النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

DNA Is a Double Helix

المؤلف:

JOCELYN E. KREBS, ELLIOTT S. GOLDSTEIN and STEPHEN T. KILPATRICK

المصدر:

LEWIN’S GENES XII

الجزء والصفحة:

25-2-2021

2818

DNA Is a Double Helix

KEY CONCEPTS

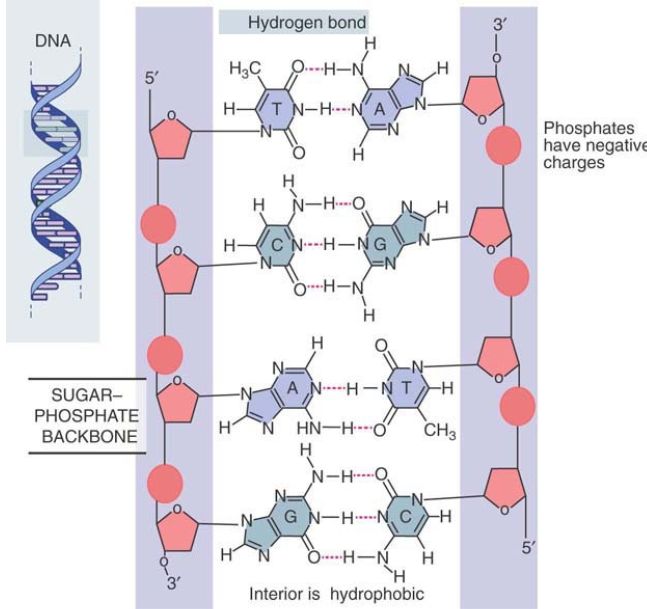

- The B-form of DNA is a double helix consisting of two polynucleotide chains that are antiparallel.

- The nitrogenous bases of each chain are flat purine or pyrimidine rings that face inward and pair with one another by hydrogen bonding to form only A-T or G-C pairs.

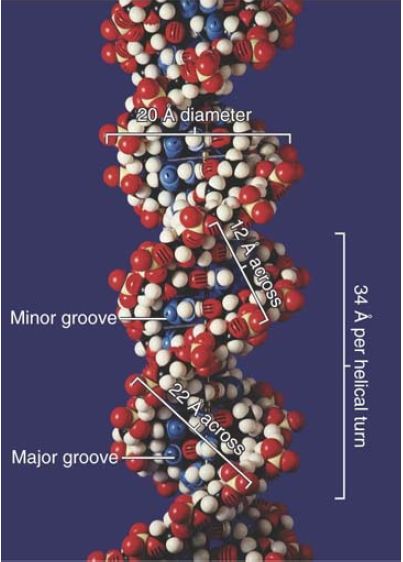

- The diameter of the double helix is 20 Å, and there is a complete turn every 34 Å, with 10 base pairs per turn (about 10.4 base pairs per turn in solution).

- The double helix has a major (wide) groove and a minor (narrow) groove.

By the 1950s, the observation by Erwin Chargaff that the bases are present in different amounts in the DNAs of different species led to the concept that the sequence of bases is the form in which genetic information is carried. Given this concept, there were two remaining challenges: working out the structure of DNA, and explaining how a sequence of bases in DNA could determine the sequence of amino acids in a protein.

Three pieces of evidence contributed to the construction of the double-helix model for DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953:

- X-ray diffraction data collected by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins showed that the B-form of DNA (which is more hydrated than the A-form) is a regular helix, making a complete turn every 34 Å (3.4 nm), with a diameter of about 20 Å (2 nm). The distance between adjacent nucleotides is 3.4 Å (0.34 nm); thus, there must be 10 nucleotides per turn. (In aqueous solution, the structure averages 10.4 nucleotides per turn.)

- The density of DNA suggests that the helix must contain two polynucleotide chains. The constant diameter of the helix can be explained if the bases in each chain face inward and are restricted so that a purine is always paired with a pyrimidine, avoiding partnerships of purine–purine (which would be too wide) or pyrimidine–pyrimidine (which would be too narrow).

