Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Rule formulation and features

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

65-3

25-3-2022

1419

Rule formulation and features

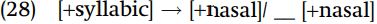

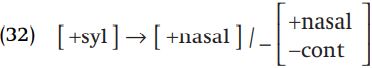

The most important function of features is to form the basis for writing rules, which is crucial in understanding what defines a possible phonological rule. A typical rule of vowel nasalization, which nasalizes all vowels before a nasal, can be formulated very simply if stated in features:

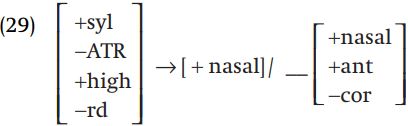

Such a rule is common in the languages of the world. Very uncommon, if it exists at all, is one nasalizing only the lax vowel [ɪ], and only before [m]. Formulated with features, that rule looks as follows:

This rule requires significantly more features than (28), since [ɪ], which undergoes the rule, must be distinguished in features from other high vowels, such as [i] or [ʊ], which (in this hypothetical case) do not undergo the rule, and [m], which triggers the rule, must be distinguished from [n] or [ŋ], which do not.

Simplicity in rule writing. This relation between generality and simplicity on the one hand, and desirability or commonness on the other, has played a very important role in phonology: all things being equal, simpler rules are preferred, both for the intrinsic elegance of simple rules and because they correlate with more general classes of segments. Maximum generality is an essential desideratum of science.

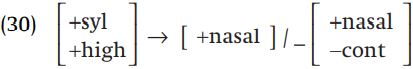

The idea that rules are stated in terms of the simplest, most general classes of phonetically defined segments has an implication for rule formulation. Suppose we encounter a rule where high vowels (but not mid and low vowels) nasalize before nasal stops (n, m, ŋ), thus in ! ĩn, uŋ ! ũŋ, and so on. We would formulate such a rule as follows:

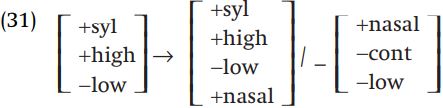

However, we could equally well formalize the rule as:

We could freely add [-low] to the specification of the input segment (since no vowel can be [+high, +low] , thus high vowels automatically would pass that condition), and since the same class of vowels is referenced, inclusion of [-low] is empirically harmless. Saying that the vowel becomes [+syl, +high, -low] is harmless, since the vowel that undergoes the change already has these specifications. At the same time, the additional features in (31) are useless complications, so on the theoretical grounds of simplicity, we formalize the rule as (30). In writing phonological rules, we specify only features which are mandatory. A formulation like would mention fewer features, but it would be wrong given the facts which the rule is supposed to account for, since the rule should state that only high vowels nasalize, but this rule nasalizes all vowels.

Likewise, we could complicate the rule by adding the retriction that only non-nasal vowels are subject to (30): in (30), we allow the rule to vacuously apply to high vowels that are already nasal. There is (and could be) no direct evidence which tells us whether /ĩn/ undergoes (30) and surfaces as [ĩn], or /ĩn/ is immune to (30) and surfaces as [ĩn]; and there is no conceptual advantage to complicating the rule to prevent it from applying in a context where we do not have definitive proof that the rule applies. The standard approach to rule formalization is, therefore, to write the rule in the simplest possible way, consistent with the facts.

Formalizability. The claim that rules are stated in terms of phonetically defined classes is essentially an axiom of phonological theory. What are the consequences of such a restriction? Suppose you encounter a language with a phonological rule of the type {p, r} ! {i, b}/ _ {o, n}. Since the segments being changed (p and r) or conditioning the change (o and n) cannot be defined in terms of any combination of features, nor can the changes be expressed via any features, the foundation of phonological theory would be seriously disrupted. Such a rule would refute a fundamental claim of the theory that processes must be describable in terms of these (or similar) features. This is what it means to say that the theory makes a prediction: if that prediction is wrong, the theory itself is wrong.

Much more remains to be said about the notion of “possible rule” in phonology; nevertheless, we can see that distinctive feature theory plays a vital role in delimiting possible rules, especially in terms of characterizing the classes of segments that can function together for a rule. We now turn to a discussion of rule formalism, in the light of distinctive feature theory.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)