Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Autosegmental contours

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

288-8

12-4-2022

1599

Autosegmental contours

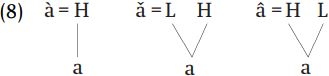

A resolution of this problem was set forth in Goldsmith 1976, who proposed that tones be given an autonomous representation from the rest of the segment, so that regular segments would be represented at one level and tones would be at another level, with the two levels of representation being synchronized via association lines. This theory, known as autosegmental phonology, posited representations such as those in (8).

The representation of [á] simply says that when the rest of the vocal tract is in the configuration for the vowel [a], the vocal folds should be vibrating at a high rate as befits an H tone. The representation for [a˘] on the other hand says that while the rest of the vocal tract is producing the short vowel [a], the larynx should start vibrating slowly (produce an L tone), and then change to a higher rate of vibration to match that specified for an H tone – this produces the smooth increase in pitch which we hear as a rising tone. The representation of [â] simply reverses the order of the tonal specifications.

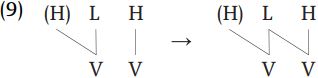

The view which autosegmental phonology takes of rules is different from that taken in the classical segmental theory. Rather than viewing the processes in (2) as being random changes in feature values, autosegmental theory views these operations as being adjustments in the temporal relations between the segmental tier and the tonal tier. Thus the change in (2a) where H becomes rising after L and fall can be expressed as (9).

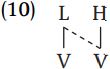

By simply adding an association between the L tone element on the left and the vowel which stands to the right, we are able to express this tonal change, without changing the intrinsic feature content of the string: we change only the timing relation between tones and vowels. This is notated as in (10), where the dashed association line means “insert an association line.”

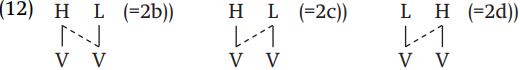

Two other notational conventions are needed to understand the formulation of autosegmental rules. First, the deletion of an association line is indicated by crossing out the line:

Second, an element (tone or vowel) which has no corresponding association on the other tier (vowel or tone) is indicated with the mark [ˊ], thus Vˊ indicates a toneless vowel and Hˊ indicates an H not linked to a vowel.

One striking advantage of the autosegmental model is that it allows us to express this common tonal process in a very simple way. The theory also allows each of the remaining processes in (2) to be expressed equally simply – in fact, essentially identically as involving an expansion of the temporal domain of a tone either to the left or to the right.

The problem of the natural classes formed by contour tones and level tones was particularly vexing for the linear theory. Most striking was the fact that what constitutes a natural class for contour tones depends on the linear order of the target and conditioning tones. If the conditioning tones stand on the left, then the natural classes observed are {L,F} and {H,R}, and if the conditioning tones stand on the right, then the natural groupings are {L,R} and {H,F}. In all other cases, the groupings of elements into natural classes are independent of whether the target is to the right or the left of the trigger. The autosegmental representation of contour tones thus provides a very natural explanation of what is otherwise a quite bizarre quirk in the concept “natural class.”

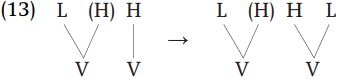

The autosegmental model also provides a principled explanation for the nonexistence of rules such as (4), i.e. the rules H ! F / {L,R} _ and L ! R / {H,F} _. The change of H to F after L would involve not just an adjustment in the temporal organization of an L-H sequence, but would necessitate the insertion of a separate L to the right of the H tone, which would have no connection with the preceding L; the change of H to F after R is even worse in that the change involves insertion of L when H is remotely preceded by a L. Thus, the closest that one could come to formalizing such a rule in the autosegmental approach would be as in (13).

As we will discuss, autosegmental theory resulted in a considerable reconceptualization of phonological processes, and the idea that rules should be stated as insertions and deletions of association relationships made it impossible to express certain kinds of arbitrary actions, such as that of (13).

In addition to the fact that the theory provides a much-needed account of contour tones, quite a number of other arguments can be given for the autosegmental theory of tone. The essential claim of the theory is that there is not a one-to-one relation between the number of tones in an utterance and the number of vowels: a single tone can be associated with multiple vowels, or a single vowel can have multiple tones. Moreover, an operation on one tier, such as the deletion of a vowel, does not entail a corresponding deletion on the other tier. We will look at a number of arguments for the autonomy of tones and the vowels which phonetically bear them.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)