Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Abstract reanalysis in Matuumbi NC sequences

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

271-8

12-4-2022

1515

Abstract reanalysis in Matuumbi NC sequences

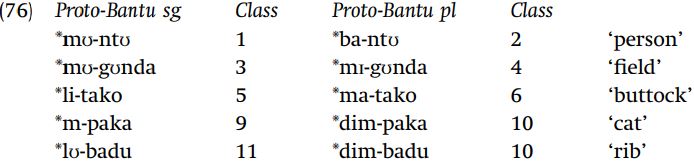

Other evidence for abstract phonology comes from a historical reanalysis of postnasal consonants in the Bantu language Matuumbi. Nouns in Bantu are composed of a prefix plus stem, and the prefix changes between singular and plural. For example, proto-Bantu mu-ntu ‘person’ contains the class 1 prefix mu- marking certain singular nouns, and the plural ba-ntu ‘people’ contains the class 2 prefix ba-. Different nouns take different noun-class prefixes (following the tradition of historical linguistics, reconstructed forms are marked with an asterisk).

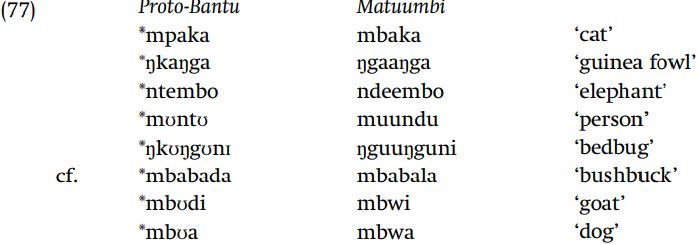

A postnasal voicing rule was added in the proto-Rufiji-Ruvuma subgroup of Bantu (a subgroup which includes Matuumbi), so that original *mpaka ‘cat’ came to be pronounced mbaka in this subgroup.

Another inconsequential change is that the class 10 prefix, originally *din-, lost di, so the class 10 prefix became completely homophonous with the class 9 prefix.

In the Nkongo dialect of Matuumbi, there was a change in the morphological system so that nouns which were originally assigned to classes 9–10 now form their plurals in class 6, with the prefix ma-. Earlier *ŋaambo ‘snake ~ snakes’ now has the forms ŋáambo ‘snake’ / ma-ŋáambo ‘snakes.’

Given surface [mbwa] ‘dog’ (proto-Bantu *m-bʊa) originally in classes 9– 10, the concrete analysis is that the underlying form in proto-Rufiji is /m-bwa/. It was always pronounced as [mbwa], since the root was always preceded by a nasal prefix. The absence of alternations in the phonetic realization of the initial consonant would give reason to think that phonetic [b] derives from underlying /b/. By the same reasoning, we predict that earlier mpaka ‘cat’ is reanalyzed as /b/, once the word came to be pronounced as mbaka in all contexts: compare Yiddish gelt.

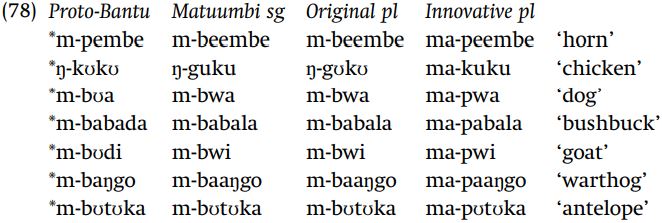

The restructuring of the morphological system of Nkongo Matuumbi where the original class pairing 9–10 is reanalyzed as 9–6 allows us to test this prediction, since nouns with their singulars in class 9 no longer have a nasal final prefix in all forms; the plural has the prefix ma-. As the following data show, the concrete approach is wrong.

While the distinction /mp/ ~ /mb/ was neutralized, it was neutralized in favor of a phonetically more abstract consonant /p/ rather than the concrete consonant /b/.

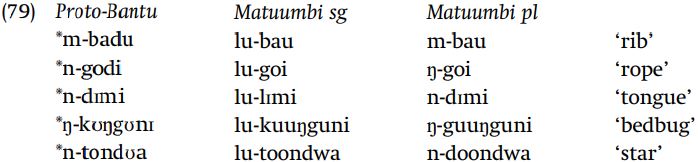

This reanalysis did not affect all nouns which had a singular or plural in classes 9–10; it affected only nouns which originally had both their singulars and plurals in this class, i.e. only those nouns lacking alternation. Nouns with a singular in class 11 and a plural in class 10 preserve the original voicing of the consonant.

A word such as ‘rib’ always had a morphological variant which transparently revealed the underlying consonant, so the contrast between /n-toondwa/ ! [ndoondwa] and /n-goi/ ! [ŋgoi] was made obvious by the singulars [lu-toondwa] and [lu-goi].

While it is totally expected that there should be a neutralization of *mp and *mb in words like mbaka, mbwa – there would have been no evidence to support a distinction between surface [mb] deriving from /mb/ versus [mb] deriving from /mp/ – surprisingly from the viewpoint of concrete phonology, the direction of neutralization where [mb] is reanalyzed as /mp/ is unexpected. One explanation for this surprising reanalysis regards the question of markedness of different consonants. Given a choice between underlying /m + b/ and /m + p/, where either choice would independently result in [mb], one can make a phonetically conservative choice and assume /m + b/, or make a choice which selects a less marked consonant, i.e. /m + p/. In this case, it is evident that the less marked choice is selected where the choice of consonants is empirically arbitrary.

Such examples illustrating phonetically concrete versus abstract reanalyses motivated by considerations such as markedness are not well enough studied that we can explain why language change works one way in some cases, and another way in other cases. In the case of Yiddish avek from historically prior aveg, there would be no advantage at all in assuming underlying /aveg/, from the perspective of markedness or phonetic conservatism.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)