Twelfth Night characters because the play takes place east of the Adriatic in the Illyrian region. Armenian is spoken between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. Both of these languages are the only members of their family.

2. Both have borrowed many words from other language groups: only about 1 in 12 Albanian words is native to the language and only about 1 in 4 Armenian ones. Both languages have also wended quite far along their own paths of development. Albanian wasn’t even discovered to be Indo-European until 1854, and Armenian was long thought to be a kind of Persian. Here are the numbers 2 through 9 in Albanian and Armenian, compared to “normal” Indo-European languages. The Albanian and Armenian words come from the same ancestor as the other languages’ words do, but look how differently they often come out:

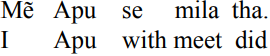

E. Indo-European: The “Indo” part. In India, Indo-European languages have taken on many features from the grammars of languages spoken by peoples who first occupied the area, such as the Dravidian languages that are still spoken in southern India today, including Tamil. An example is word order. In Hindi, the verb comes at the end of the sentence, and prepositions come after nouns. Thus, in Hindi, I met Apu is “I Apu-with met-did.”

“I met Apu.”

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)