- Chargaff also observed that regardless of the absolute amounts of each base, the proportion of G is always the same as the proportion of C in DNA, and the proportion of A is always the same as that of T. Consequently, the composition of any DNA can be described by its G-C content, or the sum of the proportions of G and C bases. (The proportions of A and T bases can be determined by subtracting the G-C content from 1.) G-C content ranges from 0.26 to 0.74 among different species.

Watson and Crick proposed that the two polynucleotide chains in the double helix associate by hydrogen bonding between the nitrogenous bases. Normally, G can hydrogen-bond most stably

with C, whereas A can bond most stably with T. This hydrogen bonding between bases is described as base pairing, and the paired bases (G forming three hydrogen bonds with C, or A forming two hydrogen bonds with T) are said to be complementary. Complementary base pairing occurs because of complementary shapes of the bases at the interfaces where they pair, along with the location of just the right functional groups in just the right geometry along those interfaces so that hydrogen bonds can form.

The Watson–Crick model has the two polynucleotide chains running in opposite directions, so they are said to be antiparallel, as illustrated in FIGURE 1. Looking in one direction along the helix, one strand runs in the 5′ to 3′ direction, whereas its complement runs 3′ to 5′.

FIGURE 1. The double helix maintains a constant width because purines always face pyrimidines in the complementary A-T and G-C base pairs. The sequence in the figure is T-A, C-G, A-T, G-C.

The sugar–phosphate backbones are on the outside of the double helix and carry negative charges on the phosphate groups. When DNA is in solution in vitro, the charges are neutralized by the binding of metal ions, typically Na+ . In the cell, positively charged proteins provide some of the neutralizing force. These proteins play important roles in determining the organization of DNA in the cell.

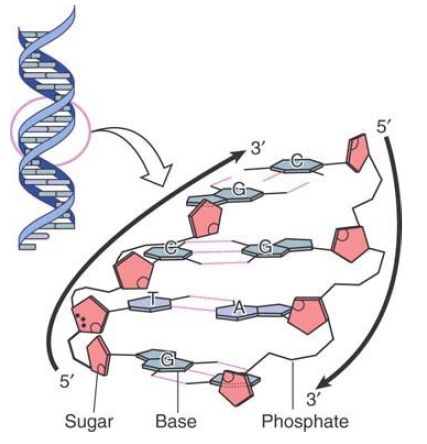

The base pairs are on the inside of the double helix. They are flat and lie perpendicular to the axis of the helix. Using the analogy of the double helix as a spiral staircase, the base pairs form the steps, as illustrated schematically in FIGURE 2. Proceeding up the helix, bases are stacked on one another like a pile of plates.

FIGURE 2. Flat base pairs lie perpendicular to the sugar–phosphate backbone.

Each base pair is rotated about 36° around the axis of the helix relative to the next base pair, so approximately 10 base pairs make a complete turn of 360°. The twisting of the two strands around each other forms a double helix with a minor groove that is about 12 Å (1.2 nm) across and a major groove that is about 22 Å (2.2 nm) across, as can be seen from the scale model presented in FIGURE 1.14. In B-DNA, the double helix is said to be “righthanded”; the turns run clockwise as viewed along the helical axis.

(The A-form of DNA, observed when DNA is dehydrated, is also a right-handed helix and is shorter and thicker than the B-form. A third DNA structure, Z-DNA (named for the “zig-zag” pattern of the backbone), is longer and narrower than the B-form and is a lefthanded helix.

FIGURE 1.14 The two strands of DNA form a double helix. © Photodisc.

It is important to realize that the Watson–Crick model of the B-form represents an average structure and that there can be local variations in the precise structure. If DNA has more base pairs per turn, it is said to be overwound; if it has fewer base pairs per turn, it is underwound. The degree of local winding can be affected by the overall conformation of the DNA double helix or by the binding of proteins to specific sites on the DNA.

Another structural variant is bent DNA. A series of 8 to 10 adenine residues on one strand can result in intrinsic bending of the double helix. This structure allows tighter packing with consequences for nucleosome assembly and gene regulation.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)