The minimal pair test

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

86-5

الجزء والصفحة:

86-5

2023-12-14

2023-12-14

1821

1821

The minimal pair test

The distinctive speech units of a language are called phonemes: phonemes may have several realizations, or allophones. Phonemes and allophones can be determined by the minimal pair test: if commuting two sounds in a word results in a change of meaning, then the sounds are in phonemic opposition; if they do not, the sounds are allophones of the same phoneme.

Secondly, in those varieties that use both allophones it is possible to predict the range of environments or distribution of each. Clear l [l] occurs prevocalically at the start of a syllable, while dark l [ɫ] occurs in postvocalic positions. Because the two sounds cannot occur in the same environment for these speakers, they cannot contrast words. As more than one linguist has put it, they are a bit like Superman and Clark Kent: never seen together in the same place, because each is one part of the same whole. This is known as complementary distribution.

To take another example, try saying copy and kitchen, paying particular attention to the two initial consonants. For most English speakers, it’s highly likely that your tongue will leap forward for the second word, and although they sound similar, it should be evident that the two consonants are in fact distinct: the first is a velar plosive, pronounced at the soft palate at the rear of the vocal tract, while for the latter the sound is produced further forward, at the hard palate behind the alveolar ridge, the sounds are therefore voiceless velar and palatal plosives respectively, with the IPA symbols [k] and [c] (the wrong way round from the point of view of the spelling!): their voiced equivalents, heard in got and give respectively, have the symbols [g] and  . The distribution is therefore phonetically conditioned, in that the fronted consonants [c] and

. The distribution is therefore phonetically conditioned, in that the fronted consonants [c] and  occur before front vowels such as [i] while [k] and [g] occur before back vowels such as

occur before front vowels such as [i] while [k] and [g] occur before back vowels such as  .

.

One can see how this might make life easier for the English speaker: by advancing the tongue in readiness for a front vowel and retracting it for a back one, a little articulatory effort is saved. But not all languages work in the same way: in Hungarian, for example, the palatal/velar contrast is phonemic, rather than allophonic as in English. To determine whether two sounds are phonemes, phonologists apply the minimal pair test: can we identify two different words that differ only by virtue of one sound? On this test, /k/ and /t/ are phonemes of English on the strength of kick/tick, pick/pit, school/stool and many other pairs. Clear and dark l on the other hand have no pairs in which they contrast, because they never occur in the same environments (and, as we saw, if we force the issue by switching them in their respective environments, we do not get a change in meaning), so these sounds are both allophones of  .

.

For a final example of complementary distribution, you’ll need a single sheet of paper. Hold it about 3–4 cm in front of your mouth and say pip several times, and then bib; now do the same thing with kick and gig. You will notice that the paper moves considerably for pip and kick but less so for bib and gig, and (since the vowel is unchanged) you might suspect that this has something to do with the consonants involved. What matters here is whether the first consonant is a voiceless plosive like /p/ or /k/: these are pronounced with greater articulatory force than their voiced counterparts – hence the alternative terms fortis and lenis (‘strong’ and ‘weak’) for voiceless and voiced consonants respectively – and at the start of stressed syllables are accompanied by a small outbreath or aspiration, represented in narrow transcription by a superscript [h].

Now try the paper experiment again, this time with pin and spin: this time the paper moves in the former but not the latter case. This is because aspiration of /p/, /t/ and /k/ does not happen after /s/, so pin is realized [phIn] but spin is [spIn]. Again, it is an arbitrary fact about English that aspiration is non-phonemic, i.e. cannot be used to distinguish words, as it can in Thai:

[paa] ‘forest

[phaa] ‘to pound’

[tam] ‘to split’

[tham] ‘to do’

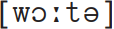

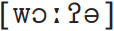

In some cases, the differences between allophones of a given phoneme may be quite wide. The distance in articulatory terms, for example, between the closure of the glottis required for a glottal stop [?] and the closure formed between tongue and teeth or alveolar ridge for [t] could hardly be greater, but Cockney, Glaswegian and many other English speakers perceive them as being ‘the same sound’ in that one may say water as  or

or  and mean the same thing.

and mean the same thing.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة